István Szabó: Mephisto, Colonel Redl (Redl ezredes), Hanussen

István Szabó’s three films made with the actor Klaus Maria Brandauer, the Oscar-winning MEPHISTO, COLONEL REDL and HANUSSEN, are released on Blu-ray as a box set by Second Run. Reviewed by Gary Couzens.

Our view of another country’s cinema is frequently not the same as that of those who live in that country. That’s especially so where the country’s language is other than English, as what is shown in British arthouses with subtitles is not what the majority of filmmakers there go to see in their own language. By 1980, István Szabó (born 1938) had directed seven feature films, of which just two – Father (Apa, 1966) and Confidence (Bizalom, 1980) – had had UK cinema releases. Other than that, Father had had a television showing on BBC2 in 1972 and Szabó’s debut feature Age of Illusions (Álmodozások kora, 1965), had had its British premiere on the same channel in 1967 as The Age of Daydreaming. So, respectable enough in arthouse terms. However, as so often, it takes the success of one film for someone to to break through and for Szabó that was Mephisto, which premiered in its coproduction countries of Hungary and West Germany in February and April 1981 respectively, played in competition at Cannes that year and reached British cinemas in November. It became the first Hungarian film to win the Oscar for Best Foreign-Language film and remains the only one other than Son of Saul in 2016.

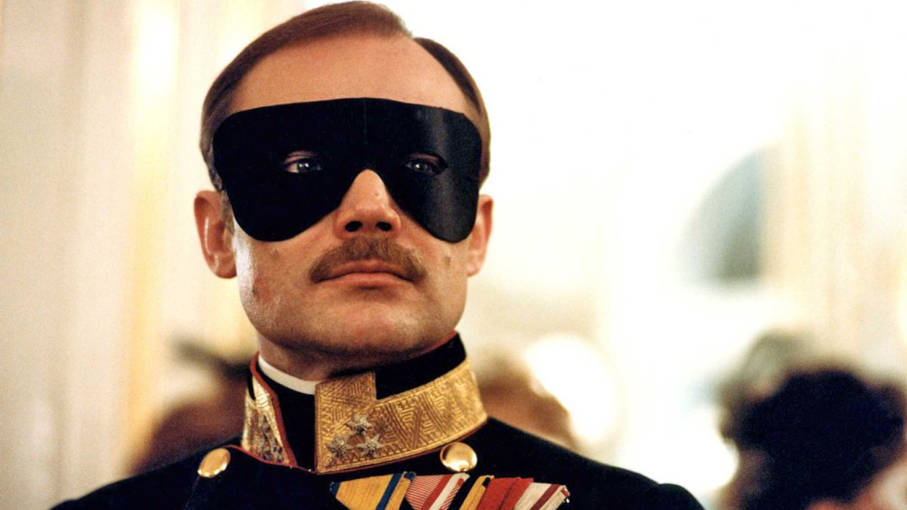

Part of the impact of the film was due to the lead performance by Austrian actor Klaus Maria Brandauer and he and Szabó worked together two more times, in the films included in this Blu-ray box set. All three films centre on Brandauer’s commanding performances and deal with aspects of twentieth-century history, especially the rise of Nazism and an individual’s response to it. Brandauer was thirty-seven when he made Mephisto. While he had acted in films before (including his English-language debut in The Salzburg Connection in 1972), he was primarily then a stage actor. However, Mephisto attracted the interest of American studios and soon he was working in the States, as a Bond villain in Never Say Never Again (1983) and as Baron Blixen in Out of Africa (1985), for which he won a Golden Globe and was Oscar-nominated as Best Supporting Actor. So, while he continues to act, his profile outside Europe is not what it was, with few of his films post 1990 being seen in the UK and USA. For much of the 1980s he could claim to be one of the foremost screen actors of his time. This box set is a reminder of that.

MEPHISTO

Germany, the 1920s. Hendrik Höfgen (Brandauer) is an actor, struggling in provincial theatres but with ambitions to greater things. He meets Barbara Bruckner (Krystyna Janda), the daughter of a professor, and courts her in an attempt to improve his position. His performance as Mephisto in a production of Goethe’s Faust impresses a general (Rolf Hoppe). Meanwhile, following the Reichstag Fire in 1933, the Nazis have taken power. Although Barbara has left Germany with her Jewish father, Höfgen elects to stay behind, having to accommodate the ruling régime…

Mephisto is fiction, but it is inspired by fact, that of the actor Gustav Gründgens, whose Mephisto in Faust was one of his signature roles. In its tracing of the rise of Höfgen, Szabó’s film (co-written with his regular screenwriting partner Péter Dobai, from the 1936 novel by Klaus Mann, son of Thomas) is the study of a man who is not a villian but who opportunistically tries to succeed, which leads him to collaborate with the forces overtaking his country. Given that Hungary was a Communist state at the time, you have to wonder how much the film’s examination of being an artist in a totalitarian state resonated for Szabó, his crew and much of his cast.

The film is a lengthy one, just under two and a half hours, but Szabó keeps it going at a good clip. Cinematography and production design are well-appointed. However, what holds the film together is the enough-guns-to-sink-a-battleship performance from Brandauer, whom Szabó had seen on stage in Vienna. This is such a commanding performance that it’s easy to forget that some of the other actors, some of them quite distinguished, are even in the film. Rolf Hoppe holds his own as the Nazi general on whose favour Höfgen depends, but third-billed Krystyna Janda, who by then had made a strong impression in Andrzej Wajda’s films – and who was about to deliver probably her finest performance in Interrogation (Przesłuchanie, made in 1982 but banned in Poland until 1989) – is frankly overshadowed.

Between 1967 and 1992, seven of Szabó’s films have been submitted as the Hungarian entry for the Oscar for the Best Foreign-Language film (now Best International Feature Film), more than by any other director from the country. Mephisto was his first to reach nomination stage and, as mentioned above, was shortlisted and won, beating amongst others Wajda’s Man of Iron (Człowiek z żelaza) and Francesco Rosi’s Three Brothers (Tre fratelli). That was its only Oscar nomination, as Brandauer was clearly overlooked as Best Actor. (Henry Fonda won that year for On Golden Pond, but that was a clearly sentimental decision which I doubt posterity has endorsed.) Brandauer did receive a BAFTA nomination for Most Outstanding Newcomer to Leading Film Roles, losing to Joe Pesci in Raging Bull. The film did win the FIPRESCI Prize and the Best Screenplay award at Cannes, though the Palme d’Or went to Man of Iron.

COLONEL REDL

In the 1880s, Alfred Redl (Brandauer) earns a place at the royal military academy due to his loyalty to the Austria-Hungarian empire. There he befriends a fellow cadet, Christoph Kubinyi (Jan Niklas), defending him when he kills another cadet in a Jew. The dead man was Jewish, and Redl hides his own Jewishness. He also hides his homosexual inclinations (while still carrying on affairs with women, including Kubinyi’s sister Katalin (Gudrun Landgrebe)) and as he advances up the ranks and in society, this leads to his downfall.

Colonel Redl (Redl ezredes in Hungarian, Oberst Redl in German) is based on a true story, that of the real Alfred Redl (1864-1913). However it is largely fictionalised and is “inspired” as the credits say by John Osborne’s play A Patriot for Me. Osborne (1929-1994) will forever be known for his third play Look Back in Anger (1956), which kickstarted a theatrical movement, favouring younger, regional voices and a backlash against the “well-made plays” which were prevalent on British stages at the time. As such, Osborne and his colleagues became known as Angry Young Men – and they were almost all men, Shelagh Delaney and Ann Jellicoe apart. Osborne had an impact on British cinema, founding Woodfall Productions with Tony Richardson (who had directed the original production of Anger on stage) and Harry Saltzman. Woodfall’s first two films were derived from Osborne’s plays: Look Back in Anger in 1959 and The Entertainer (preserving one of Laurence Olivier’s major stage roles) in 1960. This put Woodfall at the forefront of a new wave in British cinema. Although Osborne’s involvement with the company had ceased by then, another film they made from one of his plays was Inadmissible Evidence (1968), also carrying over the original stage lead actor to the big screen, in this case Nicol Williamson. In amongst these and other works, Osborne wrote A Patriot for Me in 1965. This had to be performed under private membership club conditions as the Lord Chamberlain refused a licence due to the play’s homosexual themes and content. The play has a large cast, which has meant that it, to some people Osborne’s best work for the stage, is rarely revived. A very theatrical play – with a scene of a drag ball regarded as a stage tour de force – becomes inevitably a more realistic film, with the same high production values, from the same principal crew members, as Mephisto four years earlier.

In contrast to his heightened performance in Mephisto – kept just this side of showboating – Brandauer is tamped down, in keeping with his repressed, indeed closeted character. So the film has a long build-up (like Mephisto it comes in just under two and a half hours) to an undeniably powerful climax. As with Mephisto, the personal story is counterpointed with the historical events going on in the background in what was then Austria-Hungary, which led to (as in the final sequence) the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (Armin Mueller-Stahl) and the outbreak of World War One. The real Redl was homosexual, but was a spy for the then Russian Empire and subject to blackmail.

As with Mephisto, Colonel Redl was Oscar-nominated for Best Foreign-Language Film, but lost to the Argentinian The Official Story (La historia oficial, also known in English as The Official Version). It did however win the BAFTA in the same category and the Jury Prize at Cannes, but again Brandauer was overlooked for all three awards.

HANUSSEN

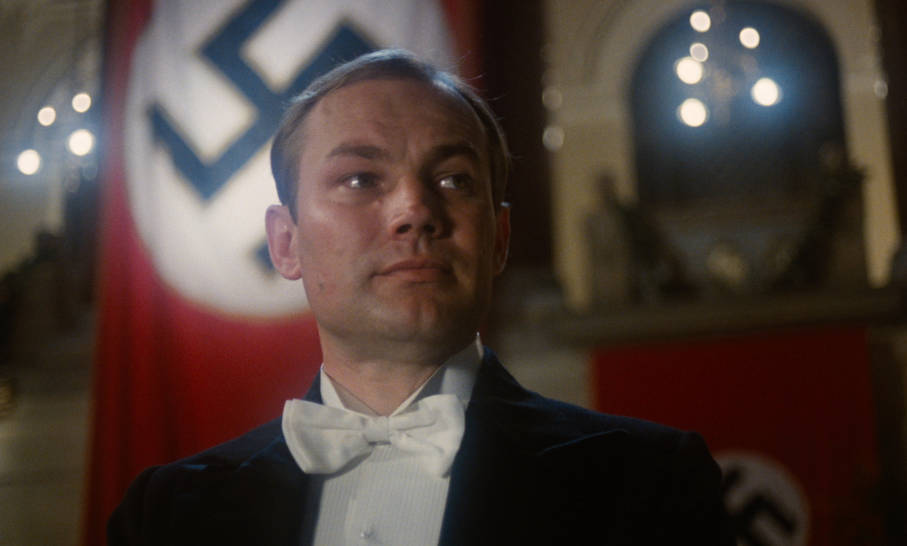

Towards the end of World War I, Austrian corporal Klaus Schneider (Brandauer) is shot in the head. He recovers in hospital under Doctor Bettelheim (Erland Josephson). Whether as a cause of the injury, or an inbuilt talent which has just come to the fore, Schneider begins to have premonitions. After leaving hospital, after the end of the war, Schneider’s powers of hypnosis and clairvoyancy finds him in demand, first at dinner parties. Then he goes on stage, adopting the name of Erik-Jan Hanussen. As his fame spreads, he comes to the attention of the German authorities…

Hanussen, released in 1988, was Szabó’s third feature film in a row to star Brandauer, and preceded his move into more international film work (outside Hungary and West Germany, that is) with Meeting Venus in 1991. Again it is based on fact, specifically its central character’s autobiography, again with a script by Szabó and Dobai. (Paul Hengge is credited with additional material and Gabriella Prekop with dialogue.) We also counterpoint Schneider/Hanussen’s story with twentieth-century events, beginning in the First World War and culminating in the Reichstag Fire which he has foreseen. While the film doesn’t confirm that its protagonist is genuinely psychic and gifted with premonitory visions, it doesn’t deny it either, placing it on the dividing line between a realistic historically-set drama and fantasy, and the tension between the two works to its benefit. Again, the theme is that of the relationship between an artist (a clairvoyant rather than an actor this time) and a totalitarian state, which leads to man’s rise and eventual downfall. Some characters are clearly fictionalised, such as photographer, film director and aficionado of Aryan male and female beauty (especially of the unclothed variety) Henni Stahl (Ewa Błaszczyk), a thinly-disguised Leni Riefenstahl, who was still alive at the time the film was made.

Brandauer’s performance is pitched somewhere between those in the two other films of this set, and there is strong work from in particular Erland Josephson as the doctor who treats him and Ildikó Bánsági (who had played Nicoletta von Niebuhr in Mephisto), Grażyna Szapalowska and Adrianna Biedrzyńska as the various women in his life. Hanussen is a shorter film that its predecessors, at just under two hours rather than just under two and a half (though see below under “Sound and Vision”) and benefits from being so. This was Szabó and Brandauer’s final collaboration. It was received with a little disappointment at the time, one shared by its director, but viewing it thirty-six years after its original British release reveals that it’s on a par with them. It premiered in competition at the 1988 Cannes Film Festival, but came away without a prize.

sound and vision

Mephisto, Colonel Redl and Hanussen are released on Blu-ray by Second Run, the discs encoded for all regions (ABC). Mephisto had an AA certificate on its original cinema release, the other two films 15, and all three are 15 on these discs. The four short films don’t appear on the BBFC website as I write this, though two of them at least (You and Concert) were in UK 16mm non-theatrical distribution in 1972 – reviewed by the Monthly Film Bulletin in September that year – but without being submitted to the BBFC. Hanussen was actually classified twice for cinema release: at 142 minutes in September 1988 and then at 117 in May 1989. That was after the film was re-edited and shortened, but the latter version is now the official one and is the one restored and on disc in this set. I have only seen this version, so am not aware of what the differences were. These Hungarian/West German coproductions were released with two official versions, in those languages. The versions on these discs are visually the Hungarian ones, with credits in that language, but you have the option of Hungarian or German soundtracks, of which more in a moment.

All three films were shot on colour 35mm film, and the Blu-ray transfers, from restorations supervised by cinematographer Lajos Koltai, are in the intended ratio of 1.66:1. All look fine, with rich colours, solid blacks and filmlike grain. For technical reasons, I have been unable to source screengrabs from the review discs sent, so the images in this review are publicity stills provided by Second Run.

The soundtracks are the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. It’s here that the alternate language versions come into play. These productions follow the common European practice of the cast speaking their native languages on set, dubbed accordingly for particular versions. So the German actors were speaking German, the Hungarians Hungarian, and you can tell this by the lack of lipsynch in the “other” version to those of the actor’s nationality. As to which version you prefer (the German ones were those released in UK cinemas and shown on television), the choice is yours. The German versions do have Brandauer’s voice, which is a consideration given how dominating he is in each film. (His Hungarian voice in all three films is provided by Sándor Szakácsi, who also has another acting role in Colonel Redl.) Some actors are dubbed in both versions, for example Krystyna Janda in Mephisto, Grażyna Szapalowska and Erland Josephson in Hanussen. Presumably they were speaking their native languages too, respectively Polish, Polish and Swedish, but as I can’t speak those languages, let alone lip-read them, that’s subject to confirmation. One exception is David Robinson, who plays a theatre critic for The Times of London (when he was the film critic for that newspaper), who delivers his lines in English and they are heard in that language. English subtitles for the features and the extras are optional, though for some reason they aren’t available for the trailers.

special features

MEPHISTO

Variations on a Theme (Variációk egy témára) (11:17)

This short was made in 1963 for the Béla Bálasz Studio. It is subdivided into three named parts, “Objectively”, “Shock” and “Screaming”. There is no dialogue, but there is some sparse narration, otherwise the soundtrack is devoted mostly to music and some significant sound effects. The first part depends heavily on some quite grainy stock footage all derived from wartime: soldiers smiling, a row of tanks and planes in the air, audiences saluting Hitler. Then the fighting starts, bombs fall, buildings blow up, dead bodies lie on the ground. In the second part (from now on new footage shot in black and white 35mm) a man takes his son around a museum where weapons – guns, grenades – are on display and the man explains how they are used. For the duration, this is silent except for music, then we hear the rattle of machine-gun fire. The third part features some young people, no doubt the hipsters of their day, all wearing dark sunglasses, smoking while a waitress serves them drinks. A saxophonist sits on a wall and plays. Then we hear the sounds of soldier’s marching. Are these people oblivious to what may soon happen? The film craft is obvious, if the theme of this short is a little obscure.

István Szabó: The Director Answers (10:28)

An interview from 2022, featuring clips not only from Mephisto (the film of his he mostly talks about), plus some from his earlier films. Szabó says that as his career has progressed, he has become more interested in dealing with social issues, but does wish to show people more often in their complexity. Regarding Mephisto, he talks about the original novel and his collaborations with his regular writer and cinematographer. Six names were suggested for the lead, and he saw Brandauer on stage in Vienna before casting him.

Trailer (1:59)

A Hungarian-soundtracked trailer, which does not have subtitles available.

Booklet

Second Run’s booklet runs to twenty pages. Other than credits at the end, it comprises an essay on Mephisto by John Cunningham. This also works as an introduction to the whole box set, as it discusses the fact that Szabó does not regard the three films as a trilogy, despite the lead actor in common and the similar themes and historical settings. Cunningham continues with details of European history, which was largely dominated by both Germany and Austria-Hungary at the start of the twentieth century. Culture at the time on the continent was largely Germanic. The past may be a foreign country but, Cunningham says, with these films Szabó and his collaborators allow us to visit it.

Mephisto began when Szabó was sent a copy of the novel in the late 1970s. Gustav Gründgens had in fact not only been known to Klaus Mann, he had been his brother in law for a time. Szabó had wanted to work from an existing literary source for some time, and to work internationally given that his previous features were almost entirely set in Hungary. Cunningham discusses the novel’s controversy (Gründgens’s descendants aiming to prevent publication in West Germany after his death) and its allusions to the Faust legend, with other versions of that story taken into consideration. (One of them was Klaus Mann’s father Thomas’s Doktor Faustus, published 1947.) The novel and film’s view of the story is akin to Christopher Marlowe’s play, with the protagonist’s betrayal of his own soul driven by his own vanity. Cunningham discusses the film’s production and its release. It became Szabó’s biggest hit in his home country and remains so to this day. Cunningham calls it “an undoubted masterpiece”.

COLONEL REDL

From 1963, You was Szabó’s final short made before his first feature, Age of Illusions. Rather noticeably influenced by the French New Wave, this is a study of the face of a young woman (Cecilia Esztergályos) as she asks her offscreen lover about his feelings for her. For him, she represents movement as she is constantly in motion, especially in shots of her in various parts of Budapest, in stop frame, slow and fast motion, in reverse. Ultimately this is Szabó’s showing off his command of technique, but it’s still a fresh piece.

Concert (Koncert) (16:54)

Made in 1961 as Szabó’s diploma film at the Academy of Drama and Film in Budapest, Concert has no dialogue or narration, only music (both diegetic and non-diegetic) and some sound effects. Three young men are transporting a piano along the banks of the Danube in the city. Distracted by a pretty girl, the men leave the piano where it is, and it receives attention from passers-by. They try to play something on it, attempt to protect it when it begins to rain and eventually take it away, only to be chased by the original owners. An engaging and inventive short.

Remembrance of Jósef Romvári (8:10)

A short tribute to production designer and art director Romvári (1926-2011) by his granddaughter Sophy Romvári. István Szabó narrates in English, addressing a woman who replies that she wishes she had met the man, so that’s presumably not the director of this piece. In a career lasting from 1955 to 2004, Romvári worked on some 140 films, including the three in this box set. We see some of his production drawings and extracts from some of those films, including details of the entire house interior he built for Confidence. We end with some video footage of the great man playing with a young girl, who is presumably Sophy herself.

Trailer (2:22)

Again a trailer with no subtitles available, with a Hungarian soundtrack. Plenty of clips from the film, though some are likely spoilery.

Booklet

Also running to twenty pages, this booklet comprises an essay by Peter Hames. He also refers to the three films in the set not being an intended trilogy, but have become one after the fact. Colonel Redl had its source in Szabó and Brandauer wanting to work together again. So they settled on the story of Alfred Redl, which had seen various stage and film versions before John Osborne’s play. The first take on the story from Egon Erwin Kisch, who had apparently uncovered a cache of documents in the 1920s relating to Redl. However, this story appears to have been apocryphal and Kisch uncovered the story in 1913, shortly after Redl’s death. Hames provides a short biography of the real Alfred Redl, Szabó’s film doesn’t set out to provide a factual account, but sees Redl in trying to preserve his position by entering elite society, despite his suppressed homosexuality (which the film doesn’t reveal until some way in) and also his Jewish heritage. Also, the land of his birth (Galicia, now in Ukraine) was frequently disputed between Poland, Russia and Austria-Hungary. His people, the Ruthenians, were looked down upon by other parts of Europe. Hames talks about Szabó’s filmmaking style, in particular his concentration on Redl, often shown in close-up. Hames regards the film as one of the best made about the end of the Habsburg Empire.

HANUSSEN:

City Map (Várostérkép) (16:50)

This short dates from 1977, so Szabó’s directing career was well established by this point, with four features under his belt and the fifth, Budapest Tales (Budapesti mesék), out the same year. So, unlike the three other shorts in this set, this is in colour, though it does include monochrome still photographs and archive material. The credits appear over an old city map, that of Szabó’s native Budapest. After that we take a tour of the city, particular some residential areas outside the centre. It’s a picture of a city whose past lives on in the buildings and the memories of the people, so we see families spending afternoons together, stories of young love – and bombs going off, wrecked houses, tanks going down streets. This lyrical piece won top prize at the International Short Film Festival in Oberhausen in 1977.

István Szabó’s Central Europe (3:07)

This is something of a showreel, likely intended as a tribute, with clips from the director’s films, the three in this set and earlier ones. The extracts appear to be from HD sources, which does make one hope that the earlier films could make their way to Blu-ray in due course. The video footage of Mephisto’s Oscar win is a little rough in comparison. It ends with “Thank you, István Szabó!”

Trailer (2:25)

And again, a trailer which is hard to judge for the non-Magyar-enabled like myself, as no subtitles are available.

Booklet

Again twenty pages, this booklet has not one but two shorter essays. The first, “Hanussen: Hitler’s Clairvoyant” by Stephen Lemons, was first published by salon.com in 2002. This piece is a history of the man himself, with no reference to the film. Hanussen, “Europe’s greatest oracle since Nostradamus”, was either a con man or a genuine psychic. Lemons keeps both interpretations in balance, though suggests that Hanussen’s predictions were more to do with his insight into the ways history was progressing. He might have predicted Hitler’s rise to power and the Reichstag Fire, but he couldn’t see where this was leading for himself. The second essay, “István Szabó’ Hanussen” by Catherine Portuges, as its title suggests complements Lemons’s piece by concentrating on the film, Szabó’s third “Story of Central Europe”. Colonel Redl is Szabó’s favourite of his own films, along with Father, and he regarded Hanussen as something of a failure, its first half being acceptable, its second not. Portuges points out that the real Hanussen was Jewish, but this is something Szabó removed from his film. She discusses the varying approaches of the three films, with Hanussen an individual who believes he can benefit humanity by being an individual. However he is wrong. Portuges ends with an account of something very recent: October 2025, with Szabó being honoured at the Lumière Festival in Lyon, with a plaque unveiled on the Filmmakers’ Wall, on the site of the Lumière Brothers’ first ever film location in 1895.

A general note on all three booklets: while the essays’ value is obvious, it would have been good to have something other than credits for the extras. That’s particularly so with the short films, some of which would benefit from some contextualisation.

final thoughts

While they were not intended as a trilogy, these three films became one as a default, with their shared themes and historical settings and three commanding performances by Klaus Maria Brandauer. He became a leading actor of the decade and István Szabó became a leading director in Europe and beyond. Some four decades later, the films are still current even though both men’s fame has waned somewhat. Second Run’s box set presents the films well, and Szabó’s short films are a particular bonus.

István Szabó: Mephisto, Colonel Redl (Redl ezredes), Hanussen

Mephisto

Hungary / West Germany / Austria 1981 | 146 mins

directed by: István Szabó

written by: Péter Dobai, István Szabó; from the novel by Klaus Mann

cast: Klaus Maria Brandauer, Ildikó Bánsági, Krystyna Janda, Rolf Hoppe, György Cserhalmi

Hungary / West Germany / Austria 1985 | 144 mins

directed by: István Szabó

written by: István Szabó, Péter Dobai; inspired by the play A Patriot for Me by John Osborne

cast: Klaus Maria Brandauer, Hans-Christian Blech, Armin Müller-Stahl, Gudrun Landgrebe

Hungary / West Germany / Austria 1989 | 140 mins

directed by: István Szabó

written by: Péter Dobai, István Szabó, Gabriella Prekop (dialogue), Paul Hengge (additional material); from the autobiography by Erik Jan Hanussen

cast: Klaus Maria Brandauer, Erland Josephson, Ildikó Bánsági, Walter Schmidinger

distributor: Second Run

release date: 8 December 2025