Short Sharp Shocks Volume 4

The BFI’s fourth compilation of SHORT SHARP SHOCKS short films, from nearly-features to less than a minute, is released on Blu-ray. Review by Gary Couzens.

This is the fourth compilation of short films that the BFI have put out under the title Short Sharp Shocks in its Flipside line, two years after the third. The first, released in 2020, predates my time on this site, but you can find my reviews of Volume Two and Three here. For the fourth volume, the number of films over the two disc has increased to twelve from ten and are a mix of professional productions which you may have seen in cinema supporting programmes to amateur productions (in 8mm or 16mm), to public information pieces which scarred many for life at a young age, and some which originally saw the light of day, or rather the light of a cathode-ray tube, on television. The longest in this set counts as a feature by some definitions (such as the forty-five minutes the Internet Movie Database uses) while the shortest is just over a minute. What would have formed part of the full supporting programme of old is now the main event. Are you sitting comfortably?

THE FATAL NIGHT

At fifty minutes, The Fatal Night, released in 1948, is the kind of mid-length film – a three-reeler in old money – that you made it to the cinema in time for, or stayed behind for after the end credits of the main feature, the one you had actually paid your shillings to see, had finished. Such films continued in British cinemas for decades more: see for example the Flipside release The Orchard End Murder, which stuck in the minds of those who came along for its X-certificate running mate Dead and Buried. Written by Gerald Butler, based on an adaptation of Michael Arlen’s short story “The Gentleman from America”, and directed by Mario Zampi, The Fatal Night probably goes as far as a British horror film could go at the time, especially as local horror production had pretty much ended during World War II.

Mario Zampi was a man with many interests in the film industry, as a producer, and studio co-founder (Two Cities Films, which made such prestigious work as David Lean and Noel Coward’s first films and Laurence Olivier’s Henry V and Hamlet). As a director, Zampi was best known for comedies such as Laughter in Paradise (1951) and The Naked Truth (1957), which makes The Fatal Night all the more surprising, though it is not devoid of humour. Puce (Lester Ferguson) accepts a bet from his friends Cyril (Leslie Armstrong) and Tony (Patrick Macnee) to spend a night in a supposedly haunted house. He is left with a loaded revolver and a candle with one match. He also finds a novel which he reads while the candlelight lasts. This takes us into a story within the story, featuring Victorian sisters Geraldine (Jean Short) and Julia (Brenda Hogan), and how this ties in to the main story I’ll leave you to find out. The results are often tense. News reports of the time suggest that the film had to be toned down at the behest of the British Board of Film Censors (BBFC) who may have threatened the film with a H certificate (for “horrific”, not “horror” as popularly supposed as not all films given that rating were horror films), which would have restricted audiences to the over-sixteens. This may have happened at script stage or in production, as The Fatal Night is on record at the BBFC as having been passed uncut with an A. This allowed accompanied children, but the Monthly Film Bulletin in May 1948 thought the end result was “most definitely not a film to be seen by the very nervous or by juvenile audiences”. When it was on release some critics urged you to make sure you saw it. Many listings I’ve found suggest it often accompanied the really rather different The Bishop’s Wife.

Shot in black and white Academy Ratio, this is transferred to Blu-ray via a 2K scan of an original duplicating positive. It is in the intended aspect ratio of 1.37:1.

DEATH IN THE HAND

While slightly shorter (forty-three minutes instead of fifty), Death in the Hand has structural similarities to The Fatal Night and was released in the same year, 1948. It has a frame story bookending a central flashback and an epilogue of some ten minutes after the story reaches its climax. In a hotel, regular visitor and palmistry expert Cosmo Vaughan (Esme Percy) tells a father and daughter about a fatal train journey he took with four other passengers in the same carriage (John Le Mesurier among them). Each of the passengers have their life lines crossed by another line, indicating severe injury or death at a certain age, the age they are now…

If structurally this film, written by Douglas Clevedon (“a variation on a theme by Sir Max Beerbohm”, as the opening credits, partly spoken as well as written, put it) and directed by A. Barr-Smith, has a passing resemblance to The Fatal Night, it’s not as well-achieved, The frame/prologue, epilogue and frame closure are over-extended, and tending to distract from the taut middle section. The finale of that section, despite obvious model trains and stock footage, is well-achieved. Australian-born producer/director A. Barr-Smith only directed one other film, the feature The Hangman Waits, a year earlier. The story has its origin in a story by Beerbohm, which had been adapted for radio in 1939, with Esme Percy again in the lead role. He dominates the film with his scenery-chewing, but as well as Le Mesurier one of the supporting cast who was later much better known was Shelagh Fraser as the daughter in the frame story. Aged twenty-seven here, she would just over two decades later play the mother of A Family at War on the small screen. Death in the Hand was released in March 1948, playing in support to the similarly A-certificate spy thriller Against the Wind.

Death in the Hand was shot in black and white Academy Ratio. The transfer is from a 2K scan of the original 35mm negative. There’s very little damage, only some speckles and scratches where you’d normally see them on a film element, at the beginnings and ends of reels (of which there are four). Cue dots also appear in the appropriate places, but that’s a feature of a 35mm print, not a bug.

STRANGE EXPERIENCES: HALLOWEEN PARTY / STRANGE EXPERIENCES: THE LAUGHING CLOWN

Strange Experiences was a series shown in the early days of ITV, which launched in September 1955. At that point there was no ITV network yet, and until February 1956 there was just the one region, covering London and the South-East. This was split between two franchise holders, Associated-Rediffusion (later simply Rediffusion) on weekdays and ATV at the weekends. Strange Experiences was a schedule-filler for ATV, broadcast on Sunday evenings at 7.10pm, starting on its opening night of 24 September. Each macabre tale was between three and three and a half minutes long (in a five-minute slot with commercials) and was narrated by Peter Williams, with the actors uncredited. They were clearly done on a tiny budget, with few exteriors that weren’t stock footage. As they were shot on film rather than broadcast live, they survive in the archive. Two of them were on Short Sharp Shocks Volume Three and now we have two more.

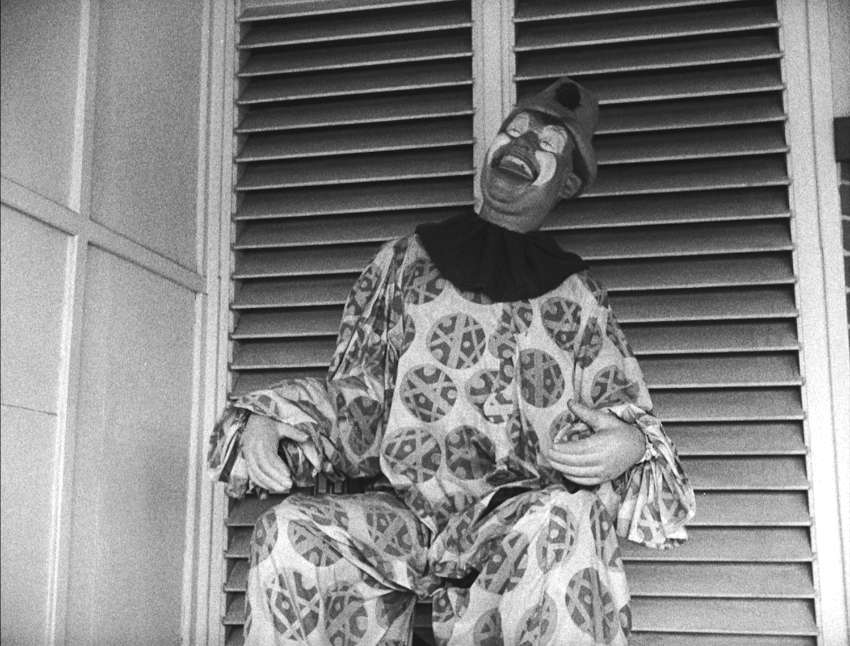

Halloween Party (broadcast on 29 October, appropriately enough) begins as close to a drawing-room comedy as you can get. A woman (Elspet Gray) tells a young man (Ian Whittaker) of a superstition. If he throws an apple peel over his shoulder when it lands on the floor it should form a letter which is the initial of the woman he will marry. But will he get what he bargained for? In The Laughing Clown (19 February 1956) Peter Williams takes centre stage in a story which is almost entirely narrated story other than the chilling laughter of the rather impressive mechanical clown of the title. Its origins – and those of its laughter – we soon find out.

Both shot on 35mm film in black and white, these two shorts are transferred from a 2K scan from 35mm duplicating positives, in the ratio of 1.33:1.

NIGHT RIDE

Denis Meikle (1947-2022) went on to become a prominent film historian, particularly of classic horror films, but in the mid 1960s clearly harboured filmmaking ambitions, making several shorts with an 8mm camera and with himself and friends in the cast. Night Ride, from 1967, is one of those. Two men (James Whitehead and Meikle) and a “girl” as the credits put it (Virginia McNally) call at an isolated house with a plan to rob the place, but the occultist owner (John Attfield) has other ideas. While the production shortcomings are obvious, from the huge changes in ambience every time it switches from music-only to synch-sound to the wobbly acting and the rather muddled storyline, but so is the ambition. At one point, a narrator cuts in to advise that “people of a nervous disposition should turn away now”.

Shot in Super 8mm on colour reversal stock, Night Ride is transferred via a 2K scan of the original element. The sound is restored from the original magnetic stripe. The source has all sorts of shortcomings, especially given the sub-standard gauge, with scratches and splices. A good few lens flares are no doubt baked in from the film’s original production. The aspect ratio is 1.33:1.

MIRROR MIRROR

Made in 1969 by the Eastbourne Cine Group, which means that the exteriors are now a time capsule of that town as it was fifty-five years ago, Mirror Mirror is a short piece involving a mirror that reveals a secret. It’s a film which is again commendably ambitious given its clear limitations. As William Fowler’s piece in the booklet points out, many leading British directors started out making amateur films, such as Peter Watkins and Ken Russell in the late 1950s to the more recent Shane Meadows. Director Garry Parsons does not appear to be one of them, but the Eastbourne Club was certainly quite active around the time.

Mirror Mirror was shot in 16mm, and the transfer derives from a 2K scan of the original colour reversal element, in the ratio of 1.33:1. As you’d expect from the gauge, it’s certainly soft and grainy but is in generally good shape.

That’s it for Disc One. Disc Two begins with…

SCARECROW

Scarecrow was made in Ireland in 1972, with money from the BFI Production Board. It is set in that country in 1931 at a time of drought and famine, affecting the livelihood of a farmer (Don Blackwell) and his wife (Dara Merry). There is an opening caption, but no spoken dialogue, so the soundtrack does a lot of the heavy lifting, especially when crows attack. As this was a tiny-budget film that soundtrack is mono, though you can imagine what this might have sounded like if the makers were able to have a stereo mix. William Fowler in his booklet notes makes a comparison with Wake in Fright, though given the lack of dialogue, Night of Fear (1972) is at least as apt an example from Australia. Scarecrow is a film more of mood and disturbing atmosphere rather than a taut narrative, but as such it works.

The booklet says that the transfer was of a 2K scan of the original 35mm negative. However, the BFI’s Collections Database advises that the negatives held are 16mm and all film materials held are in that gauge. It certainly looks like 16mm to me: the darkly-lit opening shot is intensely grainy. The aspect ratio is 1.33:1.

RED

Written and directed by Astrid Frank, who also acts in the film as the serving girl, Red could have been a latterday Hammer production, though at just twenty-four minutes (two reels) it was simply a curtain-raiser for further horrors in store in the main feature. We’re in an unspecified historical period, with a painter (Ferdy Mayne) spending the night in a hostelry. He’s joined by three troubadours (Gabrielle Drake, Mark Wynter, Steve Brownelow) and that evening he witnesses them carrying out an erotic, orgiastic and finally gruesome ritual. Strongish stuff for the time, Red earned itself an X certificate (uncut, though Frank claims the BBFC came close to banning it – see her interview below) which obviously restricted the films it could be shown with. It appears to have been shown with a few different ones from its making in 1976 to the end of the decade, and locally to me played in support to Damien Omen II in 1979. Frank, who before this had been a model and actress, in her native Germany and France as well as the UK, followed this with one other short, The Jealous Mirror, which had a much more family-friendly A certificate and accompanied WarGames in British cinemas in 1983. Hopefully it can be included in a future set.

Shot in 35mm colour (photographed by Robert Krasker, who had won an Oscar for The Third Man), Red is transferred via a 2K scan from a 35mm positive in the ratio of 1.85:1.

SANCTUM

Directed by Bill Davison in 1976, Sanctum is a no-dialogue (indeed, no-soundtrack, but see below) film inspired by Ken Russell’s work, featuring an almost solo performance from Pete Steggall, who is naked throughout, at times full-frontal. It’s a study of disturbance and persecution, featuring a lot of religious imagery, including implied unauthorised use of a statuette of the Virgin Mary. It’s the latter aspect which likely caused the controversy it faced, particularly when it won the Daily Mail trophy awarded by the Institute of Amateur Cinematographers. Despite the prize, the IEC declined to show the film at its awards ceremony. Davison was not a stranger to flak from censorious types: in his booklet piece, he mentions that his earlier film Zenith (1974), a study of a paedophile, faced calls for it to be withdrawn from public screenings. With some justification, he says that 1970s filmmakers often pushed back against the censorship advocated by the likes of Mary Whitehouse, but rather undoes his own argument by comparing this with today’s “woke censorship”. While Sanctum would undoubtedly have been given an X certificate at the time and may have faced problems due to blasphemy laws then on the statute books (caveat: I am not a lawyer), nowadays it is not only passed uncut but at 15 as well and I suspect will pass unnoticed outside the audience for a Blu-ray release like this.

Sanctum was shot on 8mm colour reversal stock, scanned at 2K resolution, presented in the ratio of 1.37:1. It is accompanied by a newly-recorded score by The Begotten in LPCM 2.0, playing in surround.

PLAY SAFE: FRISBEE / PLAY SAFE: ELECTRICITY

While separately billed, these two are really one item, the one-minute Frisbee being just part of the eleven-minute Electricity. Both directed by David Eady, these were made for The Electricity Council to promote safety around their pylons and substations. In the shorter film, a brother and sister are playing with a frisbee near a substation. The toy flies over the fence and the boy squeezes through the railings to retrieve it. Thirty-three thousand volts later, this leaves you with a blood-curdling scream. In the longer version, the dramatised scenes are interspersed with animated sequences featuring a wise old owl (voiced by Brian Wilde) imparting a few lessons to a robin (Bernard Cribbins) with a view to his surviving until adulthood.

Both films were shot in 35mm, and are transferred via 2K scans of the 35mm interpositives in a ratio of 1.37:1.

BLACK ANGEL

In the Middle Ages, Sir Maddox (Tony Vogel) returns home to news of sickness in the land. He sets out to free a woman imprisoned by the Black Angel of the title.

Black Angel had no doubt the highest-profile cinema release of anything in this set, as it was picked by George Lucas to be shown with The Empire Strikes Back. Lucas had apparently been dissatisfied with the short films that had played with Star Wars. That explains the luxury (for a low-budget short) of widescreen and a stereo soundtrack, some of the stock being short ends left over from the Empire shoot. Christian had worked as an art director beforehand, and it was a meeting with 20th Century Fox UK head Sanford Lieberson on the set of Alien which led to his submitting the script for Black Angel to Fox and George Lucas. Beautifully shot by Roger Pratt (who went on to Brazil, Mona Lisa and Mike Leigh’s High Hopes and others), it has atmosphere in spades, leading to a swordfight which is vigorously filmed if kept within family-friendly bounds.

Black Angel was shot in 35mm Scope with anamorphic Panavision lenses. The remaster was done by Roger Christian and is presented in its original ratio of 2.39:1. The stereo soundtrack is rendered in LPCM 2.0, but there is the option to play it in DTS-HD MA 5.1, via the AUDIO button on your remote rather than via the menu. 2.0 is more accurate a rendering than 5.1 for a stereo soundtrack of 1980 (unless, like The Empire Strikes Back, the film was shown in some cinemas in a 70mm blow-up, but there’s no evidence that that happened.) The surrounds are generally used for Trevor Jones’s score and some sound effects like waterfalls and thunderclaps. Both are much the same, other than the 2.0 being mixed slightly louder, so the choice is yours.

sound and vision

Short Sharp Shocks Volume 4 is BFI Flipside release number 52, a two-disc Blu-ray release from the BFI, both discs encoded for Region B only. The set has an 18 certificate. Four of the films were passed by the BBFC for their original cinema releases: The Fatal Night, Death in the Hand, Red and Black Angel which were A, A, X and U respectively and are now all PG except for Red which is 18. The other films are all classified for the first time: Strange Experiences: Halloween Party at U, Strange Experiences: The Laughing Clown at PG, Night Ride 15, Mirror Mirror 12, Scarecrow and Sanctum both 15. The two Play Safes are documentaries so have been exempted from certification, but neither would be passed higher than PG, unsurprising given their intended audience.

The films are transferred with two exceptions in the aspect ratio of 1.37:1 (cinema, the old Academy ratio) or 1.33:1 (television or non-theatrical) and were originated in 35mm, 16mm or 8mm. To avoid too much clutter here, I’ve given details of the transfers with each film above. For technical reasons, I have been unable to source screengrabs from the discs, so this review is illustrated by BFI publicity stills.

The soundtracks are all, with two exceptions, mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0. For Sanctum, there is no original soundtrack as the film was shot mute, so a new score has been provided by The Begotten (a four-piece using voices, guitars and electronics), which is one to wake the neighbours with. As mentioned above, although there’s no Dolby Stereo logo in the end credits, Black Angel did have a stereo soundtrack which could be heard mostly in showcase cinemas in 1980. It’s available on this disc in both LPCM 2.0 (surround) and DTS-HD MA 5.1.

Subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available for the films, though not the extras. They are accurate though I did spot one typo: in Death in the Hand, the town in Kent is Tunbridge Wells, not “Tonbridge Wells”.

special features

It Happened That Night (10:15)

This is an interview with Mario Zampi Jr, the son of the director of The Fatal Night. Mario Jr spent some time on sets while his father was filming. Zampi Sr had been interned on the Isle of Man during the War, but made up for good time. He was clearly a workaholic, a smoker of sixty to seventy cigarettes a day, and his office on Wardour Street was above an Italian restaurant he also owned. (A Pizza Express is now on that site.) Mario Jr says that of his father’s films, The Fatal Night is the one he hadn’t seen before being approached to contribute to this release.

The Devil Upstairs (17:02)

John Attfield, who played the occultist in Night Ride, talks about his longtime friend Denis Meikle, whom he met at school around 1963. Meikle wasn’t the most dedicated of schoolboys, drawing cartoons in his exercise book. They both had filmmaking ambitions, with Attfield writing screenplays, his tastes running more towards comedy than horror. He was and clearly is impressed by his late friend’s filmmaking abilities and his particularly expressive face.

Night Ride: Behind the Scenes

This item leads to a two-part submenu, with behind-the-scenes footage (3:06) and out-takes (1:15). Interesting that these survive, but really one-watch items.

The Colour of Blood (18:19)

Astrid Frank takes centre stage, interviewed about her life as well as career. She was born Eike Pulwer in East Prussia (now part of Poland). She wanted to be an actress from an early age and worked in France before coming to Britain. There, she changed her stage name to something easier for English-speakers to pronounce, using her middle name of Astrid and her first married name of Frank. She also worked as a model, and had a possibly European ease with nudity, making her British screen debut in 1972 with Au Pair Girls. Regarding Red, she speaks warmly about the cast (of which Gabrielle Drake is still alive and a friend) and her crew: Robert Krasker was a friend of a friend. She says that the BBFC, presumably James Ferman, phoned her to say that they would reject Red at one point (unlikely, given what’s on screen) but relented and gave it the understandable X certificate it went out with.

Over the Mountains (21:29)

Roger Christian talks about his film, which had the likely highest profile on release of anything on this set. He talks about a trip he and a schoolfriend and two girlfriends took to London, which involved catching Doctor Zhivago at the Odeon Leicester Square and it being a lifechanging experience. (His memory’s at fault – its Leicester Square venue was actually the Empire, in 70mm.) He later sneaked into a Bond film being shot near to him then at Pinewood. Showing an early interest in production design, he was advised to take architecture and did so, before being taken on by Oscar-winning designer John Box. Black Angel, which he had first written at school, was one of four scripts up for a grant and a possible release alongside The Empire Strikes Back, and was the one Lucas chose to proceed with. The film was shot with a crew of nine, the most expensive items being the two horses and their trainer. Christian and his DP Roger Pratt watched Kurosawa and Tarkovsky films for inspiration, in particular regarding shooting with anamorphic lenses. As there was no budget for an actress to play the maiden, Christian’s wife Patricia stepped in. There was also no budget for a stereo sound mix, but Bill Rowe did it for the £1000 that was left in the coffers. Christian goes on to say that the short-film programme Black Angel was funded from came to an end soon afterwards but decided to go out with a bang by financing another film for Christian to direct. That was The Dollar Bottom (1980), a 35-minuter which won the Oscar for Best Short Live-Action. (I could suggest that for a future Short Sharp Shocks release, but as it’s not SF, fantasy, horror or a thriller, maybe there’s an argument for a compilation of short films in other genres.) The negative of Black Angel was lost for some thirty years before being found at Universal, after which it has been restored, the results of which are evident on this disc.

Image galleries

On the appropriate discs, we have image galleries for some of the films. All the galleries are self-navigating. That for The Fatal Night (1:04) is supplied by the Zampi family, and consist of stills mostly of Mario at work, plus the press-sheet for the film itself. For Death in the Hand (4:22) we have stills and lobby cards. On Disc Two, the gallery for Red is titled “Astrid’s Little Folder of Wonders” (2:46) and includes shots from her modelling career, a French article where she is captured embracing Fernandel, a big local star if not so much overseas, and the cover of her poetry collection Rent a Soul, as well as material relating to her film on this release. The Sanctum gallery (0:53) shows Brian Davison accepting his award and correspondence regarding his film being denied a showing at the awards ceremony and an answer to a complaint from a member of the public. For Black Angel (2:56) we have stills (some captioned), storyboards and posters.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet with the first pressing of this release runs to thirty-two pages plus covers. The three curators of this set – Vic Pratt, William Fowler and Josephine Botting – expounded at greater length in the first volume, so as with two and three, their introduction to Volume Four keeps it short.

After that, we have pieces on each of the twelve films, by the curators and others, and in three cases the filmmakers. Jonathan Rigby starts off with The Fatal Night, describing its production and reception and calling it “a small classic of British horror”. Josephine Botting is more critical about Death in the Hand, almost to the point where you wonder why it was included in the first place, but has enough to say to justify its presence in this set. Vic Pratt covers the two Strange Experiences films separately and is very complimentary about Night Ride. At this point, they interrupt the programme to bring you “Night Ride: Channelling a Love of Film”, a profile of Denis Meikle by his daughter Sarah Appleton, who features elsewhere in this set as filmmaker and/or editor of the interviews. William Fowler discusses Mirror Mirror and Scarecrow. Next up are Astrid Frank on Red and Bill Davison on Sanctum, plus a piece by William Fowler on The Begotten, whose members include himself. Vic Pratt talks about the two Play Safe films and then we have Roger Christian on Black Angel. As with Astrid Frank’s piece, there are inevitably overlaps between these essays and their interviews on the set, though only if you buy a first pressing of this set, as you should.

The booklet also includes notes on and credits for the extras and plenty of stills, including one supplied by Denis Meikle’s widow and daughter of the man himself meeting Vincent Price.

final thoughts

This is the fourth volume of BFI Flipside’s Short Sharp Shocks line, and so far forty-one films, from under a minute to the borders of feature-length, have been released on Blu-ray. There is scope for lots more, and I’m sure many of us could come up with an extensive wish-list. Who knows, some of them could be able to be licensed for Volume Five, if and when that is released.

Short Sharp Shocks Volume 4

The Fatal Night

UK 1941 | 50 mins

directed by: Mario Zampi

written by: Gerald Butler, Kathleen Connors (adaptation), from the short story The Gentlemen From America by Michael Arlen

cast: Lester Ferguson, Jean Short, Leslie Armstrong, Brenda Hogan, Patrick Macnee, Dandy Nichols

Death in the Hand

UK 1948 | 43 mins

directed by: A Barr-Smith

written by: Douglas Cleverdon

cast: Esme Percy, Ernest Jay, Cecile Chevreau, Carlton Hobbs, John Le Mesurier

Strange Experiences: Halloween Party

UK 1955 | 3 mins

produced by: Derick Williams

cast: Peter Williams, Elspet Gray, Ian Whittaker

Strange Experiences: The Laughing Clown

UK 1948 | 4 mins

produced by: Derick Williams

cast: Peter Williams, Kenneth Hyde

Night Ride

UK 1967 | 19 mins

written and directed by: Denis Meikle

cast: James Whitehead, Denis Meikle, Virginia McNally, John Attfield

Mirror Mirror

UK 1969 | 8 mins

directed by: Garry Parsons

story by: Brian Prodger

cast: Phil Basham, Tony Francomb, Bruce Hales, Cherry Puttock, Jack Waymark

Scarecrow

UK 1972 | 17 mins

directed by: John Sharrad

written by: John Sharrad

cast: Don Blackwell, Dara Merry, Des Waters

Red

UK 1976 | 24 mins

written and directed by: Astrid Frank

cast: Ferdy Mayne, Mark Wynter, Gabrielle Drake, Steve Brownelow, Astrid Frank

Sanctum

UK 1976 | 19 mins

written and directed by: Bill Davison

cast: Pete Steggall

Play Safe: Frisbee / Play Safe: Electricity

UK 1978 | 1 min / 11 mins

written and directed by: David Eady

cast: Bernard Cribbins, Brian Wilde

Black Angel

UK 1980 | 25 mins

written and directed by: Roger Christian

cast: Tony Vogel, James Gibb, John Young, Patricia Christian, Colin Booth, Yvonne Cameron