You in the jail!

A Union colonel teams up with two former Confederate officers in post-Civil War Texas to battle a crooked landowner and the corrupt lawmen in his pay in RIO LOBO, director Howard Hawks’ nostalgic second reworking of his 1959 Rio Bravo. Slarek is back in the saddle for Hawks’ final film, newly released on Eureka’s Masters of Cinema label.

In the final stages of the American Civil War, a shipment of Union gold is being transported by train from Plainsburg to Rocky Ford, where Colonel Cord McNally (John Wayne) and his men are waiting to receive it. Eavesdropping on their telegraph messages with a wiretap is a Confederate group led by Captain Pierre Cordona (Jorge Rivero) and Sergeant Tuscarora Phillips (Christopher Mitchum) as they complete their preparations to ambush the train. Their plan involves heavily greasing the track at the top of a steep climb, disabling the telegraph wire to prevent any calls for help, knocking the driver and the engineer cold, and uncoupling the wagons and letting them roll back down the hill and into a brake simultaneously being fashioned from ropes and tree branches. To force the Union guards out of the bullion car, the raiders have bagged a nest of angry hornets that they plan to hurl through a small window on the roof, insects they will then smoke out to allow them safe access to the gold once the guards have jumped off and the rapidly rolling wagons have been halted. It’s an ingenious plan that goes off without a hitch, though as soon as Cord learns that that the telegraph wire is down, he leads a party of his men to intercept the train. By the time they reach it, the raiders have fled with the gold, and when Cord discovers that the jump from the train has left his close friend, Lieutenant Ned Forsythe (Peter Jason), with a broken neck, he swears to find those responsible and make them pay.

A standard enough premise for a revenge western this may seem, but in truth this is just the first stage of a setup that unfolds over the first half of this close to two-hour movie, a one hour-plus journey whose primary purpose is to bring the main characters together and transport them to the titular town of Rio Lobo. Once there, it’s just a matter of time before we get the line that titles this review. How do we know this? Well, for the few of you out there who are unaware, Rio Lobo was the third in a trilogy of films directed by Howard Hawks and starring John Wayne that began in 1959 with Rio Bravo and was followed in 1966 by El Dorado. Both of the earlier films are built around the same premise, one that involves a small number of seemingly mismatched individuals coming together in a common cause and laying siege in a jail, which comes under repeated attack from gunmen in the pay of a powerful and immoral landowner. It’s thus reasonable to expect that Rio Lobo will follow a similar trajectory and eventually it does, but this time around the group in question holds siege in the jail for a surprisingly lean 15 minutes of screen time. As with its predecessors, though, it’s all about the journey there, and that’s one area where, for all its small but very real pleasures, this final film in the trilogy falls a little short.

The early scenes are still of real interest, as much for the impeccably staged train robbery (which research suggests was actually handled by celebrated former stuntman turned second unit director Yamika Canutt and during which Hawks was injured) as for the unusually positive presentation of characters from both sides of the American Civil War. History and plausibility take a back seat here, with the bitter conflict of the war presented more as a game in which the two sides good-naturedly outmanoeuvre each other. It’s a viewpoint perfectly illustrated when Cord is knocked cold by Tuscarora whilst trying to apprehend Pierre and wakes to find himself in a Rebel camp, where he is treated respectfully and chats with his captors like old friends discussing the result of a friendly wager. Later, when Cord turns the tables and holds Pierre and Tuscarora at gunpoint, there’s still little in the way of hostility between them, and Tuscarora even shares his canteen of corn liquor with his captor. By this point, Cord has realised that someone in his regiment is selling information to the rebels and presses both men for his name. If they give the man up, he promises to set them free, but if not, he’ll take them in, and with Pierre dressed in Cord’s Union officer uniform, there’s a strong chance that he will be executed as spy. The two men elect to take their chances and are thus taken in, but before any action can be taken against Pierre – at least that’s what’s implied – Confederate leader Robert E. Lee signs the articles of surrender and the war is brought to an end. “Damn,” says Pierre in frustration on seeing the newspaper headline, “all this for nothin’!”

A few days later we’re at a Union post, where surrendering Confederate soldiers are being given clothing, medication and a payment of $2, which, while worth a lot more back then than it is today, was still no king’s ransom. Two of those in line are Pierre and Tuscarora, who are not surprised at all to see that Cord is waiting to meet them. He greets these two former enemies almost as friends, then buys them a few drinks (in a genre favourite, he insists the bartender give him the good whiskey that he keeps down on the bottom shelf), and questions them again about the identity of the traitor within his ranks. With the war over, both are now happy to tell McNally what they know, that there were two men whose names they never learned but whom they are able to accurately describe. Cord asks them to do him a favour and contact him if they ever see either of them again, and their relationship is so amicable by now that both readily agree to do so. If only all wars could be conducted and concluded on such friendly terms. When McNally asks them what they’re going to do now, Tuscarora reveals that he’s heading back to Texas and a ranch owned by the man who brought him up, a ranch located in the town of Rio Lobo. Aha! As if the drinks weren’t enough to show that Cord doesn’t hold a grudge against the men whose actions resulted in the death of his friend (he justifies that as an act of war but condemns the selling of information to the enemy as treason, which in his mind is infinitely worse), he gives Tuscarora some extra cash from his own pocket to help him on his way. It should come as no surprise even to newcomers to the trilogy that these three are destined to meet up again later and fight on the same side against a common enemy.

Almost all of the key elements that define what Sheldon Hall describes in the special features as the Rio Trio of films are present and correct here. We have our robust, morally sound and very slightly cynical hero in the shape of Cord McNally, which has Wayne playing essentially the same role as he did in Rio Bravo and El Dorado. The chance-met sidekick role from the previous films is here shared between Pierre and Tuscarora, the latter of whom later sends a message to Cord that starts him on the journey to Rio Lobo. We also have the expected strong-willed female character in the shape of Shasta Delaney (Jennifer O’Neill), who enters the film in True Grit manner seeking justice for the murder of her employer, something Blackthorne sheriff and Cord’s old friend Pat Cronin (Bill Williams) claims he cannot help with because the crime was committed outside of his jurisdiction. And where did this murder occur? Why, Rio Lobo of course. At somewhere like the halfway mark, this band of outsiders is completed with the introduction of the grizzled old man in the shape of Phillips (Jack Elam), Tuscarora’s cranky and trigger-happy adoptive father. I’ll have more to say about him in a minute.

Rio Bravo is now regarded as a genre classic and rightly so and was famously Hawks’s riposte to Fred Zinnemann’s High Noon (1952), a film he disliked for the actions of its characters. The influence of Hawks’s film on a later generation of filmmakers is most clearly visible in John Carpenter’s second feature, Assault on Precent 13 (1976), which updated the central concept of a group of mismatched individuals trapped inside a jail and under siege from a gang of armed criminals to a modern urban setting. Carpenter even named one of the film’s characters Leigh Brackett after the co-screenwriter of Rio Bravo, as well as editing his film under the pseudonym of John T. Chance, the name of John Wayne’s character in Hawks’ original. If that wasn’t enough, in 2001 Carpenter reworked the same premise in a science fiction setting as Ghosts of Mars. The popular opinion is that both El Dorado and Rio Lobo were inferior reworkings of the Rio Bravo formula, but I’ll go to bat any day for El Dorado. Although – unsurprisingly – not as innovative as its predecessor, El Dorado shines in its consistently smart and witty script, the only one of the three films whose screenplay is solely credited to Leigh Brackett, being an adaptation of the 1960 novel The Stars in Their Coursesby Harry Brown.1

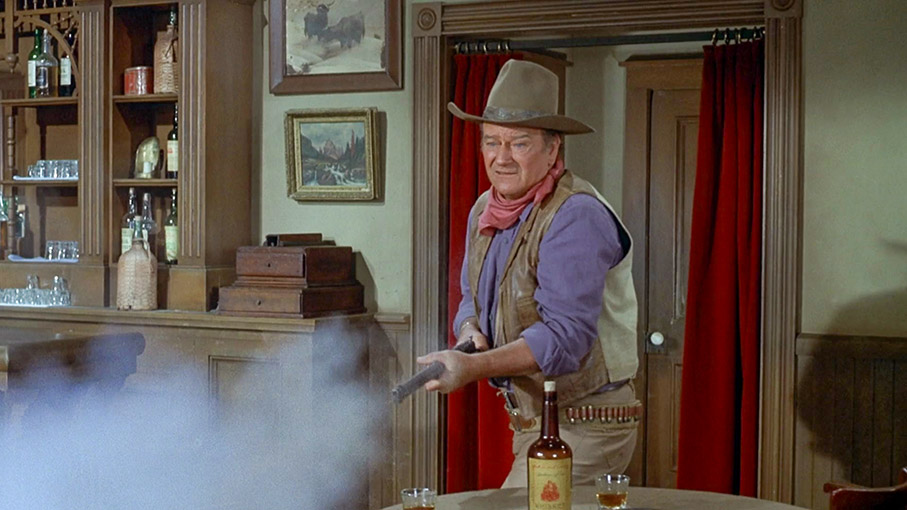

It also has a belter of a cast, with Wayne here teamed with Robert Mitchum as the washed-up and drunken Sheriff J.P. Harrah and a young James Caan as the vengeful Alan Bourdillion Traherne, aka ‘Mississippi’ (in Rio Lobo, Cord gives Pierre the nickname ‘Frenchy’). In support we have the likes of Charlene Holt, Paul Fix, Arthur Hunnicutt, R. G. Armstrong, Ed Asner and Christopher George, all of whom make a real impression. Although Brackett also has a co-screenwriting credit on Rio Lobo, word is that she was only brought in later by Hawks after he fired the film’s original screenwriter, Burton Wohl, and she later claimed that all she really did was patch over the plot holes. The dialogue certainly lacks the sharp wit of Brackett’s screenplay for El Dorado, with only occasional flashes of the amusing banter of that film, my favourite being Pierre’s irritated response to Shasta agitatedly asking why he (partially) undressed her before putting her to bed after she fainted, a line that I’ll leave for the film itself to reveal. There’s also a genuinely amusing encounter between Cord and town dentist Dr. Ivor Jones (David Huddleston), who pretends to be dealing with a bad tooth whilst secretly passing information to Cord, whom he encourages to shout in pain to convince the crooked lawmen watching from outside that his proffered dental complaint is on the level. It’s possibly meant as an in-joke when Jones gives Cord a sharp injection that makes him genuinely yelp in pain. “Ow! That’s the real stuff!” the startled Cord complains, to which Jones replies, “Well, if you’d have been a good enough actor I wouldn’t have used it.”

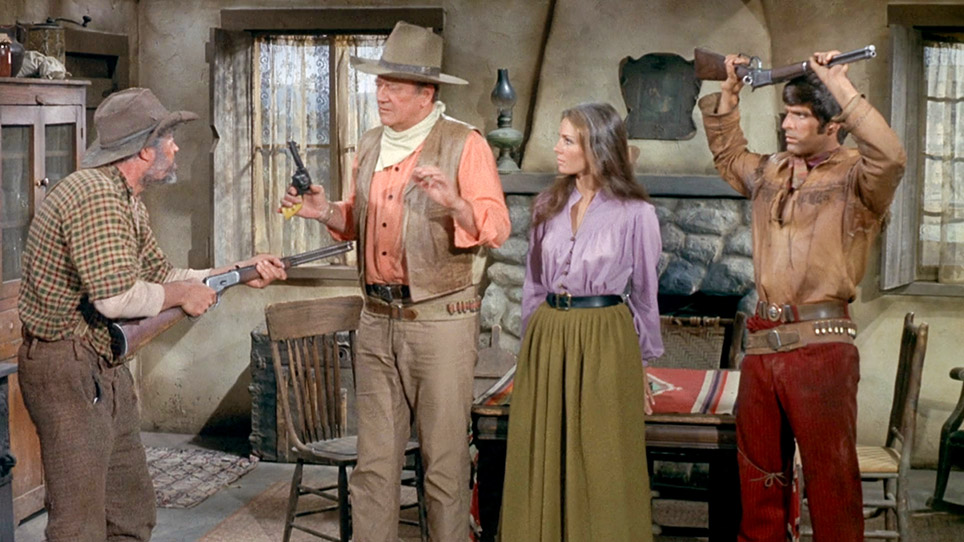

The cast is solid enough, with Jorge Rivero painting Pierre as a dependable sidekick, and Robert Mitchum’s son Christopher making for an easily likeable Tuscarora. Jennifer O’Neill has the required spark as the self-confident Shasta, berating Sheriff Cronin for his lack of action and sharply dismissing Cord the moment he opens his mouth to intervene. Making an instant impression is Sherry Lansing as Rio Lobo local Amelita, whose house Pierre barges into to hide from men working for corrupt Sheriff Tom Hendricks (Mike Henry), where the topless Amelita (she has her back to the camera and her arms crossed over her chest, so control yourselves), far from being outraged at this intrusion, is only too keen for Pierre to stay. Later in the story she plays a pivotal role, as did the actress herself eight year later when she was appointed in the role of Vice President in Charge of Production at Columbia. It didn’t end there. So successful was she in the job that she subsequently became the President of 20th Century-Fox, then formed the independent production company Jaffe-Lansing with producer Stanley R. Jaffe, and in 1990 became Chairman of Paramount Pictures’ Motion Picture Group. Keep that in mind when you watch her introductory scene. John Wayne plays John Wayne in that confident, easy-going, slow-drawl way that was his signature, and despite claims that he was too old and fat for the role, it fits him like an albeit well-worn glove. But even if these performances fail to excite you, it’s worth hanging in there for the late film introduction of Jack Elam’s Phillips, a hugely entertaining crazy old geezer turn that instantly shifts the film into a higher gear but apparently irritated Wayne, who felt that Elam was stealing every scene in which he appeared, which he absolutely was.

Shortly before the release of Rio Lobo, Hawks was interviewed on stage at the National Film Theatre in London (now BFI Southbank), a transcript of which was publish in the Spring 1971 issue of Sight & Sound, in which the claimed that when approached about the project, John Wayne responded, “Do I get to play the drunk this time?” 2 a clear indication of this film’s twice recycled premise. I have read that Hawks himself later expressed unhappiness with the film and that he did not get on with female lead Jennifer O’Neill, though I’ve not yet read an authoritative confirmation of this claim. The film did certainly not find much critical favour on its release, with even Roger Ebert rounding off his largely positive review with, “I’m sorry to say, however, that Rio Lobo is just a shade tired, especially after the finely honed humor [sic] and action of El Dorado.”3

For all that, Rio Lobo remains a likeable if disappointingly unadventurous final movie from a director whose best films are justifiably part of the movie pantheon. It starts at a gallop, then ambles amiably if predictably along, buoyed by Jerry Goldsmith’s lively western score, though does pick up a bit with the introduction of old man Phillips. It also concludes on what could be read as an unintended but prophetically symbolic note (big spoiler ahead). With the bad guys defeated, Wayne limps away from the camera towards his final six years as a screen actor, supported on his way by a strong-willed young woman who was soon to carve a successful career as a production executive for three major movie studios. How poetic that she eventually rose to be the head of Paramount, the very studio responsible not just for this restoration of Rio Lobo, but also for the 1976 The Shootist, director Don Siegel’s gorgeously realised elegy to ageing gunfighters that gave Wayne one of the finest and most moving roles of his career.

sound and vision

As noted above, the 1080p transfer on this Eureka Masters of Cinema Blu-ray release was sourced from a 4K restoration by Paramount and is presented in the film’s original aspect ratio of 1.85:1. The resulting image is consistently solid, with clearly defined detail and a generous contrast range that was enabled in part by cinematographer William H. Clothier lighting the daytime interiors almost as brightly and evenly as the streets outside. When night falls, the picture is appropriately graded to suit, and despite darkening the image, Clothier keeps all of the appropriate picture detail clearly visible. There is no picture movement within the frame and no obvious signs of damage or wear, and while the transfer is largely clean, there are a few tiny dust spot ‘sparkles’ visible throughout, which occasionally increase a little around what I’m guessing were the end or start of reels. A fine film grain is visible throughout and the disc is encoded region B.

There are two soundtracks on offer, with the film’s original mono track presented in Dolby Digital 2.0 and a more recent surround remix in DTS Master Audio 5.1. Both are clear and boast a decent tonal range, but the 5.1 track just wins out on this score. Surprisingly, this is not AC3 recording of the mono track but a proper remix, with appropriate directional use of the full surround stage, especially during the opening train hijack.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

special features

Back to the Old West (10:23)

Author and western scholar Austin Fisher states up front that Rio Lobo is a film of two halves, and is particularly interested in the first, which focusses on the need for post-Civil War reconciliation. He notes that the conflict is presented in a good natured way, with the humane treatment of the defeated Confederates here contrasting sharply with its more realistically cruel presentation in Sergio Leone’s The Good, the Bad and the Ugly (Il buono, il brutto, il cattivo, 1966). He suggests that Wayne’s character was effectively an amalgamation of his previous roles and highlights the significance of such a nostalgic reprisal of the western of past years arriving at a time when the genre was undergoing revisionist change.

Directed and Produced by Howard Hawks (13:32)

Author and film historian Sheldon Hall states up front that while he is sceptical of the auteur theory, he does believe there are directors to whom it clearly applies, Howard Hawks included, a point on which he elaborates through a combination of research and personal experience. He notes that unlike John Ford, Hawks was more interested in the relationship between the male lead characters than the historical background, something clearly evident in what he describes the director’s Rio Trio – Rio Bravo, El Dorado and Rio Lobo – whose shared character models he also identifies. He points out that the majority of the members of the team that come together to fight the evil landowner in Rio Lobo are younger than their equivalents in the earlier films and has an engaging story about how about his first viewing of the film on BBC TV was unexpectedly disrupted by real-world events.

TV Spot (1:04)

A brief peek behind the scenes is followed by a spattering of clips from the film that make it look almost like an action movie in western clothing. I’m guessing this trailer was a rare grab, given the softness of the monochrome image.

Booklet

One of the shorter Masters of Cinema booklets at just 16 pages (and that includes the covers) that is dominated by an essay on Rio Lobo by film writer and critic Richard Combs, which mainly consists of a breakdown of the plot and a little analysis of some elements. The main credits for the film and the usual viewing notes are also on board.

final thoughts

The final film of one of the great American directors must have felt old-fashioned even back when it first hit cinemas, given the revisionist turn the genre had taken in the mid-to-late 60s in Italy and the US. It’s nonetheless an engaging enough if (perhaps too) easy-going work with young secondary leads, three prominent female characters, and a delightfully showy performance from Jack Elam. Likeable though the film definitely is, I’ll still go with Rio Bravo or Ed Dorado any day if I have the choice. A smattering of tiny dust spots aside, the transfer is a robust one, and the special features, though light, are well targeted.

Rio Lobo

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

- Said Leigh Brackett about the script of El Dorado: “I wrote, what was to my way of thinking, the best script I had ever done in my life…[But] the more we got into doing Rio Bravo over again the sicker I got, because I hate doing things over again. I kept saying [that] to Howard, and he’d say it was okay, we could do it over again… You know, the guy that signs the final check has the final say.” https://www.criminalelement.com/adventures-in-screen-writing-the-amazing-leigh-brackett-rio-bravo-el-dorado-the-long-goodbye-the-empire-strikes-back-the-big-sleep-hall-of-famer-jake-hinkson/[↩]

- https://www.bfi.org.uk/sight-and-sound/interviews/audience-howard-hawks-1971[↩]

- https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/rio-lobo-1970[↩]