The A List

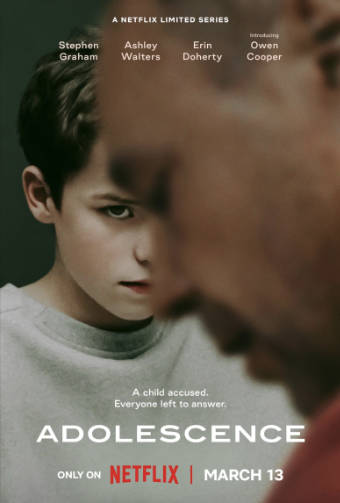

ADOLESCENCE

The last thing I watched on Netflix before cancelling my subscription proved to be one of the very best programmes ever screened on the platform. In an unspecified Yorkshire town, a large-scale police operation kicks into action, as armed officers break down the door of a suburban house, not to foil a terrorist plot or to bust up a drug gang but to arrest a terrified 13-year-old boy named Jamie Miller, much to the frightened confusion of his distraught family. It turns out that Jamie has been identified as the prime suspect in the violent murder of a schoolgirl, a crime that he initially denies but that the evidence clearly suggests that he was very likely responsible for.

Co-written with Jack Thorne and actor Stephen Graham – who also plays Jamie’s father in a career best performance – and directed by Philip Barantini, it’s a timely and deeply troubling exploration of a range of very real modern issues, from toxic masculinity and the role of social media in the radicalisation of disaffected youth to a string of questions surrounding parenting, bullying, youth crime and education. Evoking memories of the celebrated (and at the time, controversial) 1978 British TV mini-series Law & Order, in which criminal activity, police corruption and abusive imprisonment were explored from four different viewpoints over as many episodes, Adolescence does likewise with its story, the key difference here being that each episode is captured in a single unbroken take. What may at first seem like a gimmick – albeit one that Barantini and Graham had already put to excellent use in the 2021 Boiling Point – soon proves to be an essential aspect of the series’ discomforting intimacy, making us as viewers feel less like observers than active participants in the unfolding drama. Organisational and technical challenges aside (the logistics of pulling off the second episode set in a school genuinely made my head spin), the technique just works here, peaking in the extraordinary two-hander of episode 3 in which police psychologist Briony Ariston (Erin Doherty) attempts to get inside the resistant Jamie’s head, during which there were times that I felt genuinely trapped in a room that I intermittently wanted to flee from. Superbly acted by a consistently excellent cast, but special praise has rightly been reserved for young first-timer Owen Cooper, whose performance as Jamie is one of the most believable and ultimately chilling portrayals of troubled and misdirected youth ever committed to film or digital.

BRING HER BACK

Following the unexpected death of their single parent father, stepsiblings Andy and the near-blind Piper are placed with foster mother Laura for three months until Andy comes of age and can apply for guardianship of his sister. The relentlessly upbeat Laura is instantly welcoming, almost too enthusiastically so, and she seems equally devoted to her existing charge, Oliver, despite his vocal silence and troubling stares, but it gradually becomes apparent that something is not quite right here.

Last year, I had Talk to Me, the debut feature from former YouTube creators Danny and Michael Philippou, on my B list, and the considerable promise and confidence they showed with that film is delivered on in spades in this impeccably crafted follow-up. An object lesson in slow-build suggestive horror, it keeps its cards close to its chest (despite what retrospectively plays like an opening scene pointer) and, in common with its predecessor, gives its story and characters time to breath before making its first significant moves, which it tantalisingly drip-feeds rather than hitting us with a sudden shock twist. Key to why this works are two strong central performances from young actors Billy Barratt and Sora Wong – and full marks to the Philippous for casting a genuinely sight-impaired newcomer in this crucial role – and a dynamite turn from Sally Hawkins as Laura, who manages to convey a sense that something is really off from the moment we meet her simply by being just a little too joyful at Andy and Piper’s arrival. When the explanations come, they are handled with intelligence and a real sense that even the aspects that would normally plays as fantasy horror feel oddly and movingly grounded in reality. What emerges is a captivating, increasingly tense, ultimately moving and impressively mature film about loss, grief and motherly devotion, and one that for me seems to get better with every viewing.

COMPANION

I swear, there’s a special place in cinematic hell for marketing departments. a Companion as an example, a film that is best viewed with no foreknowledge of how its story will unfold. All you need to know to get you started is this: newly in love couple Iris and Josh plan a weekend away with Josh’s friends Kat, Eli and Patrick at a secluded lakeside house owned by Kat’s boyfriend Sergey, but not everyone is who they initially appear to be. The only ambiguous pointer to where the film will later head is designed to intrigue without revealing the specifics, as the almost cheesy supermarket meet-cute between Iris and Josh concludes with the couple laughing together and Iris reflecting in voiceover, “There were two times I felt truly happy. First, the day I met Josh; second, the day I killed him.” That should be all the hook anyone needs, as if you go in blind as I did, there’s a belter of a plot twist in the first half-an-hour that some complete idiot thought would be great to put in the bloody trailer! Even most of the posters I saw effectively give the game away. Fortunately, even if you were tipped off about this, there’s a second twist later that should catch you by surprise.

I’m thus obviously not going to reveal any more about what unfolds on the off chance you’ve not seen the film and have managed to avoid such marketing and any spoiler peppered reviews. I will instead confine myself to stating that, for me at least, Companion proved a hugely enjoyable and inventive ride, one that successfully straddles several genres and that laces even the tensest scene and the moments of sudden violence with black humour. Nicely handled all round by writer-director Drew Hancock in his feature debut, who also gets the best from a fine cast that includes Sophie Thatcher, Jack Quaid, Lukas Gage, Megan Suri and Harvey Guillén, all of whom get to shine for reasons I can’t get into without ruining the fun for first timers.

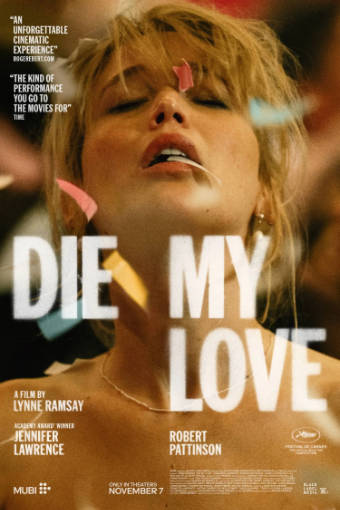

DIE MY LOVE

Grace and Jackson are young lovers with a passion for each other and for life in general. In a long held static opening wide shot, they are shown exploring the isolated countryside house that Jackson has inherited from his late uncle and in which they will soon make their home, but after Grace becomes pregnant and gives birth to their child, their previously harmonious relationship begins to fracture, which triggers a slow decline in Grace’s mental health.

A straightforward enough setup, perhaps, but in the hands of Ratcatcher, Movern Callar, We Need to Talk About Kevin and You Were Never Really Here director Lynn Ramsay, what unfolds is complex, layered and deeply troubling study of postpartum depression and psychological deterioration. Adapted by Ramsay, Enda Walsh and Alice Birch from the book of the same name by Ariana Harwicz, it’s built around a powerhouse performance from Jennifer Lawrence as Grace, with strong support from Robert Pattison as Jackson, Sissy Spacek as Grace’s sleepwalk-with-a-shotgun mother, and Nick Nolte as her dementia addled father. I’m not going to claim it’s an easy watch, as despite humorous moments (“It changes you,” one woman tells Grace about motherhood, adding with a small laugh, “I think I nearly lost my mind for the first six months,” to which Grace cynically replies, “When do you think you’ll be getting it back?”) it proves increasingly difficult, emotionally fraught, and thanks in part to the Academy framing, sometimes claustrophobic viewing, but also, in that way that Ken Loach’s films could be simultaneously punishing and rewarding, a deeply enriching experience.

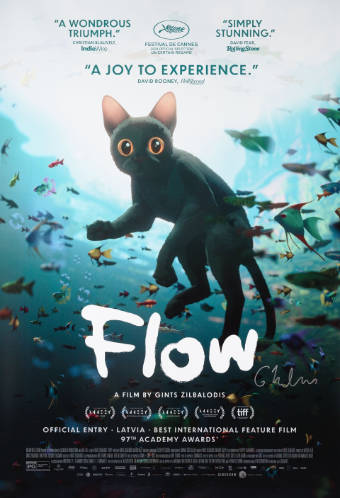

FLOW

Sometimes, just occasionally, the Academy gets it right, and I’d argue that this is definitely the case with this second feature from Latvian filmmaker and animator, Gints Zilbalodis, which bagged this year’s Best Animated Feature Film Oscar. In what feels like post-Rapture world now devoid of humans, a solitary cat has its life turned upside-down by the arrival of an almost biblical flood, forcing it to seek refuge from the rapidly rising waters on a passing boat on which an easy-going capybara is already travelling. As the vessel drifts along, the two are joined by an excitable labrador, an avaricious lemur, and eventually a large secretary bird that, like the dog, has taken an unexpected liking to the wary cat but appears keen to steer the boat towards a very specific location.

Without question the most innocently magical experience I had watching a new film all year, this beautifully designed and animated work takes its cue from Michael Dudok de Wit’s equally spellbinding The Red Turtle (La tortue rouge, 2016) in playing out entirely without dialogue, with the thoughts and emotions of the animals conveyed entirely through character animation and sounds recorded of their real-world equivalent. Astonishingly, the film was created primarily using Blender, a popular but free and open-source 3D computer graphics program, and has a distinctive visual style, with the posterised look of the animals set against sometimes strikingly realistic graphical backgrounds (the water in particular is beautifully rendered). None of this would matter a hoot if the characters and story weren’t engaging but they absolutely are, to the point where I ended up watching it repeatedly over the course of a two week period. When I showed it to my most appreciative partner, she had a dream that night that was clearly inspired by the film and a few days later was eagerly demanding to watch it again.

FRANKENSTEIN

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus has, over time, established itself as one of the defining works of horror literature, being the basis for not just the first film adaptation of a horror novel (the 1910 one-reeler directed by J. Searle Dawley), but also the 1931 Universal classic that helped give birth to the cinematic horror genre. Since then, there have been countless, often inventive and entertaining takes on the story, precious few of which were faithful to Shelley’s original. Do we really need another? Enter Mexican maestro Guillermo del Toro, for whom this had apparently been a dream project for many years, and finally became possible when Netflix stumped up a whopping $120 million to allow him to realise his vision. This, of course, meant that it was only in cinemas for a brief token run to allow it to qualify for awards before moving over to the streaming service, and a film of this grandeur really deserves to be seen on the biggest screen possible.

Yes, there are deviations from Shelley’s original, but the depth and sheer scale that del Toro brings to his interpretation provides ample compensation, as does his decision to split the film into two halves and tell the story from the viewpoint of both Victor Frankenstein and his creation. Oscar Isaac impresses as an energised and sometimes infuriatingly driven Victor, Mia Goth entrances as the only one who genuinely empathises with the Creature, and Charles Dance is perfect casting as Victor’s arrogant and abusive father. Best of all is Jacob Elordi, who, despite having his features buried beneath extensive makeup, is able to explore the humanity and suffering of the Creature to such a degree that it becomes all too easy to ask that old favourite question regarding who the monster really is here. Gorgeously shot by del Toro regular Dan Laustsen, with breathtaking production design by Tamara Deverell and a handsome score by the ever-reliable Alexandre Desplat, this was another film that my partner insisted we watch twice in a row, a request that elicited no complaints from me.

THE GIRL WITH THE NEEDLE [PIGEN MED NÅLEN]

In 1919 Copenhagen, poverty-stricken young Karoline is evicted from her apartment and forced to move into a damp and squalid room, which she pays for through lowly work as a seamstress in a factory. Her application for a widow’s compensation is rejected because, although she hasn’t heard from her husband Peter since he went off to war, he has not officially been declared dead, but employer Jørgen takes pity on her, and a romantic and sexual relationship develops between them. When Karoline becomes pregnant, Jørgen appears ready to marry her, but Karoline’s hopes of future happiness are upended when Peter returns from the war facially mutilated, and Jøgen’s overbearing mother forbids her son from marrying a woman she regards as an opportunistic commoner.

Co-written (with Line Langebek) and directed by Magnus von Horn, The Girl With the Needle (and yes, the true meaning of that title does becomes grimly clear) is visually both a striking and simultaneously sobering work, being shot by cinematographer Michal Dymek in the Academy ratio in stark black and white, which only serves to emphasise the grime and the dank of the downtrodden quarter of the city in which Karoline is forced to live and work. In common with Die My Love, this is not a film you watch to lift your spirits and send you off with a cheerful spring in your step, but is so well made, so compellingly told, and is performed with such commitment that I was riveted from the opening scene.

I’M STILL HERE [AINDA ESTOU AQUI]

I’ve been following the career of Brazilian director Walter Salles ever since we screened his 1998 Central Station [Central Do Brasil] at the cinema-based film society that I used to co-run. Both Camus and I were captivated by his 2004 The Motorcycle Diaries [Diarios de motocicleta], though I have to admit to being less than blown away by his disappointingly lightweight remake of Nakata Hideo’s genuinely scary and subtextually gut-punching Dark Water(2005). I can’t say whether it was the uneven critical response to his 2012 film of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road that was behind the 12-year hiatus from directing that followed, but when he returned to Brazil and the director’s chair in 2024, he delivered what may be his finest film yet.

As the film begins, we’re introduced to the various members of the Paiva family in an energetic, almost documentary-like manner. It’s a picture of lively and carefree happiness, only tainted at all by an opening caption that informs us that this is Rio de Janeiro in 1970, “under military dictatorship.” You just know that statement is going to become relevant sooner or later. Despite his easy-going demeanour, we learn that the father, Ruebens, was a former congressman and that he and his close friends continue to secretly oppose the new military government and support political expatriates. Then one day a group of plain-clothed government goons show up at the house and lead Ruebens away, an action he calmly cooperates with but that deeply worries his family. When he fails to return and his wife Eunice visits the local military detention facility to enquire of his whereabouts, she is also arrested, held in grim conditions for 12 days and repeatedly questioned. Once released, despite the potential danger to her and her family, she continues her quest to discover what has happened to her husband.

Such is the basis for one of the most compelling political dramas in recent years, one that neither sugarcoats nor sensationalises the actions of these amoral men who appear tasked with silencing all opposition and punishing anyone who has ever openly favoured democracy over dictatorship. This approach proves devastatingly effective, with Salles allowing us to spend considerable time getting to know and thoroughly like the family before the fateful visit completely changes the direction and tone of the film. Once this happens, the tension is cranked up, with scenes of cold intimidation and psychological torture punctuated with subtle suggestions that something much worse could be waiting, whether it be the overhead screams of a prisoner in a different room or the brief shot of officers washing the blood from a prison corridor floor. The performances are terrific across the board, but as Eunice, Fernanda Torres delivers an acting masterclass so rivetingly real that’s she genuinely deserves every award going (she was the first Brazilian actress to win a Golden Globe in an acting category). An extraordinary work with a horribly contemporary ring given what’s unfolding in Trump’s America and made all the more impactful by the knowledge that this is a recreation of a true case and adapted from the memoir Ainda Estou Aqui by Eunice’s son Marcelo.

LATE SHIFT [HELDIN]

If you’re looking for a film to lift your spirits and instil you with hope for the future, then this almost documentary-like portrait of a nurse working the night shift at an understaffed Swiss hospital from writer-director Petra Biondina Volpe is probably not for you. Yet I’d still urge you to hunt it out and see it if you can, if only to get a clearer understanding of the pressures under which medical staff the world over have to work and the potential healthcare crisis waiting just around the corner.

The action centres completely around nurse Floria Lind (a superb and completely believable Leonie Benesch), from her arrival at work one evening until she leaves the following morning, observing her as she juggles a variety of tasks and staff requests with a professionalism and attention to detail that for a short-term memory deficient bubblehead like me seems to border on the superhuman but is doubtless standard operating procedure for many healthcare workers. Frustrations inevitably mount as Floria is pulled every which way by individuals whose only concern is their relatives, their patients, or in the case of one initially infuriating private patient, themselves. Perhaps inevitably, these do eventually boil over and lead to one potentially dangerous error (which is handled with consummate professionalism by all) and Floria losing her rag with someone that a couple of hours later she is doing her best to comfort after the reasons for his selfish behaviour become apparent. It’s a riveting if sobering watch with a deeply concerning parting warning about the consequences of the soon-to-be critical shortage of nursing staff in the western world.

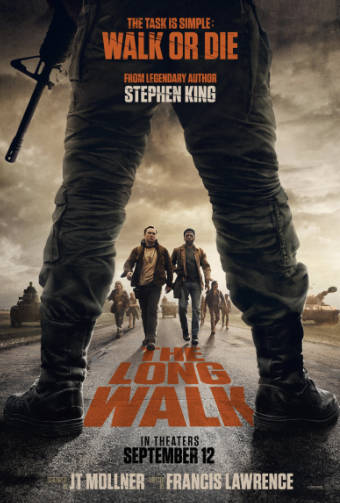

THE LONG WALK

In an alternate dystopian 1970s America under totalitarian rule (yeah, I know) where poverty is rife, an annual contest is held in which young male volunteers are chosen by lottery to compete in a gruelling and deadly walking contest that is broadcast nationwide as an inspirational entertainment. The rules are simple. Contestants must maintain a speed of 5kph, and if they drop below this and fail to heed the two warnings that follow, they will be executed on the spot. The walk continues until only one contestant is left standing, with the winner rewarded a large cash prize and granted a single wish.

Adapted by JT Mollner from the novel of the same name by Stephen King (writing under the pseudonym of Richard Bachman), there are obvious parallels here with King’s own The Running Man, as well as the Hunger Games books and films, and especially Fukasaku Kinji’s Battle Royale (2000) and the Korean series Squid Game (2021). As it was with those last two examples, the outlook for almost every character we meet here is bleak from the off, and what makes the inevitability of what lies ahead so gut-wrenching is how likeable some of them prove to be, how upbeat their collective mood is as they set off, and how quickly friendships that in other circumstances would be the basis of lifelong bonds are formed.

Having previously directed five of the Hunger Games films, Francis Lawrence must have seemed a logical choice to helm this similarly themed work, but for my money those earlier movies play like trial-runs for what he delivers here. The scene is economically set with the minimum of exposition and unfolds compellingly, thanks in no small part due to Mollner’s thoughtful and character-centric script and a string of excellent performances from the likes of Cooper Hoffman, David Jonsson, Garrett Wareing, Tut Nyuot, Charlie Plummer and Ben Wang. And yep, that’s Mark Hamill behind the beard and shades as the bombastic Major egging the contestants on. Inevitably and increasingly it proves a tough watch, as characters you’ve come to know and like and/or feel sympathy for are unceremoniously executed for the crime of being tired, in pain, seriously injured or just needing to take a dump. It’s upsetting but arresting viewing, and one of several films on this list that also plays as a commentary on the dark direction in which modern America is heading.

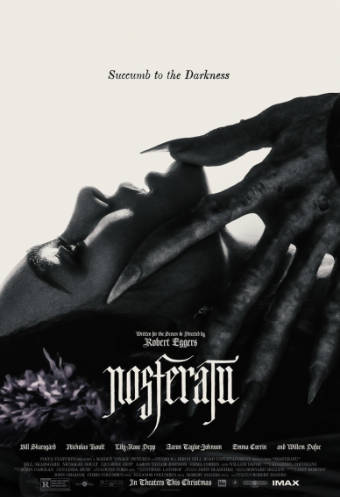

NOSFERATU

Although technically a 2024 film, Robert Eggers’ re-imagining of the grandfather of vampire films hit UK cinemas on 1 January 2025, so in my book it qualifies for that year’s list. And it nearly didn’t, though only for one small niggle I had with this otherwise handsomely realised work. This is, of course, the second reinterpretation of FW Murnau’s silent 1922 masterpiece, Nosferatu, eine symphonie des grauens, which was also reworked by Werner Herzog in 1979 as Nosferatu the Vampyre, a fascinating and moodily effective work whose UHD release last year resulted in me botching my part of the review so badly that the mere mention of that title now prompts me to shudder in shame.

I have to admit that I went into this one a little conflicted. I’m a huge fan of Murnau’s original and am rarely impressed with remakes of great movies, but I also hold Eggars’ previous films The Witch (2015), The Lighthouse (2017) and The Northman (2022) in extremely high regard. What I got was a work so dripping in atmosphere and suggestive dread that I was very quickly won over. Lily-Rose Depp shines brightest here as the tortured Ellen Hutter, and Bill Skarsgård consolidates his reputation as the go-to guy for monsters as Count Orlok, whose appearance differs markedly from the now iconic creation played by Max Schreck in 1922, but is every bit as disturbing in his own way.

My only small quibble – spoiler alert for any newcomers out there – is with the concluding scenes. In Murnau’s original, Ellen’s decision to sacrifice herself and keep Orlock by her bedside until sunrise to destroy him was hers alone. In this film, she has to have this realisation affirmed and be assured that this is the only way to defeat Orlock by a male authority figure in the shape of Professor Albin Eberhart von Franz (Willem Dafoe), which ironically makes the century-old original feel a tad more progressive than this modern remake. It’s still a hell of a film, and the production design (Craig Lathrop), cinematography (Jarin Blaschke) and sound design (Michael Fentum) are all superb.

ONE BATTLE AFTER ANOTHER

Interracial couple Pat Calhoun and Perfidia Beverly Hills are members of a Weather Underground style revolutionary group known as the French 17, which stages armed raids on camps in which immigrants are being detained, imprisoning the guards and freeing the detainees. Whilst storming one facility, Perfidia sexually humiliates its commanding officer, Colonel Stephen J Lockjaw, who becomes attracted to her to the point of obsession, which leads to a blackmail-triggered sexual liaison between the two. Months later Perfida gives birth to Charelene, who may or may not be Bob’s daughter, and while Bob feels it’s time to settle down and take care of their new child, Perfidia continues to fight for the revolutionary cause. When a fund-raising bank robbery goes bad, Perfidia is chased and caught and assured by Lockjaw that she faces a lifetime in prison unless she starts naming names, which lands her in a witness protection programme. With the group now going to ground, Pat and Charlene are supplied with new identities by the French 17 and become Bob and Willa Ferguson. 16 years later, Bob is living a deeply cautious if drug and alcohol fuelled existence in a cabin in the woods with the teenage Willa, who regards his over-protective measures as paranoia. But with Lockjaw looking to join an elite secret society whose demands include complete racial purity, he abuses his military position in an effort to locate this potential evidence of his sexual assignation with Perfidia with the intention of eliminating Bob and kidnapping Willa.

Cards on the table, I’ve been a huge fan of Paul Thomas Anderson’s work since I first saw Hard Eight (1996) and was absolutely knocked sideways by Boogie Nights (1997) and especially Magnolia (1999), which remains my favourite PTA film, so I was predisposed to be at the least sympathetic to his latest even before I sat down to watch it. Even with that in mind, I genuinely wasn’t ready for just how much I would enjoy this film and how in tune with my own sensibilities it would prove to be. For me, everything clicks perfectly here, from the gorgeous, multilayered fluidity of the storytelling to performances from old hands and newcomers alike that I have little doubt will be forever ranked as being amongst their best. As Bob, Leonardo De Caprio scores in both his spaced-out paranoia and his urgent desperation to locate Willa when the shit goes down and the two are individually forced to go on the run. His increasingly furious anger at the French 17 phone operative who calmly demands a password that he cannot remember due to years of drug taking gave me some of the loudest laughs I had watching a film all year. Newcomer Chase Infinity is terrific as the initially frustrated but later desperately resourceful Willa, and Sean Penn brings so much to the character of Lockjaw, from his distinctive gait to the way he almost unconsciously nibbles at his top lip during moments of emotional tension. I’ll also give a shout out to Teyana Taylor as Perfidia, Benicio Del Toro as Sensei Sergio St. Carlos, a laid-back karate instructor with a secret life, and James Raterman, who is quietly and realistically terrifying as military interrogator Danvers.

Anderson’s direction is never showy and propels the film forward at a measured pace that intermittently accelerates in extraordinary sequences that are worthy of stand-alone study. A prime example comes once the alarm is raised and Bob and Willa have to independently flee for their lives, Willa with the help of French 17 operative Deandra (Regina Hall), Bob assisted by Sergio and his underground organisation. It’s a beautifully paced, staged and filmed set of encounters whose unbroken continuity is aided immeasurable by the deceptively simple, almost avant-garde rhythmic piano plinking of Johnny Greenwood’s consistently masterful score.

As well as being one of the most engrossing and entertaining films of the year, One Battle After Another proves to be a genuine tonic for the resistance. Where the events recreated in I’m Still Here are likely by chance be reflective of elements of Trump’s America, it’s clear that the parallels are very deliberate here. Raids on businesses to swoop up immigrants are launched on false pretences; the military descends on a sanctuary city as cover for the commanding officer’s personal vendetta; French 17 members are executed on the street without due process; wealthy people in positions of power have formed a deeply racist secret society; good people band together and use their meagre resources to secretly assist desperate immigrants and hide them from military and police raids… Need I go on? The film also leaves us with a positive message about how the spirit of those once hopeful would-be revolutionaries lives on in the need to keep protesting in the face of government oppression and injustice. I didn’t just love this film, it genuinely warmed my heart.

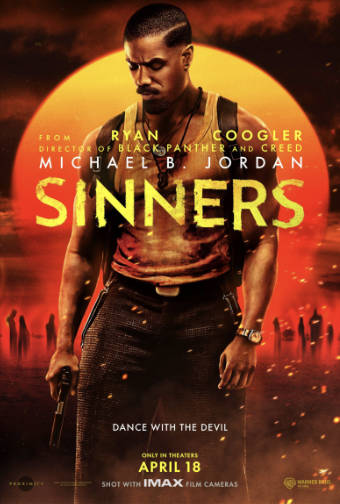

SINNERS

In 1932, after several years working for the Mob in Chicago, twin brothers Elijah and Elias Moore, aka Smoke and Stack, return to their Mississippi hometown as wealthy men, and purchase an abandoned sawmill with the aim of transforming it into a juke joint. Their reputation precedes them, and they waste no time in recruiting local talent and help, and while the opening night is a packed and intensely lively affair, it is soon upended by the arrival of an unexpected and predatory evil.

If you’ve not yet seen writer-director Ryan Coogler’s glorious Sinners and know little about how it unfolds, then skip to the next film on this list and go into the film cold to get the most out of its midway genre switch, though I’m guessing there will be few who are not aware of it by now. For those who do know, well, if you’re looking to put a completely new spin on the vampire genre, then Sinners is an object lesson in how to go about it, in part because it’s so compelling as a period drama even before the story takes a supernatural turn, an aspect that then becomes integral to the narrative, the characters, and the social subtext. Coogler’s direction is boldly inventive, crafting a film in which music is not used solely to enhance the action but becomes to the film’s narrative structure. This peaks in an extraordinary single shot sequence in which the camera floats around the juke joint and the fabric of time seems to break down, as black musicians from the film’s past, present and future collide and overlap in one of the most visually and aurally stunning sequences I watched all year. It’s an extraordinary work with terrific acting across the board, though I have to give a special shout to Michael B Jordan, whose dual performance as Smoke and Stack (so good is the effects work that I had to check the cast list to be sure Jordan didn’t also have a twin brother) is so nuanced that despite the similarity of their appearance, I never had trouble telling one from the other.

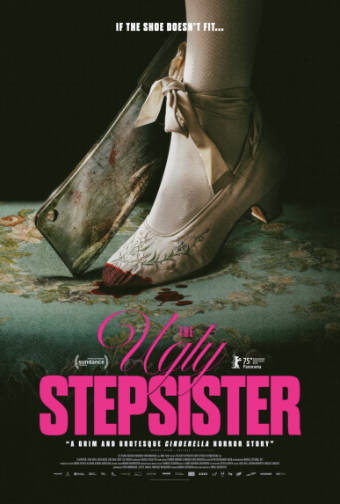

THE UGLY STEPSISTER [DEN STYGGE STESØSTEREN]

Plain and dumpy Elvira dreams of marrying the kingdom’s most desirable bachelor, Prince Julian, whose collection of published romantic poetry she constantly dotes on. Her cash-strapped and widowed mother Rebekka is meanwhile set to marry seemingly wealthy suitor Otto, and when she, Elvira and Elvira’s younger sister Alma first arrive at his stately home, Elvira is wonderstruck, particularly when she discovers that Prince Julian’s castle is visible from her new bedroom window. When Otto unexpectedly keels over and dies just hours after the marriage, Rebekka discovers to her horror that despite appearances, he was also broke and that he married her under the belief that she was loaded. With the family facing a potentially bleak future, news arrives that the prince is inviting all the eligible young virgin girls of the region to a ball with the aim of selecting a wife. Both Elvira and Otto’s pretty daughter Agnes secure invitations, but when Agnes is caught in flagrante delicto with the stable boy, she is banished to the role of servant and Rebekka becomes determined to shape her daughter into the sort of girl that a handsome young royal would want for his bride.

While we’ve likely all seen at least one version of the Cinderella story, I’m guessing that few will have read the original Grimm fairy tale, which is altogether nastier than the more sanitised – perhaps we should say Disneyfied – film adaptations that followed. Not only does writer-director Emilie Blichfeldt draw heavily from Grimm, but she also reinvigorates a familiar tale by telling it from an unfamiliar angle and making the two stepsisters sympathetic figures. What unfolds is a biting commentary on what women feel pressured to endure to conform to societal expectations for beauty, which here takes the shape of the sort of anaesthetic-free surgical procedures that will have even hardened horror fans wincing, not least because they feel so horribly grounded in reality (it probably doesn’t help that I’ve experienced one of these operations, albeit under anaesthetic and with a plaster rather than metal cast attached to my hooter). But even that is small potatoes when compared to what Elvira is willing to do in order to make the slipper dropped by Agnes/Cinderella at the ball fit her oversized foot. Seriously, I have a long standing love of body horror cinema, and I delighted at every grotesque turn in Coralie Fargeat’s similarly themed The Substance, but there were moments here when, for the first time in many a long year, I was hiding behind my yanked-up pullover in horrified disbelief at what Blichfeldt was portraying in such wincingly realistic detail. Yet as a dark fairy tale it’s a thing of gothic wonder, with superb performances from Lea Myren as Elvira, Ane Dahl Torp as Rebekka, Thea Sofie Loch Næss as Agnes, and Flo Fagerli as Elvira’s loyal younger sister Alma. I’m already excited for the upcoming Second Sight special edition UHD release.

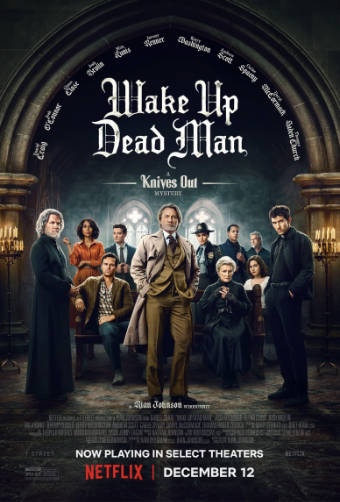

WAKE UP DEAD MAN

Writer-director Rian Johnson’s 2019 Knives Out was an unexpected joy, an Agatha Christie style murder mystery with a twisty plot, a colourful collection of characters hiding guilty secrets, a starry cast, and a script whose smarts were matched at every turn by its wit. It also marked the debut of Daniel Craig’s glorious Benoit Blanc, a dogged investigator whose southern American accent prompts one character to describe it as a “Kentucky Fried Foghorn Leghorn drawl.” So popular was this character that Johnson brought him back in 2022 for Glass Onion, which had its share of detractors but which I enjoyed immensely and for some was even more fun than its predecessor. Now we have the hotly anticipated third film in the series, Wake Up Dead Man, which like its immediate predecessor was also saddled with the A Knives Out Mystery subtitle (which does not appear on the film itself), a marketing requirement that irritated Johnson but that we’ve all learned to live with, even though it should by rights be a Benoit Blanc Mystery.

This third entry may not have the came-out-of-nowhere freshness of the first, but in other respects is every bit its equal and, in some ways, may be the best of the three. Taking acknowledged inspiration from the “impossible murder” locked room mystery scenarios outlined in John Dickson Carr’s The Hollow Man (which is name-checked in the film), the plot revolves around former boxer turned priest, Father Jud Duplenticy, who is reassigned to a small parish led by Monsignor Jefferson Wicks after punching an obnoxious Deacon, a man that even the church hierarchy secretly believes had it coming. The kindly and sympathetic Jud soon comes into conflict with Wicks due to the latter’s congregation-clearing fire and brimstone preaching and his deliberate attempts to wind Jud up, and when Wicks is inexplicably murdered during a brief break in one of his sermons, local suspicions falls instantly on the young newcomer.

One thing that Wake Up Dead Man confirms beyond doubt is that Johnson knows how to fashion a belter of a screenplay, which while a whisper more serious in tone here than its predecessors is every bit as impeccably structured, witty and character oriented. It’s this focus on character that ensures the film fully justifies its two-and-a-half hour running time and allows Johnson to incorporate some nicely judged social and even theological commentary, giving non-believer Blanc full range to dismiss the very idea of a higher religious power in an impassioned speech that has pure logic at its core, but also presenting Jud as a genuinely compassionate man whose innate kindness and commitment to his cause is tied to his sincere religious belief. At a time when disgustingly hypocritical right-wing grifters across the western world are claiming to be living by the teachings of a man they would imprison and deport if he showed his face today, Father Jud is a reminder of what the whole concept of Christian compassion and forgiveness is supposed to mean, and I’m saying that as someone whose views on religion align with completely with Blanc’s.

Once again, Johnson has assembled a cast and a half here, one that includes Glenn Close, Josh Brolin, Mila Kunis, Jeremy Renner, Kerry Washington, Andrew Scott and Jeffrey Wright, and of course, Daniel Craig as a slightly more hippyish than before Benoit Blanc. For me, though, the film really belongs to Josh O’Connor, who convinces completely as the troubled but deeply sympathetic Father Jud, marking the second year in a row when a film in which he stars has made my favourites list, following his enigmatic turn in last year’s La Chimera.

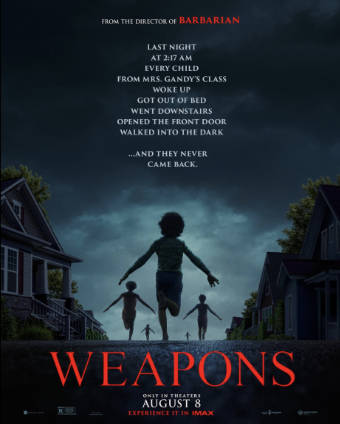

WEAPONS

At precisely 2.17am one morning, every child except one from the same school class gets up, goes downstairs, and runs out into the night, their arms held out as if preparing to fly. Where could they have gone, and what possible explanation could there be for their coordinated exodus from their family homes? As instant hooks go, this is a peach, an opening scene mystery that proves as bemusing for the townsfolk as it is for us as intrigued viewers, one that both we and they are almost challenged to solve, and when the answers come, they prove absolutely worth the wait.

It’s purely through a twist of fate that writer-director Zach Creggar’s 2022 Barbarian didn’t appear on any of my pick-of-the-year lists, having been released in the UK at the tail end of 2022 but not seen by me until midway through 2023, the one year I decided not to compile such a list in favour of marking this website’s twentieth anniversary. And had I made a list that year, you can bet the farm that Barbarian would have been on it for a whole range of reasons, from the sly casting of Bill Skarsgård in a role that proves to be not at all what it seems to the initially disorientating mid-film switch that eventually dovetails neatly into the dark developments of the first half. Damned good though that film was, Creggar’s follow-up is in a whole different league, a beautifully constructed and often witty work that tells story from multiple perspectives, rewinding time to present developments from alternative viewpoints, drip-feeding clues and plot details, and revealing the reason for actions that previously seemed random and inexplicable. The acknowledged influence of Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia is evident in the name-chaptered viewpoint switches and the range of characters, and the casting is spot on, with standout turns from Julia Garner, Josh Brolin, Benedict Wong, Alden Ehrenreich and Austin Abrams. But stealing the film by a long yard, despite not making her official entrance until after the halfway mark, is Amy Madigan as the most unexpected, offbeat, entertaining and ultimately scary antagonist you’ll find in a film all year. It’s a glorious turn in a sublimely executed melding of genres where the mystery is laced with scenes of genuine tension that are punctuated with moments laugh-out-loud humour.

And that’s it for 2025. Not for the first time I’ve wondered how much longer I can keep the site going, as my short-term memory and energy levels start to fade and life increasingly takes turns that are frankly more important to me than writing about movies, no matter how much I may enjoy the process. Maybe I have another year or two in me, I’ll have to see, and if I elect to leave work this summer I should have a bit more free time, though don’t hold your breath for reviews in March, when a much needed trip to Japan with my partner will hopefully take me away from the mounting horrors of life in a world where a madman holds sway. Now, at long last, it’s time to get back to my disc reviews. So stay safe out there, and to those in America standing up to the immoral actions of your government and the ICE thugs roaming your streets, I salute you all. Vive la revolution!