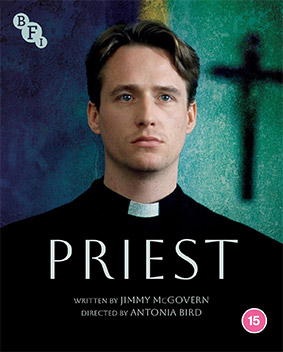

Priest

Written by Jimmy McGovern and directed by Antonia Bird, the controversial drama PRIEST is released by the BFI on Blu-ray. Review by Gary Couzens.

Liverpool. When Father Ellerton (James Ellis) has an apparent breakdown, transporting a crucifix across the city, including on a bus, and using it to smash a church window, his replacement is a young priest from down south, Greg Pilkington (Linus Roache). Greg is eager to make an impression, sometimes clashing with his colleague Father Matthew Thomas (Tom Wilkinson). He’s judgemental about Matthew’s affair with their housekeeper Maria (Cathy Tyson), despite his vow of chastity. But there’s more to it than that: Matthew wants to marry Maria but she won’t let him as that would involve giving up the priesthood. However, Greg has a secret of his own: one evening he takes off his priestly clothes, puts on a leather jacket and heads off to a gay bar, where he meets Graham (Robert Carlyle). Meanwhile, in confession he is told by fourteen-year-old Lisa Unsworth (Christine Tremarco, actually sixteen or seventeen at the time of filming) that she is being sexually abused by her father (Robert Pugh), something Greg can do nothing about due to his being bound to silence by the seal of the confessional.

Priest is a film which crossed a few lines: a serious film on a religious subject which fell foul of the established church because of some of its content, and not least its critical attitude towards said church. It’s clearly a personal project for writer Jimmy McGovern, who was raised Catholic. (As was I, also going to a Catholic secondary school – as Graham says to Greg in one scene, it takes one to spot one.)

I’ve mentioned Jimmy McGovern, writer of this original screenplay. There’s a tendency in film reviews to attribute the film to its director, and while Antonia Bird’s contribution to Priest is considerable, I’d suggest this is a writer’s film. And while it tells a compelling story – despite its dark theme, often funny too and finally very moving – it doesn’t fail to take aim at the Catholic Church. It has in its sights the vow of chastity and its effect on the men who take it (straight or gay alike), and not least the seal of the confessional which allows evil to flourish. Yet not once is the film anti-religious. In fact, one major subplot is resolved by what the film implies is divine intervention. That scene is so powerful that it almost overwhelms the rest of the film, which (as I’d forgotten, seeing the film again for the first time since its cinema release in 1995) has at this point just over half an hour to go. One way in which the film is so effective is that characters are given their reasons, even if they are loathsome. This includes the skin-crawling scene where Mr Unsworth uses the confidentiality of the confessional to not only boast about committing incest but giving a historically-sourced rationale for it, implying that it’s something any man would do if they simply had the balls to (paraphrasing). While this is a subplot, it provides the film with its ending and catharsis.

Antonia Bird had directed on the stage and on television, and this originally television-intended film (made for BBC2’s Screen Two strand) was her first to have a cinema release. More about her career in the discussion of the extras below, but she made four cinema features in all, following Priest with Mad Love (1995), Face (1997) and Ravenous (1998), before returning to the small screen with various high-end TV movies and series for the rest of her career and life. I wasn’t alone in considering her one of Britain’s leading directors at the time, but there is a sense of unfulfilled potential, particularly given her early death from cancer. At her best, her films were tough-minded, while still working in a populist framework, strongly acted, deeply compassionate. British cinema of the 1980s and 1990s is littered with names who were able to make just one or maybe two or three features for the big screen, spending most of their careers on television: for example the late David Drury, Edward Bennett (whose Ascendancy (1983) jointly won the Golden Bear at Berlin but has vanished into obscurity since), Mary McMurray and Hettie Macdonald, who followed Beautiful Thing in 1996 twenty-seven years later with The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry. At least Bird did make those four, as well as remarkable television work such as Safe, made for BBC2’s Screenplay strand in 1993 but given a few festival screenings. Priest is her best film.

Bird’s films are always driven by their actors, and Linus Roache gives a strong performance as the conflicted Greg. There is strong support by Tom Wilkinson and Robert Carlyle and Robert Pugh is effectively vile if not actively terrifying. Further down the cast are Paul Barber (three years before The Full Monty, which also starred Carlyle and Wilkinson), James Ellis who is barely recognisable other than his Northern Irish accent as the man who played Bert Lynch in the entire sixteen-year run of Z Cars, which admittedly ended sixteen years before this. Also in the cast is Anthony Booth, with his screen son played by his real-life grandson Euan Blair, son of Cherie and Tony Blair, who in the year that Priest was made became leader of the Labour Party and three years later Prime Minister. Bird’s films usually centre on male leads – in the interview amongst the extras, she suggests that that’s what was more likely to be made – but she doesn’t forget the women in this story, Cathy Tyson and particularly Lesley Sharp as Lisa’s mother.

There are some minor nitpicks: some of the music choices are a little on the nose, such as an instrumental version of “You’ll Never Walk Alone” during the final scene. It’s a compelling film, ably containing its very serious issues in a strong drama that’s not afraid of humour. The film was contentious from the outset, with no Liverpool church allowing filming on their premises, so the church scenes were shot in Croydon. In the UK it had an uneventful release, but it was in other countries that controversy broke out. In Ireland, the Catholic Church called for the film to be banned. A decade or two earlier, it might have been, but the Irish Censor Board declined to do that, passing Priest with an 18 certificate. What happened in the USA was worse, not helped by Miramax’s admittedly provocative decision to release the film on Good Friday. The USA had a version shortened by seven minutes, with the sex scene between Greg and Graham edited to avoid the commercially prohibitive NC-17 rating, which would have restricted the film to those over that age. (The uncut version had and has a 15 from the BBFC, and to the best of my knowledge no one has complained.) The Catholic League and the American Life League condemned the film as blasphemous and organised a boycott of Miramax’s parent company Disney, calling for the film to be withdrawn. Some cinemas received bomb threats for showing it. Priest missed any Oscar attention, unsurprisingly, but it won Best British Feature at the Edinburgh Festival and the Teddy Award at Berlin. It was nominated for a BAFTA as Best British Film, though lost to Shallow Grave.

sound and vision

Priest is released by the BFI on a Blu-ray disc encoded for Region B only. The film had a 15 certificate in cinemas and retains that on disc. The feature begins with an advisory of scenes of sexual violence, harm towards children, domestic violence and abuse.

The film was shot on Super 16mm (by Fred Tammes, who had shot Safe for Bird and went on to make Mad Love and Face with her), partly for budgetary reasons, partly because it was originally intended as a television production. (If it had been made even a year or so earlier, it might well have been in 4:3, as for example another Screen Two production that received cinema distribution, Truly Madly Deeply (1990) was. But widescreen television was on the way.) The Blu-ray transfer is in the ratio of 1.66:1 and is derived from a 2K scan and remaster from the original negative. Grain is noticeable, as you would expect from its 16mm origins, but the colours seem true (from what I remember of my cinema viewing thirty years ago) and blacks solid. For technical reasons I have been unable to source screengrabs from the disc, so this review is illustrated by BFI publicity stills.

The sound is the original Dolby Digital (SR-D) mix, rendered as LCPM 2.0, which plays in surround. The surrounds are mostly used for ambience and the music score, with some direction sounds such as seagulls and rainfall. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are optionally available on the feature only, and I didn’t spot any errors in them.

special features

I Miss Those Days: An Interview with Linus Roache (17:43)

Newly recorded for this release, Linus Roache talks about his career. He was born of actor parents, but they had different sensibilities and reputations. His mother (the late Anna Cropper) was more into improvisation and had some intense roles under her belt. Meanwhile, his father, William Roache, had by then (1964) been playing Ken Barlow in Coronation Street for just over three years, so was already a star. Roache Senior is in the Guinness Book of Records for playing the same role for the longest time. As of this writing (November 2025) he has clocked up 4819 episodes and is still playing the role at age ninety-three.

Linus Roache actually appeared on Coronation Street as a child. The Internet Movie Database doesn’t record this, listing his first screen role at age twelve in an episode of The Onedin Line. In his earlier career he was primarily a stage actor, working for the Royal Shakespeare Company and the National Theatre, meeting his wife at the latter. As he wanted to be on television and in films (James Dean was an inspiration), he was told to scale down theatre commitments as they usually required long runs. His earliest television lead was as Vincent Van Gogh in an episode of Omnibus in 1990. Meanwhile, playing an IRA man in a 1989 episode of Saracen introduced him to Antonia Bird. He received the offer of Priest when he also had an offer of a London West End stage role. He has no regrets in taking the film, though one story of the production was that the kissing scene with Robert Carlyle on a freezing cold beach had to be redone because the film was damaged. His mother was proud of the role, after apparently being uncomfortable with his playing gay.

The BAFTA and BFI Screenwriters’ Lecture Series: Jimmy McGovern (27:02)

Recorded at BAFTA in 2016, Jimmy McGovern is interviewed by Miranda Sawyer about his career. He began in theatre, which he didn’t like, but it wasn’t until his thirties when he was taken on by Brookside, shortly after Channel 4 was launched. He basically learned on the job, his primary role amongst the show’s writers being coming up with storylines. He talks about various of his films and television, though not so much Priest. Some of these he was approached to do, for example Needle (1990), for BBC2’s Screenplay strand, for which he was approached by commissioner George Faber. Hillsborough (1996) was a production clearly close to his heart, having been approached by relatives of some of the dead to tell their story. He’s outspoken about the police’s role on that day, encouraged to act the way they did by being given big pay rises by Margaret Thatcher for their role in breaking up miners’ strikes. As with the later Common (2014), it’s an illustration of the difference between law and justice. He also talks about his role in the anthology series The Street and Accused, where he saw himself as a mentor for new writers, who were there to generate the stories (one a drug dealer who hadn’t written before) and would be credited even if McGovern had to rewrite their scripts completely.

Jimmy McGovern Remembers…Priest (14:23)

More McGovern, this being one of a series of ten-to-fifteen-minute introductions which BBC Four produce to accompany their archival repeats. In this case, this was for a showing of Priest on that channel on 30 April 2025. McGovern says that Priest is something he always wanted to write, as he was raised Catholic in an area of Liverpool replete with Irish Catholic names like his. At first he wrote a story about a heterosexual priest with a female partner, and the gay priest was a subplot, but eventually they swapped places. As part of his research, he met a real gay Catholic priest who clearly regarded his sexuality as a burden. Throughout his career, McGovern has set out to ask questions which need answers, and there were plenty he could ask about the church and faith he was brought up in. Despite the controversy, the film was successful, playing at the Odeon in Liverpool for four months. The gay priest he had consulted had by then moved to Blackpool, but one day he called McGovern. Not only did he like the film, he’d seen it fourteen times. McGovern considers Priest to have one of the few successful endings he has ever written.

The Guardian Interview: Antonia Bird (71:35)

Antonia Bird died in 2013 at the age of sixty-two. In 2016, BBC Four broadcast a documentary on her, From Eastenders to Hollywood, as part of a tribute evening, which included repeats of her TV film Care (2000) and her two-hander episode of Eastenders. As the title implies, with she was (along with Beeban Kidron, whose To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar was made around the same time) the first British woman to direct a film for an American major studio. From Eastenders to Hollywood would have made an excellent extra for this release, but I suspect that having to license all the TV and film clips in it made it unviable. Instead, we have this interview with Diana Quick from 1995. Presented from a rather rough videotape source (with occasional tracking lines), but better this than not at all, the interview with Diana Quick took place at the then National Film Theatre in 1995. I was in the audience.

The conversation was structured around several extracts from Bird’s work: a selection from her television work (Casualty and Eastenders included), plus Safe, Priest and Mad Love. As usual for these extras, these clips have been edited out for licensing reasons, but you can get the gist of them from Bird and Quick’s discussion. There are questions from the audience – not always clear in this recording, but Quick and Bird do summarise some of them.

Bird began her career in theatre, at the Royal Court. One play she directed there, Tom McClenaghan’s Submariners, was seen by longtime television producer Innes Lloyd, who bought the rights and fought for Bird to direct the television version, which she did in 1983. After that, forever, she was turned down by both the BBC’s directors’ course and film school, but was assisted by Julia Smith (television producer and director and co-creator of Eastenders) after she wrote to her. And so her next directing credits were on the soap, for which she directed eighteen episodes in all, in 1985 and 1986, plus five in the first two series of Casualty (1986 and 1987). She was the first woman to direct an episode of Inspector Morse. Bird directed a lot of what she calls “boys’ stuff”, such as Saracen and the five-part serial The Men’s Room (1991). She says that it’s important to do work that you believe in – there was one where she didn’t (she doesn’t name it) and regretted it.

Safe was a breakthrough, made in 16mm for the BBC Screenplay strand, winning the BAFTA for Best Single Drama and showing to acclaim at the Edinburgh Festival, winning the Best First Film award. After the clip is shown, Bird apologises to Kate Hardie, as the clip breaches her “tit for bollock” policy on screen nudity – basically, if she has to take her clothes off, so does he. What comes out from this interview is how much Bird achieved due to the compromises she had to make. She was unable to shoot either Safe or Priest in 35mm as she would have liked, and both films were cut down from the version she delivered. Safe was written and made as an eighty-minuter, but BBC’s slot was only sixty-five minutes, so it had to be shortened. Likewise, Priest lost about ten minutes (and was edited further in the USA). Bird says that she was looking to restore Safe to its full length, but sadly this never happened.

Priest was a script sent to Bird by producer George Faber, and it was her enthusiastic response which enabled him to have the film made. At first, the BBC wouldn’t allow it to have big-screen showings – it had one at Edinburgh, and then at the Toronto Film Festival, and the strong reception it received had enabled its cinema release. When it was released, Bird was making Mad Love (a 35mm film for Disney, why wouldn’t she?) but again what reached the screen was compromised: made as an R-rated film and heavily re-edited to achieve a PG-13, with, Bird says, some of the best sequences on the cutting-room floor likely never to be seen again.

Bird also talks about how she likes to employ women on her productions, as long as they were good enough of course. She also talks about liking to work in different genres, as her next film would be a gangster picture – which turned out to be 1997’s Face.

The Take: Priest (3:49)

A short piece made for the BBC in 1999 where Simon O’Brien looks at Priest and reflects on how McGovern’s childhood experiences inform it. He also interviews Linus Roache, who particularly highlights the sequence which, as I suggest above, implies divine intervention.

The Priest (22:05)

An amateur documentary from, according to the BFI, 1953, though a letter we see on screen has a 1954 date. Made in the Brentwood and Romford areas, it’s explicitly intended as a recruitment tool for the (Catholic) priesthood. It begins with some statistics. A hundred years earlier, the population of the UK was eighteen million, of which 700,000 were Catholics, of which 250,000 were practising. To serve this flock were 600 churches and chapels and 700 priests. Now (that is, in the mid 1950s), the population is forty-five million, of which five million have been at least baptised as Catholics and three million practise the faith, for which there are 6500 priests, 4000 of them secular. So, says the documentary, we need more priests. The rest of the film is a run-through of what a candidate to the priesthood can expect, after some six years of training. They would be expected to celebrate two or even three masses on Sundays or holy days. Chapels are needed in remoter areas, which may later become parishes in their own right, once accommodation for the priest has been arranged. Some priests have to travel around their parishes, saying masses in non-ecclesiastical locations, so some of the flock get to celebrate mass about six to eight times a year. We see a priest baptising a premature newborn in an incubator, in a hurry as the baby is not expected to live. At the other end of the age range, a priest is called out at night to give the last rites. Despite the busy schedule, relaxation (such as golf) is necessary for “an evenly-balanced mind”.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, with the first pressing of this release, runs to twenty-eight pages plus covers. After a spoiler warning, it begins with “Him Who is Without Sin” by Lillian Crawford, beginning with a quote from St John’s Gospel from which the essay title is derived. Crawford discusses the genesis of Priest, originally considered as a storyline for Brookside, then part of a ten-episode series inspired by the Ten Commandments (influenced by Dekalog, maybe?) then a three- or four-part serial on homosexuality in the Catholic Church, then the feature-length film it ended up as, commissioned by the BBC following McGovern’s success with the ITV series Cracker. It was trailed as “Jimmy McGovern’s Priest”, but Crawford highlights Antonia Bird’s contribution. Bird did rework McGovern’s script, and Crawford suggests that the various issues in the film are “the provocations of a male enfant terrible” and that Bird’s direction makes them “emotionally impactful upon realistic lives”. Crawford does highlight that Priest benefited from the BBC’s willingness to deal more with gay issues in drama, following criticism of its lack of coverage of same in current affairs. Although there were certainly gay-themed dramas on the BBC going back at least as far as Daniel Massey’s self-hating character in The Roads to Freedom in 1970, it’s doubtful that the sex scene between Greg and Graham could have been included in anything made much earlier than it was.

This is followed by “Political, Pragmatic, Popular: Antonia Bird’s Cinema of the People” by Rachel Pronger, which as the title implies is an overview of Bird’s work. Pronger begins by quoting Bird from the Guardian Interview elsewhere on this disc that as of 1995, Bird thought she was at a crossroads, undeniably successful but looking to find a halfway course between small issue-based indies and big-budget Hollywood productions. Pronger suggests that after Bird’s early death, she hadn’t had the recognition she was due and she was likely to vanish from sight. The result of this was a BFI retrospective in 2016 and the From Eastenders to Hollywood documentary referred to above. Pronger suggests that Bird’s quality lay in mixing “firebrand politics” with a populist sensibility, leading her from the Royal Court, frequented by “middle-class intelligentsia” to the mass-audience medium of television and later cinema. In the latter medium, she was less arthouse than contemporaries such as Lynne Ramsay, Clio Barnard and Andrea Arnold and as such was often associated with work with male leads – the pragmatic side of the title, given that they were more likely to be made. She also prioritised the actors on her productions, especially given that she was the daughter of one (Michael Bird). However, her socialist politics was another barrier (along with her gender) and George Faber believed that she was blocked by some people for that reason. However, Pronger suggests, her studies of troubled masculinity and her vision of television as a site of political awakening, remain prescient today, more than a decade after her death.

This profile of Antonia Bird is followed by “The Angry Compassion of Jimmy McGovern”, by Mark Duguid, author of a BFI TV Classics monograph on Cracker. This covers the writer’s life and career from his childhood in Liverpool to his breaking into television on Brookside in 1982, soaps and children’s drama by then having replaced low-budget single dramas as training grounds for writers. (Also writing for Brookside at the time were Frank Cottrell Boyce and the late Kay Mellor.) His Catholic background is reflected in his storylines for the Catholic Grant family. He left the series after they cut a scene where a character burned a copy of The Sun with its infamous “The Truth” headline about Hillsborough – something which was very far from the truth and provoked a boycott of the newspaper in the city. The Hillsborough disaster inspired a storyline in Cracker, and after that the eponymous 1996 drama. Another drama-documentary was 1999’s Dockers, about Liverpool’s dock dispute which lasted two and a half years. Duguid highlights McGovern’s maintaining the television tradition of single plays in the series The Street (2007-2009) and Moving On (2009-2023), working with newer writers, something he also did in Australia for the series Redfern Now (2013), about the aboriginal community in the Sydney suburb of the title. He returned to the UK with another anthology series, Accused (2010-2012). As Duguid points out, McGovern’s work is not always easy viewing, but always containing compassion and humour, with some sense of redemption. That’s still the case in his mid-seventies.

Following a cast and crew listing for Priest, the booklet has credits for and notes on the extras, plus plenty of stills.

final thoughts

While controversial on its release, in the USA and Ireland especially, thirty years later Priest now looks like, not just among its writer and director’s best work, one of the major British films of its decade. It’s well-served by this BFI Blu-ray release.