Here’s looking at you, kid

A young woman starts to fear that a traumatic incident from her childhood is causing her to lose her mind in the 1974 Italian psychological thriller THE PERFUME OF THE LADY IN BLACK [IL PROFUMO DELLA SIGNORA IN NERO]. Gort discovers that paranoia can be justified on Indicator’s superb new UHD.

Silvia (Mimsy Farmer) is an industrial scientist who lives alone in a gloriously designed and located apartment building in Rome, and she and her team are currently busy working on some sort of chemical MacGuffin that is facing an imminent deadline. On her way home from work one day, she stops by the cemetery to lay some flowers on her mother’s grave and experiences a moment of reality disassociation in which all birdsong ceases to be replaced by the sound of an oddly ominous and physically non-existent wind. Back at home whilst preparing to head out for the evening, she is visited by her immediate neighbour, Signor Rossetti (Mario Scaccia), who is looking to borrow some tea. She appears to be on friendly terms with the older man, despite the fact that he initially comes across as a creepy old pervert, invading her personal space and peering into her bedroom with a lascivious grin. Sylvia is unfazed but makes her excuses anyway as she has a date with her boyfriend Roberto (Maurizio Bonuglia), a self-satisfied twerp whom she seems mysteriously fond of but who clearly expects her to jump to whatever tune he chooses to whistle.

The date in question sees Silvia and Robert having drinks with three friends, one of whom, African university professor Andy (Jho Jhenkins), initially had me gearing up to make allowances for archaic racial stereotyping with his foreboding speech about the witchcraft and cannibalistic rites of his people. Then, just as this peaks, he roars with laughter and assures the startled Sylvia that everything he just told her is nonsense and that no such magical tomfoolery is practiced today. This is despite Roberto’s story of what happened to a member of his party who came in to conflict with a local witch doctor on a visit to Cameroon. Is any of this relevant to what will later unfold? Could be.

When Roberto drops Silvia off at home at the evening’s end, their goodnight kiss is observed from an apartment window above by Silvia’s friend, Francesca (Donna Jordan), who just stops short of licking her lips at what she sees. Robert makes his excuses for not coming in with Silvia as they have to get up early for a scheduled game of tennis with Andy. He then loses his rag when Silvia reminds him that she won’t be coming because she has some material to check at work tomorrow in order to meet an important deadline. “The hell with the material!” barks the insensitive prick, then snapping, “It’s as if you had an obsession about winning the Nobel Prize!” I think he’s confusing her with Donald Trump. The dejected Silvia thus heads indoors to get some sleep, and it’s after this that things start to get a little strange.

Silvia is woken the next day by a fearsome-looking woman named Carlotta (Aleka Paizi), whom I presume is the apartment building manager. If not, then I’d sure like to know how she is able to open Silvia’s locked front door without booting it down. It turns out that it’s not early morning as Silvia expects but late afternoon, and she’s still dressed in her clothes from the previous evening. Curiously, a treasured framed photo of her and her late parents is lying on the floor with the glass in shatters. How did this happen? It’s never explained, but when Carlotta points it out, the still sleepy Sylvia replies sharply, “I know. I broke it.”

When she heads out, Silvia calls at an art shop to drop off the photo to be reframed. As she does so, she is watched by the sort of man you’d employ to guard the door if you wanted to keep even the most terrifying drunk from entering a nightclub. Just moments after Silvia has departed, the man nips into the shop to have a chat with the clerk. We don’t hear what they say, but the inference is clear. Silvia then meets up with Francesca and the two visit a shop that Silvia has never noticed before that sells exotic curios. Here, Silvia buys a framed blue butterfly as a present for Roberto, who frankly deserves a present about as much as I deserve to be wooed by Emma Stone. Whilst in the shop, Silvia is once again secretly observed, this time from behind a backroom curtain by a figure whose identity we won’t discover for a while.

When Silvia pops round to see Roberto that evening, she finds his doors and windows open but no sign of Roberto himself. There’s an unsettling atmosphere that clearly rattles her, which peaks when she turns to see her long-dead mother reflected in a mirror, dressed a polka-dotted black dress and spraying herself with perfume, a justification for a title that otherwise has no real bearing on what unfolds. Silvia screams, and that’s the moment that Roberto enters, and in that way that men always seem to have in genre movies, he dismisses her claim as the product of over-tiredness.

If it seems as if I’m laying out the whole plot in detail, know that at this point director and co-writer (with Massimo D’Avak) Francesco Barilli is still on the narrative starting block, setting up the story and signposting the strange developments to come. These include a decorated vase that Silvia sees displayed in a shop window that is an exact duplicate of one that her mother used to own. When she later returns to the shop it is no longer visible, and the proprietor swears that they’ve never stocked such a vase. The next day, however, a parcel is left for Silvia at the apartment building reception containing the vase is question and a blank message card. She’s only just unwrapped it and placed it on a table when Francesca pops round bearing surplus flowers that she is looking for a home for, which she pops straight in this attractive new receptacle. That evening, however, all of the plants have mysteriously shed their petals. Starting to sound complicated? You don’t know the half of it. The sight of the vase triggers some unpleasant memories for Silvia, transporting her back to a dark moment in her childhood when she walked in on her mother having sex with a brutish individual (Orazio Orlando), whom the sharp-eyed may recognise as the man who was secretly observing her at the art shop. And then there’s the strikingly shot scene in which Silvia’s so-called friends convince her to be read by blind medium Orchidea (Niké Arrighi), whose alarmed response and potentially revealing words send the distressed Silvia running from the room. And just what is it about the untimely death of Silvia’s mother that continues to haunt her now adult daughter? Might the then young Silvia have been directly responsible?

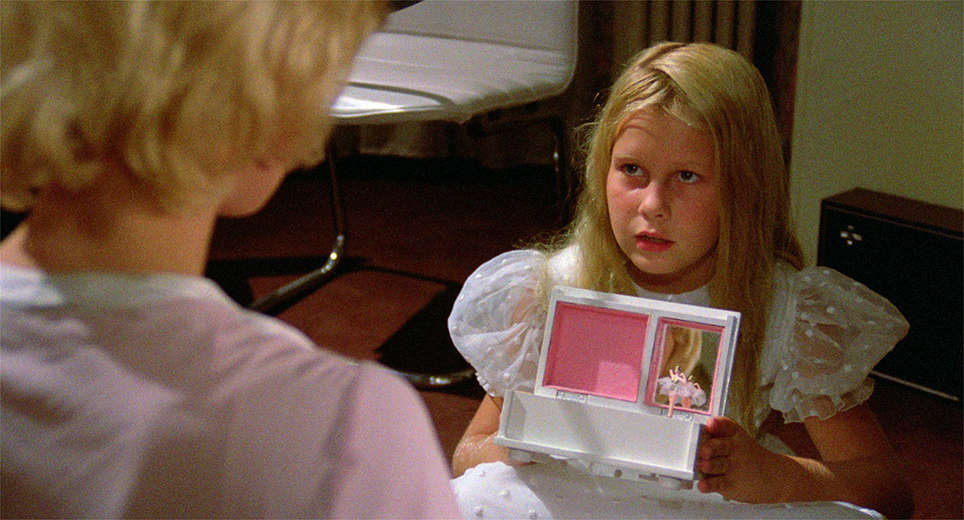

It doesn’t end there. Almost everywhere Silvia goes, seemingly incidental people observe her in the manner of undercover cops preparing to spring a trap on an unknowing suspect. She clearly doesn’t know them or even notice them, but they sure seem to know her. Then there’s the aforementioned date to play tennis with Andy, which we are left to presume that Roberto browbeat Silvia into keeping after all. Here, Silvia’s hand is pierced by a nail that’s mysteriously been driven though the handle of a racket. With Robert off grabbing a drink with Francesca (well of course he is) and Silvia freaked out by the sight of blood, Andy responds by taking her hand and sucking on the wound whilst staring at her in a manner that suggest this is some sort of vampiric foreplay. This alarms and disorientates Silvia, whose attention is then drawn to a young girl playing in the field behind the court, a girl who later reappears at Silvia’s door, strides into her apartment, and acts as though she’s lived there her whole life. Then, just when I’d settled on dismissing Roberto as nothing more than an insensitive arse, he phones Silvia to tell her he’s too caught up in work that evening to keep an arranged date, then gets into a car in which Andy and an old man we later learn is the apartment building’s caretaker Luigi (Ugo Carboni) are waiting. Where to they drive off to? It’s hard to say, but later we see Andy accompany Orchidea to a secret entrance to a cavernous lair in which they don lab coats and join a hoard of other similarly dressed individuals we’ve seen earlier and head down in to the railway-sized tunnel ahead for flip knows what.

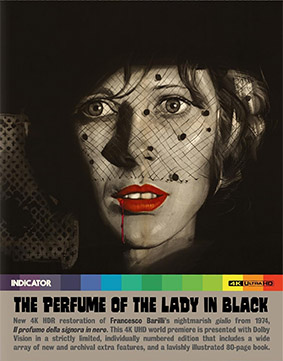

If all this sounds overly mysterious and perhaps a tad confusing then I’ve accurately conveyed how the first viewing of this film left me feeling, although I will freely admit that this was partly down to incorrect assumptions on my part about what I was about to see when I popped the disc into the player. It’s an Italian genre film from the 1970s, and my conviction that this was to be a prime slice of Italian giallo had been initially sparked by a deceptively innocuous title that would seem to place it alongside the likes of A Black Veil for Lisa [La morte non ha sesso] (Massimo Dallamano, 1968), The Bird with the Crystal Plumage [L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo] (Dario Argento, 1970) and The Bloodstained Butterfly [na farfalla con le ali insanguinate] (Duccio Tessari, 1971). And take a look at that picture on the cover of the UHD of an attractive woman wearing a black funeral veil, bright red lipstick and a startled expression, with blood trickling from the corner of her mouth. Come on, it has to be a giallo, right? Well, for the most part, no it’s not, at least not in the sense us genre fans have come to expect. It becomes one, sure, but not until the final 15 minutes, which I can’t discuss without delivering an elephant-size spoiler. I will be dropping small hints, but with a warning beforehand for newcomers when I’m about to do so.

So if The Perfume of the Lady in Black [Il profumo della signora in nero] is not a giallo, what exactly is it? Well, if I had to slap a label on it, then psychological thriller would probably suit as well as any. Of course, as that’s not what I was expecting it to be going in, I found myself subconsciously wondering when the killing would start and becoming just a little confused when it failed to do so. Lots of peculiar things were happening with little in the way of explanation, and when that explanation came, I was still left scratching my head. It almost felt as if Barilli was just throwing in elements purely because he could make them seem spooky.

Then I watched it again and all of that changed. Once you know where it all leads, seemingly random elements no longer feel random at all but carefully planned and intricately connected. That said, Barilli still invites his audience to connect a few dots, and sometimes even interpret elements that he elects not to clearly explain, which frankly proved part of what made the film so much more engrossing for me the second time around. I should also note that while I first watched the English language version of the film, I switched to the Italian language track for the second viewing, and this genuinely altered how I felt about one crucial aspect of it. Time, I guess, to talk about the performances.

It’s been noted several times before on this site that Italian genre films of the 60s and 70s were usually filmed without synchronised sound and post dubbed in Italian for domestic distribution and in English for the international market. This allowed Italian filmmakers to use actors from a variety of countries and have them deliver their lines in their native language rather than bluff their way in Italian. Depending on the quality of the subsequent dubs, this can have a distancing effect, bringing an artificial edge to otherwise solid performances because of a disconnect between the actor and the voice they’ve been gifted in post-production. Even when the actor is dubbing themselves, standing in a recording booth reciting lines is very different to delivering them on set or on location, where you have the other actors to address and respond to.

Although an Italian production with a largely Italian supporting cast, actors Mimsy Farmer and (I think but have been unable to confirm) Jho Jhenkins hail from America, young Lara Wendel was born in Germany, and Niké Arrighi is French. With so much of the film centred around Silvia, the English dub would seem to be the logical way to go, but although Mimsy Farmer apparently dubbed her own voice here, her vocal delivery is sometimes lacking in emotion, which has the effect of making her performance feel – how can I put this? – a little stilted in places. Switch to the more expressive Italian track, however, and it’s a different story, as this feels more in-keeping with how the lines were probably delivered on location and makes it easier to appreciate the impressive restraint of Farmer’s performance. When things take a serious turn in the later stages, she gets a chance to really shine in whichever version you choose to watch, notably in (spoiler ahead) a punishing sequence involving either rape or an attempted rape, depending how you read it, one that may be real or a hallucination or Silvia reliving a traumatic childhood memory, or perhaps even a combination of all three. See what I mean about Barilli leaving things open to audience interpretation?

In an otherwise enjoyable supporting cast there are a couple of moments that seem spectacularly wooden where this lack of expressiveness is shown to have purpose. When Andy is telling Silvia about the ancient cannibalistic rites of the African people, for example, he genuinely looks like he’s reading words that have just been written from a card being held up for him off camera, but when he reveals that he has just been winding Silvia up it becomes clear that this was all part of his spooky storytelling act. And when Silvia screams after seeing the vision of her mother, I almost laughed out loud at the complete lack of emotion in Roberto’s response, but watch the whole film and this makes complete sense.

The key influences are not hard to spot and are primarily Roman Polanski, specifically the 1965 Repulsion and the 1968 Rosemary’s Baby. The focus of the former is a young woman who is slowly losing her mind within the confines of her apartment, while the latter is a tale of an apartment-dwelling woman whose neurosis and paranoia may well be the result of a genuine conspiracy. Both are at play here, but while some later events may well be the product of the increasingly troubled Silvia’s imagination, the decision to show her being observed by people that she does not even notice removes any ambiguity in the early stages, and once Roberto and his chums head off to their mysterious tunnel meet, we know for sure that there really is some sort a conspiracy against her. There are clues to its nature dropped in the early stages that I, for one, didn’t recognise as such until my second viewing. Recognising those early signals for what they are also helped me to make better sense of a final scene in which the film dives head-first into genuinely jaw-dropping grand guignol horror, but which seemed to come almost out of nowhere the first time around. Even then (spoiler ahead, skip to the next paragraph to avoid), Barilli leaves it to the viewer to rationalise how people that you’ve just watched being brutally murdered are then shown to be alive and in good health with no sign of injury. I have my own theory on this, and whether or not you can formulate one yourself that makes sense within the logic of the film will likely have an impact on your response to it.

It’s fair to say that Francesco Barilli is no Roman Polanski, and The Perfume of the Lady in Black never hits the considerable heights of the two films from which it draws influence. Yet that shouldn’t take away from what Barilli achieves, infusing even theoretically innocuous moments with a sense of real danger and dread. It’s hard to underestimate the work here of cinematographer Mario Masini and composer Nicola Piovani, with Masini’s use of pastel colours, low-key lighting, occasionally striking compositions (the best of which I can’t describe without dropping spoilers) and smoothly drifting dolly shots transforming everyday locations into pits of discomfort and potentially sinister threat, which is given a serious boost by Piovani’s consistently excellent and unnerving score. Given that this was former TV director Barilli’s first theatrical feature, it shows remarkable confidence and a clear understanding of the possibilities offered by the medium. It may not lay out every turn of the plot on a platter, and as a viewer you will have to do a bit of sometimes imaginative dot connecting, but this is still a largely understated, tightly structured, stylishly executed and increasingly unsettling psychological thriller with (possibly) supernatural overtones and an absolute belter of a final scene. It also reminds us that just because person exhibits paranoid behaviour, that doesn’t mean there are not people out to get them.

sound and vision

The accompanying booklet states:

The Perfume of the Lady in Black was scanned in 4K at Augustus Color in Rome using the original 35mm negative. 4K HDR colour correction and restoration work was undertaken at Filmfinity, London, where Phoenix image-processing tools were used to remove many thousands of instances of dirt, eliminate scratches and other imperfections, as well as repair damaged frames. No grain management, edge enhancement or sharpening tools were employed to artificially alter the image in any way.

Not to be hyperbolic, but the resulting 2160p, 1.85:1 framed transfer on Indicator’s UHD release is downright glorious. The image is sharp, small details are impeccably defined, and the contrast balance is consistently sublime, with solid black levels, excellent shadow detail, and no hint of burn-out on the highlights. And oh, the colour! The pastel hues of Mario Masini’s gorgeous cinematography have been beautifully reproduced here and sing from the screen, doubtless due in no small part to the Dolby Vision HDR. It’s something that really doesn’t come across at all in the distinctly non-HDR screen grabs here. Dust spots have been eliminated, a fine film grain is visible, and the image sits consistently solidly in frame. Seriously, this is one of the most impressive 4K UHD transfers I’ve seen since I first embraced the medium.

Both the English and Italian soundtracks have also been restored and are presented as DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono tracks. It should come as no surprise that there are some limitations in the tonal range, but both tracks are otherwise in good shape, with clearly audible dialogue, solid presentation of Nicola Piovani’s marvellous score, and no obvious traces of damage or wear.

Optional English subtitles kick on by default on the Italian track, and optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available on the English language track.

special features

Audio Commentary with Eugenio Ercolani, Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson

A trio of commentators who are all fans of what Ercolani describes up front as one of the most elegant and refined giallo of its time (only to have Howarth immediately suggest that it’s not a giallo at all) deliver a solid and engaging examination of the film and its makers. It certainly helped me to clarify my own theories about just what is going on beneath the surface narrative. They note the Polanski influence and suggest that also anticipates the director’s 1976 The Tenant, and provide info on the film’s development and release, the locations, the critical reception, director Francesco Barilli, cinematographer Mario Masini, composer Nicola Piovani, and many of the actors. They reveal that the title is borrowed from an unrelated 1906 novel by Gaston Laroux, make some interesting points about the chosen colour palette, and explore the links to Alice in Wonderland. It becomes clear that Ercolani really hates Roberto Benigni’s Life is Beautiful, and in the process of praising Mimsy Farmer’s performance, they at one point claim that there was no-one else who could have pulled this role off. Eh? Wait, you’re seriously suggesting there were no other young actresses working in the early 1970s who were as skilled at their craft as our Mimsy? Hang on, I’ll just grab a pen and write you a list. That aside, an informative and consistently interesting companion to the film.

Francesco Barilli: Exploring Beauty (19:59)

A newly shot interview with an ageing and clearly unwell Barilli, who nonetheless manages to be consistently interesting and even witty at times, despite sometimes struggling to maintain his posture and find his words. He entertainingly traces his journey from directing television (“TV was fun, but I didn’t belong there”) to making his first feature, notes that both the script and the choice of technicians should be bomb-proof on any production and claims that “I’ve always had a delightful rapport with the actors, as long as they are not morons.” He discusses what he describes as a “beautiful” final scene and even makes a witty remark about its content that I absolutely cannot reveal here. It’s the same story when it comes to what he made a grip on the film do in the final scene when he discovered that the man was a fascist. When asked about directing today, he rather sadly retorts, “I don’t give a shit about directing any longer. I’m fed up. Because it’s pointless and vain.”

Francesco Barilli: The Death of Cinema (16:05)

An earlier interview with a healthier Barilli, shot in 2015 for Minerva Pictures and edited for this release by James Blackford, in which he recounts his journey from a 15-year-old who shot uncompleted serial killer movies on Super 8 to becoming the director of The Perfume of the Lady in Black. There is some crossover here with the above detailed interview when he talks about how the film came about, and he does openly acknowledge that he was inspired to reshape the script into its final form after a viewing of Rosemary’s Baby. The title of this piece comes from Barilli’s pessimism over the then current state and potential future of Italian cinema, where no-one makes horror or noir features any more, preferring instead to make family friendly movies that will play well on TV. In a comment that genuinely warmed my heart, he says at one point, “Who wants to make a ‘nice’ film?” Absolutely, sir.

Francesco Barilli: Portrait in Black (24:26)

The trip back in time continues with this 2004 interview with an even more lively and animated Barilli about the making and release of The Perfume of the Lady in Black, much of which you will have already heard if you’re watching the special features on this disc in their reverse-chronology menu order. We do get more on the casting of the lead roles, the links to Alice in Wonderland (“Alice is completely insane and surrounded by insane people”), and the psychology of the character of Silvia, and once again there’s a fair amount about the final scene. “The best thing for a director is to find a good script ready to go,” Barilli says at one point, only to the muse on the near impossibility of such an event actually occurring.

Lara Wendel: The Memories of the Lady in White (11:23)

Actress Lara Wendel, who is credited in the film as Daniela Barnes and who plays the little girl whose identity I’ve tactfully avoided revealing, recalls how she got into acting in Rome, first in commercials and later in features, before moving on to The Perfume of the Lady in Black. She has a story about having to have her hair dyed for part and the attention it created at school the next day, remembers that Mimsy Farmer was sweet to her but not big on conversation, and reveals that an adult body double was used when required and that dialogue in her scenes had to be changed if was deemed inappropriate. She also admits that while she’s very comfortable in front of the camera in movies, she’s a lot less so in interviews, which is doubtless why this one is audio only and runs under still images and clips from the film.

Stephen Thrower: The Profumo Affair (34:19)

Author, musician and hugely knowledgeable horror enthusiast Stephen Thrower opens this interview by echoing my own thoughts when he notes that the title makes The Perfume of the Lady in Black sound like giallo, but that it’s actually a psychological horror with a few giallo elements. He also suggests that it develops into a supernatural horror, and whether it does or not is, I believe, one of those elements of the film that is completely open to audience interpretation. He talks about director Francesco Barilli, the Gaston Laroux story from which the title is borrowed, and the echoes and influences of previous movies. He also reveals that it was only shown on a single cinema for three days in the UK on an opposite colour double-bill with Claude Chabrol’s Scoundrel in White (1972). He makes some intriguing observations about the film itself, notes that it has a great score, stunning cinematography and no directorial missteps, and acutely observes that a key feature of giallo films is that they tend to throw suspicion on everybody to prevent you from guessing who the killer is.

Lovely Jon on Piovana: A Classical Approach (33:28)

Image-conscious but immensely knowledgeable DJ and soundtrack enthusiast Lovely Jon looks at the work of composer Nicola Piovani, with specific attention paid to his score for The Perfume of the Lady in Black. He outlines Piovani’s journey to becoming a film score composer, and the influence of Mozart on his work, and examines some examples of his soundtrack compositions. He also breaks down the themes of his score for The Perfume of the Lady in Black and deconstructs how music is employed in one key scene. In complete contrast to Eugenio Ercolani on the commentary track, he describes Roberto Benigni’s Life is Beautiful (which won Piovani his only Oscar) as a classic. I think it might be fun to get these two together.

Barilli’s Roma (5:51)

A leisurely look at four of the key exterior locations in which scenes from The Perfume of the Lady in Black were filmed, handily matched with shots from the film for us to appreciate how much or how little they have changed over the years.

Italian Theatrical Trailer (3:21)

A snappily edited trailer in which shots from the film selected specifically for their sinister or “what’s going on here?” feel are intercut with a red-tinted lithographic image of a wide open eye, with animated blinks used as transitions. There are plenty of spoilers here for those with sharp memories.

International Theatrical Trailer (3:21)

The exact same trailer as above, but with English titles, dialogue and narration, which differs from its Italian counterpart only in its linking of black magic to Africa, a continent that gets no mention in the Italian trailer.

Image Gallery

21 screens featuring production stills, lobby cards, newspaper ads, posters, a VHS video cover, and even a composite photo showing both sides of the soundtrack single.

Booklet

The lead essay in this typically well-produced accompanying booklet is by writer, director and producer Paul Duane. It’s an excellent piece that perceptively deconstructs the film’s subtle complexity and savvy technique, and I’m not just saying that because of how many times Duane’s observations coincide with my own, sometimes right down to his choice of words. One point I didn’t make that he explores persuasively is the key role played by reflections and mirrors in the film, which had me slapping my forehead in an “oh, of course!” gesture.

Mimsy Farmer’s shift from child actor to mature performer is discussed in a 1966 article from the Oroville Mercury Register, which does include a couple of quotes from Farmer, the nearest you’ll get to hearing from this interview-shy actress, who now works on films as a sculptor and whose credits in that role include Pan’s Labyrinth (2006) and Guardians of the Galaxy (2014).

Next is an interview with director Francesco Barilli, conducted by Roberto Curti for the December 2011 issue of Offscreen, and any fears you might have that this will just be the fourth run of stories about the making of The Perfume of the Lady in Black soon prove to be completely unfounded. This is a hugely detailed piece that covers Barilli’s entire film career up to the original publication date, including his early acting roles and work as an assistant director and screenwriter. Seriously, this runs for a whopping 44 pages of this 78-page booklet, three of which are devoted to the 34 footnotes that include references and further information on the text. It’s an excellent read, particularly for anyone unfamiliar with the specifics of Barilli’s career – even the discussion on Perfume is peppered with details that are unique to this interview.

Full credits for the film – which handily includes a clear explanation of the acronym CSC, which appears on two credits – and details of the transfer have also been included and the booklet is illustrated with stills and promotional material.

final thoughts

For me, The Perfume of the Lady in Black has proved one of those films that it took a couple of viewings to really click with and that now just seems to get better every time I watch it. Four viewings in now it’s easy to see why it’s held in such high regard by genre fans and it’s been handsomely served by this impeccable Indicator UHD release. A lovely transfer and a chest full of fine special features make this an absolute must-have. I can’t speak for the Blu-ray as I haven’t seen it, but this UHD is an absolute belter.