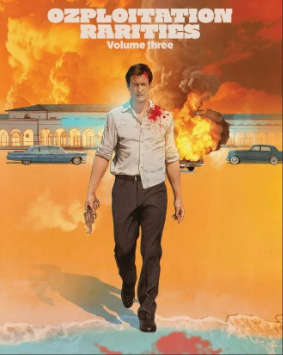

Ozploitation Rarities Volume 3

Umbrella Entertainment’s third OZPLOITATION RARITIES box set contains three films on the noirish side: SCOBIE MALONE, GOODBYE PARADISE and THE EMPTY BEACH, starring Jack Thompson, Ray Barrett and Bryan Brown respectively. Review by Gary Couzens.

Umbrella Entertainment have released three three-film box sets of what they call Ozploitation Rarities. This third set is labelled Ozploitation Goes Noir, with the three films centring on private eyes. That stretches a point in the case of Scobie Malone, as he’s a cop while Mike Stacey and Cliff Hardy work independently. Also, calling at least two of these films Ozploitation does them something of a disservice, as while they are certainly of a genre they aren’t the action movies, horror films or sex comedies often branded as such, some of-the-time female nudity notwithstanding. No doubt that’s a commercial consideration, as it bears out the idea that if you can call something Ozploitation it’s much more likely to have a restoration and a Blu-ray release than some classics of the 1970s and 1980s which now risk becoming invisible. But I’ll get off that soapbox now. Certainly Goodbye Paradise in particular is several cuts above much straight-to-video Ozploitation fare. We start with…

SCOBIE MALONE

Herewith more dots. Robinson was an American, born in 1903, who had begun his career writing intertitles for silent films. He directed nine shorts and one B-movie feature in 1931 and 1932 but clearly felt his talents lay elsewhere and switched to writing. He was Oscar-nominated for Captain Blood (1935), on which he has sole screenplay credit, but his writing CV is impressive indeed: it includes Dark Victory (1946), All This and Heaven Too (1940), King’s Rowand Now, Voyager (both 1942) and uncredited work on a little film also from 1942 called Casablanca. By the 1970s, he was retired and had relocated to Sydney due to marrying an Australian. However, Scobie Malone brought him out of retirement. Becoming involved as a producer, he rejected Cleary’s script and cowrote a new one with Woodlock.

One big change to the novel was to make Scobie a ladies’ man and so nudity abounds – all female, of course. Scobie lives in a singles-only apartment block where topless or nude bathing takes place and he frequently loses track of which air hostess he’s in bed with. (For Cleary’s reaction to this, see the interview with him among the disc’s extras, described below.) There’s an extra-cinematic frisson to this, as two of them are played by sisters Leona and Bunkie King (credited as respectively Lee King and Bunkie), with whom Thompson was having a polyamorous relationship in real life. (It began when Thompson was twenty-nine, Leona twenty and Bunkie fifteen and lasted some fifteen years until Bunkie left the ménage. Thompson is still married to Leona as I write this.) In addition to this, another of Scobie’s conquests is played by Victoria Anous, who was Thompson’s sister-in-law, married to his adoptive brother the film critic Peter Thompson.

All these shenanigans were an attempt to make Jack Thompson a star, on the back of his success in Petersen (1974) and Sunday Too Far Away (1975), and no doubt something of a sex symbol too. (He gets quite a bit of bedroom action in the former film, as well.) Yet somehow it didn’t stick, and the commercial and critical failure of Scobie Malone didn’t help. Other rather younger Australian actors became international stars, and indeed sex symbols, notably Mel Gibson, and Thompson pivoted to become an excellent character actor. (Another actor who did become an international star to some extent was Bryan Brown, who makes his debut here as a policeman early on, bottom of the cast list with his named misspelled “Brian Bronn”.) One issue is that the two-timeline structure, while faithful to the novel, sidelines the film’s leading man for large parts of the running time, and while Judy Morris is quite capable as Helga, it’s not her the film is really interested in. The film is rather flatly directed though it does make good use of the Opera House (which had opened in 1971) as a location.

Scobie Malone was critically derided and was dead on arrival at the box office. It didn’t trouble any awards bodies, though Thompson the same year won the Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor for his roles in Petersen and Sunday Too Far Away. As far as I have been able to tell, the film has not had any distribution, or even showings, in the UK. Plans for filming further Scobie novels came to naught, though in 1997 an adaptation of the 1992 novel Dark Summer for television was written but never made.

Herewith more dots. Robinson was an American, born in 1903, who had begun his career writing intertitles for silent films. He directed nine shorts and one B-movie feature in 1931 and 1932 but clearly felt his talents lay elsewhere and switched to writing. He was Oscar-nominated for Captain Blood (1935), on which he has sole screenplay credit, but his writing CV is impressive indeed: it includes Dark Victory (1946), All This and Heaven Too (1940), King’s Row and Now, Voyager (both 1942) and uncredited work on a little film also from 1942 called Casablanca. By the 1970s, he was retired and had relocated to Sydney due to marrying an Australian. However, Scobie Malone brought him out of retirement. Becoming involved as a producer, he rejected Cleary’s script and cowrote a new one with Woodlock.

One big change to the novel was to make Scobie a ladies’ man and so nudity abounds – all female, of course. Scobie lives in a singles-only apartment block where topless or nude bathing takes place and he frequently loses track of which air hostess he’s in bed with. (For Cleary’s reaction to this, see the interview with him among the disc’s extras, described below.) There’s an extra-cinematic frisson to this, as two of them are played by sisters Leona and Bunkie King (credited as respectively Lee King and Bunkie), with whom Thompson was having a polyamorous relationship in real life. (It began when Thompson was twenty-nine, Leona twenty and Bunkie fifteen and lasted some fifteen years until Bunkie left the ménage. Thompson is still married to Leona as I write this.) In addition to this, another of Scobie’s conquests is played by Victoria Anous, who was Thompson’s sister-in-law, married to his adoptive brother the film critic Peter Thompson.

All these shenanigans were an attempt to make Jack Thompson a star, on the back of his success in Petersen (1974) and Sunday Too Far Away (1975), and no doubt something of a sex symbol too. (He gets quite a bit of bedroom action in the former film, as well.) Yet somehow it didn’t stick, and the commercial and critical failure of Scobie Malone didn’t help. Other rather younger Australian actors became international stars, and indeed sex symbols, notably Mel Gibson, and Thompson pivoted to become an excellent character actor. (Another actor who did become an international star to some extent was Bryan Brown, who makes his debut here as a policeman early on, bottom of the cast list with his named misspelled “Brian Bronn”.) One issue is that the two-timeline structure, while faithful to the novel, sidelines the film’s leading man for large parts of the running time, and while Judy Morris is quite capable as Helga, it’s not her the film is really interested in. The film is rather flatly directed though it does make good use of the Opera House (which had opened in 1971) as a location.

Scobie Malone was critically derided and was dead on arrival at the box office. It didn’t trouble any awards bodies, though Thompson the same year won the Australian Film Institute Award for Best Actor for his roles in Petersen and Sunday Too Far Away. As far as I have been able to tell, the film has not had any distribution, or even showings, in the UK. Plans for filming further Scobie novels came to naught, though in 1997 an adaptation of the 1992 novel Dark Summer for television was written but never made.

GOODBYE PARADISE

“The winter sun was going down on Surfers Paradise. It was my ninety-eighth day on the wagon and didn’t feel any better than my ninety-seventh. I missed my hip flask of Johnny Walker, my ex-wife Jean and my pet dog Somare and my exorbitant salary as deputy commissioner of police. I wasn’t sure any more I was cut out to be a writer of controversial exposés of police corruption. At the moment I couldn’t lift a lid of a can of baked beans. I wanted to be twelve years old again, a spin bowler at Southport High. I wanted a lot of things. So did my landlady, including the rent.”

We know where we are in the opening scenes of Goodbye Paradise – the land of noir with a Raymond Chandleresque voiceover, even though we’re near the beach in Surfers Paradise. (Shot off season, though.) Mike Stacey (Ray Barrett) is an ex-cop turned private eye, quite a friend of the bottle, working on a massive book planning to blow the lid of police corruption. However, his publisher, who is boarding Mike’s dog, one of his few friends, doesn’t want it. Then Mike is summoned by Les McCredie (Don Pascoe), a politician involved in a campaign for the Gold Coast to secede from Queensland and form its own state. Les’s daughter Cathy (Janet Scrivener), who is Mike’s goddaughter, has disappeared and Les wants Mike to find her.

A rarity this might be, if an undeserved one, but calling this Ozploitation is something of a stretch. Yes, it is a genre film, of the branch of thriller or film noir centred on a private eye. Yet it contains elements of other genres, resolving into a conspiracy piece and a pitched battle. It contains song and dance numbers, diegetic ones in the bars and clubs of Surfers. Ray Barrett even gets to sing, in early scenes when Mike is in his cups. There are elements of satire on local politics which may pass non-Queenslanders and certainly non-Australians by. (Queensland was a very socially conservative state under premier Sir Joh Bjelke-Petersen, who was in office from 1968 to 1987 and whose administration was widely known for corruption.) It’s about half an hour longer than most exploitationers, and is classically paced to the extent that we spend a quarter of an hour (most of the first reel, for the celluloid-inclined) establishing place and character before Mike calls on Les and the inciting incident of the plot is incited. Ultimately, for all the genre trappings, occasional violence and some nudity, it’s a character piece and Ray Barrett rises to the occasion. This was, believe it or not, his first lead role in an Australian film (he certainly plays a lead role in Don’s Party, but that’s an ensemble piece) and won him the second of his three Australian Film Institute (AFI) Awards and the only one in the lead category. He’s the same age as his character (given as fifty-four and a half in one of the voiceovers) and he’s utterly convincing as a down-at-heel, somewhat disreputable man who has lived a life.

The other AFI win was for Best Original Screenplay, the work of Bob Ellis and Denny Lawrence, the latter also having a “based on an idea by” credit. Lawrence, who has more often worked as a director for television than as a writer, wrote the story as a treatment at film school and showed it to Bob Ellis, who immediately offered to write the screenplay with him. (According to the late Ellis, as told to David Stratton for the latter’s book on 1980s Australian cinema, The Avocado Plantation, Lawrence pitched it to him as “Raymond Chandler, Ray Barrett, Surfers Paradise, Carl Schultz.” To which Ellis’s reaction was that he hadn’t read Chandler, Barrett was too old, he liked Surfers and who was Carl Schultz?) Their writing process involved spending time in Surfers with Barrett (a native Queenslander, born in Brisbane). Despite the setting, funding came from another state, namely the New South Wales Film Commission, for a budget of $1.8 million. Some interiors were shot in Sydney, but the bulk of the film was made in Surfers. Many of the interiors were not studio sets but real locations dressed for the film.

As for Carl Schultz, funders were initially wary of him as his only previous feature film, Blue Fin (1978) had been unsuccessful and he had been removed from the production, with a few scenes shot by an uncredited Bruce Beresford. Born in Hungary, Schultz had emigrated to Australia, beginning his career in television, first as a cameraman and then as a director. Schultz keeps the film on the move and holds together its changes of tone, and is assisted by beautiful work by cinematographer John Seale, often shot in available light, or available light augmented by some subtle artificial light. Seale had worked his way up from being a camera operator in the 1970s and early 1980s for several leading DPs like Russell Boyd and Geoff Burton, and had indeed been Burton’s operator on Blue Fin. Seale went on to a distinguished career, winning an Oscar for The English Patient. He is now retired, coming back to shoot Mad Max: Fury Road and Three Thousand Years of Longing for George Miller. Seale and Schultz would reunite on the latter’s next film, Careful He Might Hear You (1984), which won them both AFI Awards and is one of the major Australian films of the 1980s and long overdue a Blu-ray release. Ellis and Lawrence reunited five years later, with both credited for the screenplay and original idea (the latter with Patric Juillet) for Warm Nights on a Slow Moving Train, which Ellis also directed.

Although it’s Barrett’s film, Ellis and Lawrence give plenty of opportunities for the rest of the cast. Second-billed Robyn Nevin doesn’t have a lot to do as Mike’s friend with benefits, but she makes the most of her limited time on the screen and is quite moving. Janet Scrivener, in a dual role (I’ll say no more to avoid spoilers) is remarkable, alternating hard-bitten cynicism beyond her years with a touching vulnerability. If she was a new name on me, that’s because this was her only film, with just five television episodes as her other IMDB credits.

Ultimately Goodbye Paradise goes off the rails a little towards the end with its out-of-place action finale, and at a shade over two hours is a little baggy. (That wasn’t unheard-of for Ellis. His original script for Newsfront (1978) would have made for a film of at least two and a quarter hours instead of the 111 minutes it finally ended up as. When it had to be cut down, for budgetary reasons as much as anything else, Ellis took his name off it, so in the final work has a “based on an original screenplay by” credit.) Shot in mid 1981, Goodbye Paradise didn’t find a distributor for about a year. According to debut producer Jane Scott, she was told it was too unconventional and difficult to handle. Before the film was released, it was entered into the AFI Awards. As mentioned above, it won for Best Actor and Best Original Screenplay and was nominated for Best Film and Best Director, beaten by Lonely Hearts and Mad Max 2 respectively. John Seale was awarded Cinematographer of the Year by the Australian Cinematographers’ Society.

Goodbye Paradise didn’t appear in cinemas until July 1983 and was not successful. Some of that may have been down to cultural cringe: Australians have often not been big supporters of their own films in their cinemas. That’s a pity as it’s several cuts above most Ozploitation fare and is by some way the best of the nine films that Umbrella have released in their three (so far) Ozploitation Rarities box sets.

THE EMPTY BEACH

Bondi, Sydney. Cliff Hardy (Bryan Brown) is a private eye, approached by Marion Singer (Belinda Giblin) to look for her husband, who was supposedly drowned two years earlier. Hardy is led to Bruce Henneberry (Nick Tate), a journalist who has supposedly incriminating tapes in his possession. However, he is murdered. Henneberry’s girlfriend Anne Winter (Anna Maria Monticelli) helps him as the trail leads Hardy into some murky waters…

If Jon Cleary could boast of twenty Scobie Malone novels, Peter Corris might have said Hold My VB, or words to that effect. Corris was a prolific writer – again, details on how he was are in the documentary – but his Hardy novels number thirty-five, plus six collections of Hardy short fiction, from The Dying Trade in 1980 to Win, Lose or Draw in 2017, the year before Corris died. In addition to that, he had two other series (Richard Browning, eight novels, and Luke Dunlop, three) plus standalone historical novels, non-fiction and an academic book from before he was a full-time writer. Needless to say, interest in screen adaptations of his work began early. The second Hardy novel, White Meat (1983), was to be filmed, starring Bryan Brown as Hardy, with Stephen Wallace directing, who had worked with Brown on the prison drama Stir (1980). However, that fell through. It was Brown who had taken out the option on the novels, but the one which did reach the screen was novel number four, The Empty Beach, published in 1983.

Corris was hired to write the screenplay, but it wasn’t used. The credited screenwriter was Keith Dewhurst, who was British though living in Sydney at the time. Dewhurst’s track record was in his home country and on television, with single plays and episodes of drama series of the time, such as Z Cars and Softly Softly. His previous Australian work were episodes of the miniseries Luke’s Kingdom, broadcast in 1976. In fact, The Empty Beach was his first cinema-feature credit, of only two – the other was his last credit, The Land Girls in 1998. He died in 2025. Producer Bob Weis and director Chris Thomson worked on the final draft.

The production was not an easy one. The costume department provided Anna Maria Monticelli with flowing gowns to disguise the fact that she was pregnant. There were clashes between director and star, and director and cinematographer – John Seale, who had returned to Australia after shooting Witness for Peter Weir in the USA. Corris was one of a few people who saw an early cut of the film, which he liked with reservations. That was about five minutes longer than the final version and had no music. David Stratton, who also saw that early version, found it superior and so did Corris. The music score is by Martin Armiger, who had been the guitarist in Melbourne band The Sports and had moved on into musical direction and film and television scoring, and Red Symons, the British-born lead guitarist of Skyhooks. There was also a title song, by Marc Hunter, which was released as a single. The loss of five minutes cuts the film to the bone, which makes parts of it not easy to follow, at least on a first viewing, which is all what most people had. There are good things about the film, with Seale’s camerawork making the most of the Bondi locations, including the famous beach.

The leading cast is mostly good, with Ray Barrett on the other side of the law this time. A long way down the cast you can find Rebecca Smart in one scene at the age of eight. This was actually her third screen role (after being Greta Scacchi’s daughter in The Coca Cola Kid in the same year, 1985, and before that the Kennedy Miller-made miniseries The Cowra Breakout. She would go on to play opposite Brown in the 1987 miniseries version of The Shiralee and in 1989 would give one of the great Australian child performances in the title role of Celia. (Her younger brother Aaron is in the same scene, pressed into service when the original child refused the play the scene, sitting on the toilet with his shorts down.) Brown is an ideal cynical and tough Cliff Hardy, and you can see how he could have played the role a few more times had the film been more successful. However, it wasn’t. It should have been called The Empty Cinema, Corris quipped. It went straight to video in the UK. This was New Zealand-born Thomson’s debut cinema feature. His next one was the 1989 The Delinquents, made to capitalise on Kyle Minogue’s stardom. The rest of his career was on television, and he died in 2015.

sound and vision

Ozploitation Rarities Volume 3 is a three-disc set released by Umbrella Entertainment, the Blu-rays encoded for all regions. The box and all three films carry the M rating, which is advisory, particularly for those under fifteen. Scobie Malone and Goodbye Paradise have never been submitted to the BBFC, but The Empty Beach was passed uncut at 18 for its British VHS release in 1987. It would certainly have a 15 now.

All three films were shot in 35mm colour. The Blu-ray transfers of Scobie Malone and Goodbye Paradise are in the intended ratios of 1.85:1. The Empty Beach is in Scope, with the transfer correctly in 2.35:1. It was shot not with anamorphic lenses but in Super 35, making it one of the earliest Australian films to do so, a year before Dead-End Drive-In and Dogs in Space. (To tell the difference, in an anamorphic film, out-of-focus background lights will be vertical ovals, while in Super 35, shot with spherical lenses, they will remain circular. Also, a full-frame copy of a Super 35 film will show additional picture area at the top and/or bottom of the frame, for example in the clips from The Empty Beach in the music video among this disc’s extras.) It’s not indicated from which materials the restorations have been made from, but all three films look very good, and the differences are due to the originals: Scobie Malone being much more brightly-lit and Goodbye Paradise generally more shadowy. Grain is natural and filmlike and not as evident as you might think in The Empty Beach, which being a Super 35 shoot, might be expected to be grainier.

Scobie Malone was released with a mono soundtrack, which is rendered here as LPCM 2.0. Goodbye Paradise was an early Australian Dolby Stereo film (the first was Mad Max 2 the previous year) and that’s the basis of the sound mix here, rendered as DTS-HD MA 2.0. It plays in surround, which announces itself straight away with the music score and the sound of waves breaking on the beach. No doubt the battle scene at the end, with gunfire and helicopters, would have given the speakers a workout in the very few Dolby-equipped cinemas the film played in. The Empty Beach also had a Dolby soundtrack, also rendered as DTS-HD MA 2.0, and the sound design clearly has some fun with directional sounds during the shoot-out scene.

Subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available for the features only. As so often with Umbrella releases, these could have been better. Various attempts to describe music scores are redundant, as is something like “(screams)” on a close-up of someone screaming. There are also a number of errors, particularly for Goodbye Paradise. There’s a difference between “blue bottles” and “bluebottles” (15 minutes), and we get “very good and bad” instead of “very good in bed” (109 minutes) and I have no idea what an “old fenton” (83 minutes) is. “Should of” for “should have” or “should’ve” (at 76 minutes) is simply ungrammatical.

special features

SCOBIE MALONE:

Commentary by Stephen Vagg and Justin King

This is a commentary by two third parties, neither involved with the film itself. Stephen Vagg is a critic and screenwriter and a prolific contributor to Umbrella releases. Justin King was a researcher on Not Quite Hollywood, which is how he got to see Scobie Malone, which he rates quite highly – more highly than anyone else it would seem. Vagg provides most of the production details, having interviewed Jon Cleary (see below) and also read the source novel and others in the series. The film’s two timelines have their origin in Helga’s Web. Some of King’s claims are a bit of a stretch: I don’t see much connection with this film and the work of Brian De Palma and Dario Argento, for one, especially as it predates their best-known works. He’s right in that Sydney is very much a character in the film, though I’m not sure we should “overlook the foibles of the era”.

Murder at the Opera House: An Interview with Sue Milliken (11:00)

Sue Milliken, now a film producer of long standing, talks about her beginnings in the industry. She started at ABC television as a typist, then moved into continuity, beginning with episodes of Skippy. In that capacity she worked on Scobie Malone, and also The Carmakers (see below). Despite that, she has few memories of director Terry Ohlsson, but has more about Casey Robinson, Jack Thompson, Noel Ferrier and others of the cast.

Not Quite Hollywood interviews (11:26)

These interviews were recorded for Mark Hartley’s 2008 documentary Not Quite Hollywood, which has been the source of many a disc extra over the years. Here we have three of the cast talking about Scobie Malone, with a chapter stop per interview. None of them are particularly long, as no doubt they didn’t have a lot to say about the film. Jack Thompson doesn’t think the film particularly hangs together, and he thought he was better as a sex symbol in the TV show Spyforce. Judy Morris says that the film looks quite sexist to today’s eyes, but it was an Australian film made with an intended international feel. She speaks fondly of Casey Robinson, though notes he was prone to taking naps on set. Victoria Anoux says that she had no contact with the writer or director when she was on set, but was able to perform a love scene with Thompson, having done that already on Spyforce.

Interview with Jon Cleary (19:01)

This interview (audio only) is part of an oral history Stephen Vagg conducted with Jon Cleary in 2004 as part of his research for his biography of Rod Taylor. (Cleary died in 2010, aged ninety-two.) Needless to say, given the Rod Taylor connection, The High Commissioner takes up a big part of the discussion, but Cleary does talk about the writing of the novel Helga’s Web and the film Scobie Malone. This interview is the source of Cleary’s much-quoted reaction to the film: with the fourth shot of Scobie’s lips on a woman’s nipple, he said, “That’s not my Scobie,” and walked out. As of this interview, he hadn’t seen the rest of the film and you suspect he never did. There is also talk of the later attempt to revive Scobie for the screen in 1997, with a Peter Yeldham script and David Wenham playing the part.

The Carmakers (48:08)

This 1973 TV production was one of two other directing credits for Terry Ohlsson. (The third was a short, The Green Machine, from 1977. He was more active as a producer into the 1990s and died in 2018.) It’s clearly intended for an hour-long television slot, with a fade to black roughly halfway through so a commercial break could be inserted. If it wasn’t shot in 16mm it certainly looks like it, and the print this has been transferred from has certainly seen better days. Along with Ohlsson, it shares with Scobie Malone the services of Keith Lambert as cinematographer, Graham Woodlock as screenwriter, Sue Milliken on continuity and Walter Sullivan in the cast. It’s a curious piece, a combination of documentary on and advertorial for Leyland Australia and their soon-to-be-released P76 car, and a perfunctory industrial espionage plot with publicist Ray Barrett and journalist Katy Wild being trailed by corporate spy Noel Ferrier. In an arch touch, Barrett and Ferrier are playing characters with the same names as themselves. At this point, Barrett was working extensively in the UK and wouldn’t return to Australia, noticeably craggier than he is here, until 1976 for Don’s Party. Yet here he is three years before that – was this is a quick job while he was in his home country on a short visit?

Jack Thompson trailer reel (47:19)

Another Umbrella trademark is the thematic trailer reel. As usual, the trailers for these films, starring or featuring Jack Thompson, are arranged in chronological order. Each has its own chapter stop, but there are no identifying captions at the start of each one, so knowing what order they are in makes it easier to find a particular trailer. So, as a public service, here is a list of the films being trailed: Wake in Fright (1971, a US TV spot under the title Outback), Libido (1973 – certainly not safe for work), Petersen (1974 – also not safe for work), Sunday Too Far Away (1975), Caddie (1976), Mad Dog Morgan (1976), The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), ‘Breaker’ Morant (1980), The Earthling (1980), The Club (1980), The Man from Snowy River (1982), Australia (2008), Blinder (2013), Mystery Road (2013), Don’t Tell (2017), Swinging Safari (2018), Never Too Late (2020), High Ground (2020) and, bang up to date with his most recent film as I write this, Runt (2024). You’ll note a big gap there between 1982 and 2008, which misses out several notable films, and also the trailer for Scobie Malone itself isn’t included.

Trailer for The High Commissioner (1:37)

However, the trailer for Scobie’s previous outing, when he was in London and looked like Rod Taylor, is included. It’s a decent trailer for a watchable if not entirely successful film. This is presented with an initial caption, which notes its alternate title of Nobody Runs Forever.

In the case for Scobie Malone is a double-sided A3 poster, that for the film on one side and that for The Empty Beach on the other.

GOODBYE PARADISE:

Commentary with Jane Scott, John Seale, Denny Lawrence and Stephen Vagg

No one who was involved in the film’s making, other than Sue Milliken, appears in new extras for Scobie Malone. However, on this admittedly more recent film, on the commentary track we have the film’s producer, cinematographer and co-writer, with Stephen Vagg, the only Queenslander among them, stepping in to moderate. That’s always a good idea with a film that’s now over forty years old and you have some fairly elderly participants whose memories may need jogging. Vagg puts his cards on the table at the start by calling Goodbye Paradise one of the greatest Australian films ever made. Lawrence had known Carl Schultz from the six-part TV serial Run from the Morning (1978). He goes into some detail about the writing process, giving Ellis credit for much of the character material and dialogue, commenting that for someone who hadn’t read Chandler he did a good job of pastiching him. He could model himself on anyone, says Lawrence. He also blames Schultz for a rather on-the-nose shot of a snake in the Eden-like commune which forms part of the plot. Seale contributes a lot of technical detail on the film’s production, with some of the darker scenes pushed two stops in development to enable shooting in low light, and Scott describes some of the aspects of what was not a particularly high-budget shoot. They are all clearly proud of their work here.

Tanned and Dangerous: An Interview with Grant Dodwell (12:46)

Grant Dodwell appears in the film in two scenes, as “Seaworld Boy”, much of which is extracted in this item, including the only example of male nudity in the whole two hours. Goodbye Paradise was his second feature film, after Cathy’s Child in 1979. However, he had been acting on television for eight years and around the time of making Goodbye Paradise was starting a six-year and 343-episode stint on A Country Practice. Dodwell emphasises how small an industry Australia’s was, especially compared to the American equivalent where he worked for a while. He came to Jane Scott’s attention because he knew her then husband. He had worked with Bob Ellis on stage for the latter’s play The Legend of King O’Malley (a still is provided) which also featured Robyn Nevin in the cast. He found Carl Schultz a calming presence on set, and Ray Barrett thanked him for his participation after his scenes had been shot. Looking back, Dodwell had forgotten he draws a gun in the film. Nowadays, Dodwell is involved with Australian Theatre Live, which provides recordings of stage productions to theatres and streaming platforms.

Paradise in Peril: An Interview with Carl Schultz (33:58)

Made in 2019, this interview was the only extra on Umbrella’s then DVD of Goodbye Paradise. The director’s name is misspelled as “Shultz” on the disc menu and packaging. Schultz was born in Budapest on 19 September 1939, eighteen days after Germany’s invasion of Poland, so because of the War, he didn’t go to school until he was seven. After the Hungarian Uprising of 1956 he and his brother left Hungary for Austria and eventually England, first London and then Manchester, despite then speaking no English. Two years later, Carl Schultz left for Australia, where a cousin lived. He spent ten years working for ABC Television as a cameraman but soon developed an interest in directing, beginning in 1972 with the series Over There. His experience on Blue Fin is clearly a sore point still: he was removed before the film could be edited and, as he puts it, shaped. Goodbye Paradise was a happier experience, though he says he feels it is a little indulgent and if he could he would re-edit it to make it tighter, and he appreciates Bob Ellis and Jane Scott’s insistence that he direct it. Finally, he shows us the key chain, a clapperboard with his name inscribed on it, which Scott gave him as a present.

Stills Gallery (1:45)

A self-navigating gallery, featuring a press card, stills (mostly black and white, some colour), some pages from the press kit and poster designs.

TV Spot (0:32)

A brief item that emphasises the film’s feel of several genres in one, so we get bits of the battle sequence near the end, several shot of Ray Barrett and a voiceover which claims this is “the wildest comedy-thriller of the year”. All this adds to the feeling that this wasn’t an easy sell and is in danger of setting up expectations which the film itself wouldn’t meet. As this spot is from Australian television, it quotes the M rating and tells us the film starts on Saturday at Hoyts Civic.

The case for Goodbye Paradise also contains a double-sided A3 poster, with two different designs for this film.

THE EMPTY BEACH:

Commentary with Bryan Brown, John Edwards, Larry Eastwood and Stephen Vagg

This commentary is newly recorded, as moderator Stephen Vagg says at the outset, not very far away from the setting of the film itself. As well as star Bryan Brown, present are producer John Edwards and production designer Larry Eastwood. Brown gets proceedings off to a not-good start by saying he doesn’t remember much of the film. Edwards, however, remembers more. He talks about negotiations with Stephen Wallace about his Cliff Hardy film that never happened. Writer Keith Dewhurst, who lived in Palm Beach at the time, was “very Pommy” and also happened to be the son-in-law of Brown’s agent. Bob Ellis saw the film before release and hated it, offering to write a new voiceover. Edwards also says that The Empty Beach was one of the first Australian films to be released in China.

Private Eye in Bondi: An Interview with Bryan Brown (8:30)

A new interview with the star, conducted by Stephen Vagg. Brown says he doesn’t take on a film if it isn’t there in the script. The Empty Beach gave him the opportunity to play the lead in a contemporary film, after a lot of period/historical films like ‘Breaker’ Morant. In fact, he said, contemporary-set crime films were not usual in Australia at the time, though he later played the villain in one – Two Hands, for which (as he doesn’t say) he won the AFI Award for Best Supporting Actor. He saw The Empty Beach as an Australian film drawing more on popular literature rather than the classics filmed in the 1970s and 1980s. The Bondi setting was a plus, given that family trips there in childhood were a treat from where he lived in the western suburbs, and he was always envious of the children he saw who didn’t need to go home at the end of the day because they lived there. Brown does wonder if he could play a rather older Cliff Hardy again.

Winter by the Sea: An Interview with Anna Maria Monticelli (13:34)

Also interviewed by an offscreen Stephen Vagg, Anna Maria Monticelli talks about her career. Although she is Australian, her film debut was in New Zealand, in Smash Palace (1981), of which a clip is seen. She was billed as Anna Jemison then, her first married name, but 1985 was the year she changed her stage name back to her birth name. She had been working in the USA when she was called by producer Bob Weis for The Empty Beach. She found Hollywood “a cruel place”. However, she talks fondly of the late Chris Thomson, who is represented here, as with the Brown interview, by behind-the-scenes footage from his next cinema feature, the Kylie Minogue vehicle The Delinquents (1989).

Dead Quick: Peter Corris – Writer (55:43)

In this television documentary, first broadcast in 1994, the author of the source novel of The Empty Beach sets out his stall in voiceover from the outset: “I don’t take risks as a writer. I don’t agonise or pull my hair out. I write for ordinary people, not the literary elite. I love to write and people seem to enjoy the books. I don’t have any original ideas about human behaviour and motivation. I don’t have the ability to break new ground or to produce really powerful original fiction; I can’t do it and I don’t want to. I’m perfectly happy doing what I’m doing. I do it the easy way. I’m a square peg in a square hole.” In between dramatisations of scenes from his novels, and Corris bumping into his own characters from time to time (Robert Menzies plays Cliff Hardy), Corris talks about his life and his career. Sydney has formed a large part of his work, since he moved to the suburb of Glebe as, he says, a “refugee from academic life in Victoria”. He talks about boxing and his love/hate relationship to the sport, as his first non-academic book was about it, called Lords of the Ring, before he wrote fiction.

This isn’t an uncritical profile, presumably with his knowledge and approval. Two commentators talk about his work. Stuart Coupe, editor of the crime fiction magazine Mean Streets, is positive with some reservations. On the other hand, Rosemary Sorensen, editor of Australian Book Review, takes Corris to task, basically for being what he unashamedly is, a writer of genre fiction, often to a formula and, speaking as a woman, often very male-gazey. Corris acknowledges all of this, but makes it plain that his work rate is necessary to make a living as a writer in Australia. He writes five to six pages (1200-1500 words) a day, every day, which means a shorter novel in six weeks. He writes four or five novels a year, sometimes putting a longer historical novel in there, and earns $6-7000 per novel. Having said all that, and acknowledging that he will never win any awards (he did go on to win two Ned Kelly Awards for Crime Writing, including one for lifetime achievement in 1999) he is proud of the fact that he has a place on the Sydney Writers Walk, some sixty metal plaques inset into the footpath on Sydney’s Circular Quay.

Corris is frank about other issues, describing how in many ways the sexual content of his novels makes up for what he describes as his own inadequacies, not always comfortable with the male role as the initiator. He gets an “Oh, Dad!” from one of his daughters as we see them and his wife (Jean Bedford, whom the documentary doesn’t mention was and is also a writer). In fact, he and Bedford were married then split up, after which she married again and when that ended she and Corris remarried. Corris also talks about living with Type 1 diabetes, and credits ophthalmologist Fred Hollows with saving his life. He was proud to work with Hollows on his autobiography. Corris is clear that his health may not last with his condition, but he tries to maintain a healthy lifestyle and he might have twenty years in him. That proved to be correct, as he passed away in 2018 at the age of seventy-six. As this documentary was made before The Empty Beach, what we don’t have are any comments on what remains the only screen adaptation of one of his novels.

Marc Hunter “The Empty Beach” music video (3:56)

The title song of the film, a solo effort by Hunter, who was the vocalist of the New Zealand rock band Dragon. It was released as a single, and this is the video which features Hunter and backing vocalist Wendy Matthews amongst some clips from the film. The director of this promo was the late Kimble Rendall, then a rock guitarist and singer (XL Capris and Hoodoo Gurus) who had become a director. His later feature films included Cut (2000) and Bait (2012).

Bryan Brown Aussie Trailer Reel (38:00)

Another thematic trailer reel, for the film’s star’s Australian films, including early ones where his role was small and he doesn’t actually appear in the trailer. Each one has its own chapter so you can skip to a particular one if you wish, though they don’t have the film’s title as a caption beforehand.

So we have, in chronological order, the trailers for The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith (1978), Newsfront (1978), Money Movers (1978), The Odd Angry Shot (1979), ‘Breaker’ Morant (1980), Stir (1980), Winter of Our Dreams(1981), Far East (1982), The Empty Beach, Blood Oath (1990), Sweet Talker (1991), Two Hands (1999), Dirty Deeds (2002), Australia (2008), Red Dog: True Blue (2016), Sweet Country (2017) and Palm Beach (2019). That last, directed by his wife Rachel Ward, allows me to add a piece of Brown trivia. He is one of what can’t be many actors to have acted, in this case in lead roles, in two otherwise unrelated films with the same title. The other one was in 1980, directed by Albie Thoms. (For another Australian nearly-example, Chris Haywood in the same year, 1985, was in both Burke & Wills and Wills & Burke – close, but no cigar.)

Storyboards (3:30)

Chris Thomson’s storyboards for the film’s shootout scene, in a self-navigating gallery.

Theatrical trailer (1:39)

A serviceable attempt to sell the film as the action thriller it isn’t really. However, as this trailer is in the Bryan Brown trailer reel, its inclusion on the disc as a separate item is redundant.

Booklet

Umbrella’s booklet with this release runs to forty-eight unnumbered pages, plus covers. It begins, as usual with previous box sets in this series, with an overview of the three films by Paul Harris. That’s almost the only original content in the booklet, with the rest of it made up of articles from contemporary newspapers and magazines, sometimes reproduced in a font so small it’s hard on the eyes. So we have Mike Harris on a location report on Scobie Malone for The Australian. Some of the illustrations might not be safe for work. Then, in colour, Movie News on Jack Thompson, “our new Errol Flynn”. On to Goodbye Paradise, with Alexander McGregor’s location report for the Sydney Morning Herald and a lengthy interview with Ray Barrett for Cinema Papers and pages from the film’s press kit.

Next up is “Empty Beaches: Australia’s Missing Big Screen Private Investigators” by Andrew Nette, a new piece by a fan of the film, one once hard to track down other than via pricey used VHS copies. Why have there been so few Australian private-eye films, he wonders, given that the genre flourished in pulp magazines there for some three decades. These begin with Carter Brown (the pseudonym of Alan Yates), who was English-born and set some three hundred novels in American cities. Other writers from the time included K.T. McCall (a team of two women, Audrey Armitage and Muriel Watson) and Charles Shaw. The genre declined in the 1970s, but Peter Corris was part of a revival in the next decade. Nette talks about some other quite diverse Australian films featuring private eyes, which includes Terry Bourke’s diabolical sex comedy Plugg (1975, described by one critic, Brian McFarlane, as the worst Australian film ever made, with some stiff competition), via Goodbye Paradise, to Samantha Lang’s interesting The Monkey’s Mask (2000), from the verse novel by Dorothy Porter, starring Susie Porter as a lesbian PI investigating a murder and becoming involved with chief suspect Kelly McGillis.

This is followed by another piece from the Sydney Morning Herald, this time by Bronwyn Watson, and a piece from Cinema Papers concentrating on Bryan Brown.

final thoughts

The score third time round, is one of the best films released on Blu-ray as Ozploitation (if you accept it as such), with two flawed but not uninteresting others. None of them were especially commercially successful, hence the word Rarities, and Umbrella have provided a comprehensive set of extras. Unless you saw them on their brief cinema releases, these films on disc look the best they ever have.

Ozploitation Rarities Volume 3

Scobie Malone

Australia 1975 | 98 mins

directed by: Terry Ohlsson

written by: Casey Robinson, Graham Woodlock, from the novel Helga’s Web by Jon Cleary

cast: Jack Thompson, Judy Morris, Shane Porteous, Jacqueline Kott, James Condon

Goodbye Paradise

Australia 1982 | 123 mins

directed by: Carl Schultz

written by: Bob Ellis, Denny Lawrence

cast: Ray Barrett, Robyn Nevin, Guy Doleman, Lex Marinos, Paul Chubb

The Empty Beach

Australia 1985 | 90 mins

directed by: Chris Thomson

written by: Keith Dewhurst from the novel by Peter Corris

cast: Bryan Brown, Anna Maria Monticelli, Belinda Giblin, Ray Barrett, John Wood

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

related reviews: