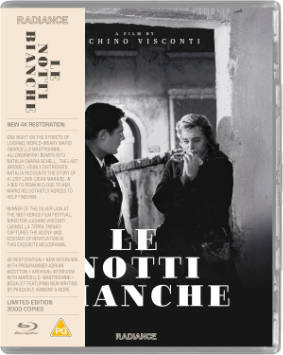

Le notti bianche

Luchino Visconti’s LE NOTTI BIANCHE [WHITE NIGHTS], from 1957, comes to Blu-ray from Radiance. Gary Couzens waits by a bridge.

Livorno, Italy. Mario (Marcello Mastroianni), a clerk, arrives in town where he stays in a boarding house. One night, he sees a young woman, Natalia (Maria Schell), standing on a bridge over a canal, crying. After some reluctance, and the unwanted attention of local bikers, Mario strikes up a conversation with her, and they agree to meet the next night at the same place. She explains that she is waiting for her lover (Jean Marais), who rented a room in her grandmother’s house. They fell in love, but he left abruptly, promising to return in a year. It is now more than a year later…

Le notti bianche (often known in English as White Nights, no relation to the 1985 film directed by Taylor Hackford, but as Radiance are using the original Italian title, I’ll do the same) is an odd one out in Visconti’s filmography. It followed Senso (1954), which is now usually regarded as one of his greatest films, but it certainly wasn’t at the time. He was attacked for betraying the tenets of neo-realism, though you could argue that the film is neo-realist if you allow a historical setting, a wealthy part of society and its being in colour. It had also been an expensive film which had not made its money back and Visconti was gaining a reputation for being profligate. So, while his position as a theatre and opera director was secure, as a film director Visconti was seeking to prove that he could make a film on time and on budget, and Le notti bianche was the result. Cowritten by Visconti and regular collaborator Suso Cecchi D’Amico, the film is based on Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1848 novella Belye noche (some 20,000 words in the English translation I sourced), though updated from mid-nineteenth century Russia to contemporary Italy. Another adaptation of the same novella was Robert Bresson’s Four Nights of a Dreamer (Quatre nuits d’un rêveur, 1971), in that case updated to present-day Paris.

Location shooting in Livorno was prohibitive, so the entire film was shot in the studios at Cinecittà, and in black and white. It’s necessary to remember that however much they might be auteurs, making films even for arthouses was a commercial endeavour and directors sometimes had to compromise for their films to be made. The Leopard (Il gattopardo) was in colour and the large-format widescreen process Technirama (and shown in 70mm in some venues), but Visconti made two of his next three feature films in black and white: Rocco and His Brothers (Rocco e suoi fratelli, 1960), although he had wanted to shoot that in colour, and Sandra (Vaghe stelle dell’orsa aka Of a Thousand Delights, 1965). By that point, black and white was becoming commercially obsolete in the west, and the remainder of Visconti’s films were in colour.

In 1957, black and white often denoted naturalism and realism, especially as black and white stock was then more sensitive to light than colour and better able to shoot in available light. Colour was still thought to be better suited for musicals and historical spectaculars, and you could certainly say that Senso was along the latter lines. Yet black and white could be used to create a fairytale atmosphere – as a good and relevant example, Jean Cocteau’s Beauty and the Beast (La belle et la bête, 1946). It’s not hard to envisage that Visconti had that film in the back of his mind, especially as that film’s star Jean Marais is third-billed here. Le notti bianche combines the two modes. Although the film is entirely studio-bound, the sets (production design by Mario Chiari) are not just large but intensely realistic. We’re in a modern world of cafes and bars, characters riding motorbikes and Mario arriving at the start in a bus which stops outside an Esso garage. So yes, realistic rather than stylised, with the exception of an obvious cyclorama for a sky. Yet, due to the production, costume design (Piero Tosi) and the masterly cinematography of Giuseppe Rotunno, it’s a creation of cinematic artifice. Rotunno had worked for Visconti as the camera operator on Senso, and had shot some scenes after cinematographer Robert Krasker (who had taken over from the co-credited G.R. Aldo after his death) had had to leave for another film due to overruns. Rotunno shot three more feature films for Visconti, plus the latter’s segments of the portmanteau films Boccaccio ’70 (1962) and The Witches (Le streghe, 1967). Part of the artifice are the weather conditions which play a part of the story: variously, rain, fog and snow.

Maria Schell has top billing. Her career was at something like its peak, having won a prize at Cannes for The Last Bridge(Die letzte Brücke, 1954), and, the year before Le notti bianche, Best Actress at Venice for René Clément’s Gervaise, for which she was also BAFTA-nominated. She was also working in the UK and, later in the decade, in Hollywood. She’s very affecting here, speaking her lines in Italian, a language she didn’t speak so she had learned them phonetically in two weeks. Marcello Mastroianni matches her, in his first film collaboration (of two) with Visconti, though they had worked together on stage for the previous ten years.

Given the number of adaptations of the story – as well as this and Bresson’s version, Wikipedia lists five other films, from Russia (twice), Iran, India and the USA, plus its “inspiration” of James Gray’s 2008 Two Lovers – it’s a story that clearly works, and it does here, to poignant effect. Visconti began in the neo-realist movement, which was waning at this point, and he certainly displayed operatic tendencies which came to the fore later in his career. Le notti bianche shows both streams in Visconti’s work delicately counterposed, as it does the strains of realism and fairytale.

Le notti bianche premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 1957, where it won the Silver Lion. It opened in London on 9 May 1958, its main London venue being the Curzon in Mayfair. Cahiers du cinéma called it the third best film of 1958, after Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal in second place and Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil first.

sound and vision

Le notti bianche is released on Blu-ray by Radiance, a disc encoded for Region B only. The film was cut for an A certificate in British cinemas in 1958 and is a PG on this disc.

The film was shot in black and white 35mm and this Blu-ray transfer is in the intended ratio of 1.66:1, based on a 4K restoration. This goes to show how much a lost art black and white cinematography is, recent examples notwithstanding. Though there are blacks and some whites, there is a wide greyscale, and grain looks fine.

The soundtrack was mono in cinemas and remains that way on this disc, rendered as LPCM 1.0, and no issues to report. As far as I’m aware,

was shot without sound, like just about every other Italian film of the time. Lipsynch is good, as Visconti was clearly taking pains to make it so, unlike his compatriot Federico Fellini, for example. If he had shot this, Maria Schell might have delivered her lines in her native German (and Jean Marais in French), but she does so in Italian, which she had learned phonetically. In some of Visconti’s other films it’s clear that actors weren’t speaking their lines on set in the same language we hear on the soundtrack, but that’s not the case here. English subtitles are optionally available, on by default, on the feature and all the non-anglophone extras, so that’s everything except Adrian Wootton’s appreciation and the audiobook.

special features

Interview with Adrian Wootton (23:16)

New to this release, Adrian Wootton gives a thorough appreciation of the film. He begins with Visconti’s situation at the time, resulting in the film being entirely studio-bound, becoming the mixture of realism and artifice it is, with the bridge at the centre of the story linking Natalia’s fantasy world to Mario’s real one. Wootton identifies several of the film references – Beauty and the Beast most obviously, but asserts that the film is not a “movie-movie” but a “fairytale-fairytale”. He discusses the careers of Schell and Mastroianni. She was top-billed and was the star then, however much cineastes today would think of him as the bigger name. Wootton also talks about Giuseppe Rotunno and Nino Rota. This film kicked off what became a trilogy of collaborations for the latter with Visconti, followed by Rocco and His Brothers and The Leopard. (Rota was uncredited for his musical adaptation in Senso. He also scored Visconti’s segment of the portmanteau film Boccaccio ’70, as well as Fellini’s segment of the same film.)

Audiobook reading (108:09)

Dostoevsky’s novella in English translation, as an audiobook. It plays as an alternative audio track to the main feature, but is differently chaptered: five of them, one for each section of the original story. The first-person-male-viewpoint story is read by four readers, alternating female and male, in order Jennifer Anne Shivel, Bill Boerst (chapters two and three), Cam Ha and Ulf Bjorklund, the last two of whom don’t give their names at the ends of their sections. As the audiobook runs five and a half minutes longer than the feature itself, it continues over a black screen after the “Fine” and the final restoration credits have gone past.

Letters from Rome: Luchino Visconti (32:41)

Filmed for French television in 1963 with Visconti speaking that language, he is interviewed by André S. Labarthe, at first in a drawing room and later on a Roman roadside with a flock of sheep behind them, kept from straying into the road by a low stone wall. At this time, Visconti was working on The Leopard and Labarthe makes comparisons with Senso, also a historical literary adaptation in colour. Visconti points out that those films depict a changing society, while La terra trema, for example, depicts one which is largely unchanged. He makes two exceptions to this general rule: Bellissima (1951), which he calls a portrait (of Anna Magnani) rather than a film, and Le notti bianche. He says that the use of colour in Senso (and presumably the then-not-yet-made The Leopard) was not a casual thing, but intended to be a dramatic element in the film. He wanted to make Rocco and His Brothers in colour, but the budget would not allow it. Visconti embraces the term melodrama, suggesting that it’s not an alien sensibility to an Italian, and talks about his work with Jean Renoir, whom he thinks is someone of an incalculable influence on him, despite the short time they collaborated.

Archival interview with Marcello Mastroianni (3:37)

This is from 1977, the year after Visconti’s death, and clearly part of a longer piece. Mastroianni talks about his work with Visconti, beginning with ten years with him on stage. The twelve or so productions they did together included A Streetcar Named Desire, with Mastroianni playing Stanley Kowalski. He was one of the production partners behind Le notti bianche, which was his first big-screen work for Visconti. Mastroianni says that Visconti always had a clear idea of the day’s scene and direction when he arrived on set, and had a free run as to what plays he wanted to put on, no doubt due to not being short of a few lire.

Le notti bianche: An Appreciation (16:52)

From 2003, this is a wide-ranging piece discussing the film, introduced by Laura Delli Colli and interviewees including then-surviving principal crew members Giuseppe Rotunno, costume designer Piero Tosi and screenwriter Suso Cecchi D’Amico. They talk about their contributions to the film, with Tosi mentioning how he and Rotunno worked together to create the look of this black and white film – clothes were picked in particular colours so that they came out as darker or lighter shades of grey. Critic Lino Micchechè gives some background to the political and cultural temperature at the time. The 1956 revolution in Hungary, put down by the Soviets, had caused a reevaluation and something of a crisis among those on the left, of which Visconti was one, despite his aristocratic background. This had a knock-on effect in the cinema, as the thought and theory behind neo-realism had been influenced by the left and most of its adherents leaned that way.

Trailer (5:37)

A lengthy trailer which suggests that this film might not have been an easy sell in Italy in 1957, given how much of the plot and scenes wherein it shows. At this time the film wasn’t brand new, so the trailer is able to include a caption detailing its Venice Festival win.

Stills gallery

Fifty black and white stills for this black and white film, each separately chaptered, so you can advance or go back via the buttons on your remote.

Booklet

This limited-edition release comes with a booklet featuring new writing by Pasquale Iannone and by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith from the archive, but this was not available for review.

final thoughts

Le notti bianche is an oddity for Visconti, tending to be overlooked compared to some of his other films, but is certainly worthy of attention in its own right. This release, benefiting from a recent digital restoration, allows the film to be seen for its own merits, not least for the beauty of its black and white cinematography.