The House of Mirth

Terence Davies’s THE HOUSE OF MIRTH, from Edith Wharton’s novel, starring Gillian Anderson, arrives on Blu-ray from the BFI as part of their retrospective in the month of what would have been Davies’s eightieth birthday. Gary Couzens heads off to New York City in the Gilded Age.

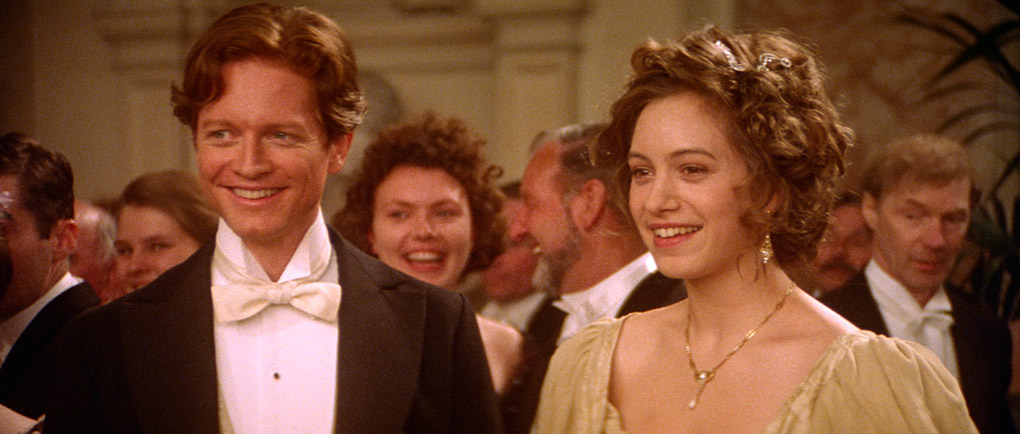

New York City, 1905. Lily Bart (Gillian Anderson) lives with her aunt Julia (Eleanor Bron), living off a small allowance. She is attracted to Lawrence Selden (Eric Stoltz) but his circumstances make this not a good match, especially as Lily is living beyond her means in order to keep up with the society she inhabits. Meanwhile, Gus Trenor (Dan Aykroyd) offers to help her earn money through investment, but there’s a catch…

On its release in 2000, The House of Mirth seemed something of a departure for Terence Davies, though it is one of his best films. It contains a career highlight from Gillian Anderson as tragic heroine Lily Bart in an adaptation of Edith Wharton’s novel. Davies had made his reputation with films derived from his childhood and adolescence in Liverpool. This began with the three films which made up his autobiographical trilogy, shot in black and white 16mm, comprising one mid-length film and two shorter ones: Children (1976), Madonna and Child (1980) and Death and Transfiguration (1983). Similarly to the other major semi-autobiographical trilogy in British cinema, that of Bill Douglas, in that case both beginning and ending in the 1970s and funded by the BFI, Davies’s transmutes memories, sometimes painful, sometimes ecstatic, in its portrayal of one man’s life from childhood to old age and death. In some ways, you can read the Trilogy (shown and distributed as a unit since its completion) as an alternative self-history, the path Davies’s life might have taken if he hadn’t had the talent or opportunity to pursue an artistic calling and was consigned to a shipping office for the whole of his working life.

The Trilogy forms the first panel of a larger trilogy. The second instalment was Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), which is a diptych of mid-length films shot two years apart, this time in 35mm colour. In it, Davies explored his family history in 1940s and 1950s Liverpool, with his stand-in’s coming of age, concentrating on his brutal father in the first half, but weaving into the mix the popular culture of the time, from pub singalongs to the films at the local cinemas which so enraptured the young Davies. This greater trilogy was completed in 1992 with The Long Day Closes, which used many of the same themes and techniques at feature length. So after six films derived from his own life was The Neon Bible (1995), from the novel by John Kennedy Toole. It’s again a coming-of-age tale of a boy, though set in Georgia in the 1940s. It was as if Davies expanded his themes and techniques by finding a sympathetic story in existing literature.

The House of Mirth seemed different, although it’s also a literary adaptation. It’s set further back, in the early years of the twentieth century in moneyed New York, and this time it has a female lead. It’s a close examination of a milieu that Wharton (1862-1937) clearly knew well, as she had been born into it. The House of Mirth, published in 1905, was her second novel and her first success, a considerable one. Davies’s film follows the novel closely, but eschews the voiceover narration by Joanne Woodward that Martin Scorsese used in his 1993 film The Age of Innocence, from the 1920 novel which made her the first woman to win a Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. Davies conveys Wharton’s voice by other means, not least the dialogue which largely drives the film. Although some of it is Davies’s pastiche of Wharton rather than words lifted from the novel, the effect is seamless. While Davies does move his camera, the style is more self-effacing than Scorsese’s, though some of that may have been due to budget restrictions necessitating filming in Glasgow, standing in for New York with the aid of some discreet CGI.

The story is one of a trap closing around its heroine, from a position as a “jeune fille à marier” (as she puts it)having reached a point in life – her late twenties – where the search for a husband and financial security is becoming urgent. Davies’s era of popular culture was the 1940s and 1950s (in Of Time and the City (2008), he makes it very clear what he thought of his fellow Liverpudlians The Beatles) and he had never watched The X Files before casting Gillian Anderson. He was taken aback to find out how famous she was; to him, she looked like someone who could have walked out of a John Singer Sargent portrait painting. There was a similar story to Rachel Weisz’s casting in The Deep Blue Sea (2011).

The House of Mirth premiered at the New York Film Festival in September 2000 and was released the following month in the UK, December in the US. It did not receive Oscar attention, but in Britain it was BAFTA-nominated as Best British Film and for Monica Howe’s costume design, losing to Billy Elliot and Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon respectively. However, for nearly a decade, Davies was unable to make another film. He appeared on BBC Radio with an original play, A Walk to the Paradise Garden (2001) and a two-part adaptation of Virginia Woolf’s The Waves (2007). But as far as the cinema went, projects fell through (including an adaptation of Lewis Grassic Gibbon’s Scottish classic Sunset Song, which he was finally able to make in 2015) and funding was not forthcoming. This was a dark and personally debilitating period for Davies, who had difficulties in making ends meet, often, as he put it, swapping one debt for another. He continued to write screenplays, originals as well as adaptations. The drought was broken with the documentary Of Time and the City, a valentine to his native city, in 2008. This was followed by two literary adaptations – The Deep Blue Sea, from the Terence Rattigan play, and Sunset Song – and two literary biopics, both of poets, A Quiet Passion (2016) about Emily Dickinson, and Benediction (2021), on Siegfried Sassoon. As I mentioned in my review of the previous BFI release, Priest, directed by Antonia Bird, British cinema of the 1980s and 1990s is littered with names who were unable to sustain a cinema career beyond one or two or so features and often ended up working in television. At least Bird was able to make four features for the big screen, though she spend the last decade and a half of her career and life back on the small one. And at least Davies did get to make the eight features (plus the Trilogy and the documentary) he did make, but there’s a sense that once again, a national cinema did not do well by one of its finest filmmakers.

sound and vision

The House of Mirth is released on Blu-ray by the BFI, on a disc encoded for Region B only. The film had a PG certificate on its original cinema and DVD release, but for a cinema reissue in conjunction with a BFI retrospective in the month of what would have been Terence Davies’s eightieth birthday, it was raised to 12A and is a 12 on this disc.

The film was Davies’s second in Scope (after The Neon Bible), shot in 35mm with anamorphic lenses. This Blu-ray transfer, derived from a 2K scan of the original internegative, is in the intended ratio of 2.35:1. Colours are strong, and in keeping with previous viewings (cinema and HD streaming), and grain looks fine. For technical reasons I have been unable to source screengrabs from the disc, so this review is illustrated with BFI publicity images.

The House of Mirth played in cinemas with a Dolby Digital soundtrack, and that’s the source of the sound mixes on this disc, available in both DTS-HD MA 5.1 and LPCM 2.0 iterations, the latter playing in surround. There is barely any difference between the two in this very dialogue-driven film, the surrounds being used mainly for the mostly-classical music score and some directional sounds such as rainfall. The disc also includes an audio-descriptive track in Dolby Digital 2.0. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available for the main feature, the featurette, on-location footage and cast and crew interviews. I spotted one slight error: in the location footage, “Listen to him” should be “Listen to Remi [Adefarasin, the cinematographer]”. Sixty-seven minutes into the main feature, the subtitles translate Ned’s poetry reading of Verlaine to Bertha Dorset in the original French, which is left untranslated if you watch the film without them.

special features

Commentary by Terence Davies

This commentary was recorded in 2001, for that year’s DVD release of The House of Mirth. While it’s good to have something (interviews apart) from the film’s director, especially as he’s now deceased, this isn’t one of the best. (Davies has been good commentating on other people’s films, for example as one of the participants in the Kind Hearts and Coronets track. That film was an all-time favourite of his and not his own work, so that no doubt helped. See also his TV documentary on another favourite of his, Bergman’s Cries and Whispers.) Much of this commentary is scene-specific, with Davies interpreting the film for us, and there are increasingly long gaps as the film goes on. That said, there is some useful information here, such as his pointing out the various Glaswegian locations (some of them CGI-enhanced to turn them into New York), and the various ways his adaptation deviates from the novel. He’s especially proud of lines of dialogue which were his rather than Wharton’s, even if some of them weren’t spotted by reviewers at the time.

Commentary by Marc David Jacobs

Many all-bells-and-whistles limited edition releases include multiple commentaries, in some cases I can think of as many as five. Whether the film in question merits that many is another question. However, this release of The House of Mirth is a model of having more than one commentary which properly complement each other. To whit, this newly-recorded track by Marc David Jacobs.

Jacobs accounts for Davies’s commentary at the outset, pointing out that Davies – unlike his more-or-less-contemporaries Bill Douglas (eleven years older) and Derek Jarman (three years older), all of whom emerged in the 1970s, all of whom benefited from BFI funding at one time or another – lived into the age, perhaps the golden age, of disc commentaries, on DVD and later Blu-ray. That was despite the fact that Davies didn’t especially like to talk about his own works. In contrast to Davies’s track, Jacob’s is almost entirely non-scene-specific, drawing heavily on Davies’s archive regarding this film. (He acknowledges the archivists’ assistance at the end.) There are few pauses as Jacobs doesn’t let up for the full two and a quarter hours, finally stopping as the end credits appear on screen. We have a lot about Davies’s background, including the fact that he first became aware of Edith Wharton’s novel when he heard a serialisation of it on the radio. (With a little help from BBC Genome, that might have been either Radio 4’s five-parter from 1981 or Anna Massey reading it as a Book at Bedtime in 1972.) The film followed The Neon Bible, which Davies perceived as a failure. (That film has only been distributed in the UK in the cinema and VHS, with occasional television showings since. No doubt the BFI would not be alone in putting it out on Blu-ray if it weren’t AWOL, though I’m not aware of the reason why it is.)

Jacobs refers to Davies’s screenplay which is annotated with the dates and even times when particular scenes were written. An exception to this are the scenes written during the month of Davies’s mother’s death. Very close to her, Davies contemplated taking his own life when she died. Physical description is kept to a minimum. The names mentioned as being considered for the cast are fascinating. For Lily alone, at one time or another Cate Blanchett, Embeth Davidtz, Madeleine Stowe and Miranda Otto were in the frame, and when Gillian Anderson was cast, the other contender then was Sharon Stone. Todd Field, then mired in the lengthy shoot for Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, and before he became the director of In the Bedroom and Tár, was at one point due to play Laurence Selden, a role which Davies found hard to cast. None other than Jean Anderson and Phyllis Calvert were to play Aunt Julia before Eleanor Bron did. Jacobs comments on the fact that Davies only made period and historical films, and all of them are about people unable to escape the bounds of society. Interestingly, the writers Davies adapted, including Virginia Woolf, or in the case of A Quiet Passion and Benediction made biopics of, include two suicides, one tragically early death, one hermit and two closeted gay men. There is also, intriguingly, talk of the rival version of The House of Mirth which was in the works in the late 1990s, to be directed by John Schlesinger and written (not directed) by Ken Russell and, later, Frederic Raphael, which was eventually never made. There are also mentions of the now-lost 1918 film of the novel (did Wharton ever see it?) and Scorsese’s film of The Age of Innocence. This is an excellent commentary with plenty to get your teeth into.

Featurette (7:24)

One of three extras presumably derived from the film’s electronic press kit, all available with optional English subtitles. This is a mixture of behind-the-scenes footage, clips from the film itself and to-camera interviews with cast and crew. In order of appearance, these are Davis, Dan Aykroyd, Eric Stoltz, Gillian Anderson, Olivia Stewart (producer) and Laura Linney.

On-Location footage (10:46)

The cast and crew at work outside in Glasgow, a series of short sequences punctuated with somewhat abrupt cuts to black. There are no captions or voiceover, but the context of each is clear enough. I suspect this is a one-watch item, though.

Cast and crew interviews (26:33)

Interviews to camera, parts of which also appear in the featurette above. These follow the usual EPK format of the question appearing on screen as text, followed by the person’s answer, often not much more than a soundbite. In order of appearance: Davies (in two locations, with a change of clothes from one to the other), Olivia Stewart, Gillian Anderson, Dan Aykroyd, Eric Stoltz, Laura Linney and, not in the shorter version, Anthony LaPaglia under an umbrella with rainfall on the soundtrack.

Deleted scenes with optional commentary (17:07)

To be accurate, these are extended scenes rather than deleted ones, preserving the original versions of three of them before Davies had to shorten them to keep the film to its final length of 140 minutes. There is a Play All option and an optional commentary by Davies. Sometimes less is more, he says, but sometimes less is less. The scenes in their full version were felt too dense for their position in the film, though the shortened versions do elide some plot points and remove some character introductions. The individual scenes run 5:50, 3:00 and 8:09.

Still Lives: The House of Mirth (17:57)

Newly recorded for this release, this featurette has Caroline Millar, associate professor in English Literature and creative and professional writing at Canterbury Christ Church University. She is, most pertinently, a specialist on Edith Wharton and a fan of the films of Terence Davies. The novel is a product of, and the film is set, in what (citing Mark Twain) was called the Gilded Age. Note the “gilded”, not “golden”: the glisten is all on the surface. Millar, who is reading from visible notes, draws on clips from the film, and also from Distant Voices, Still Lives – particularly when highlighting Davies’s repeated image of umbrellas. She highlights Davies’s use of artifice – though some of that was budgetary, given that the production had to shoot in Glasgow rather than New York – in particular the scene where Lily appears as a tableau (Summer by Watteau, a scene changed from the one in the novel). Millar sees Wharton’s novel, and Davies’s film, as an illustration of the dilemma of whether inspiring art or being an artist. Wharton certainly inclined to the latter, being quoted as wanting to escape into the “secret garden” of writing.

Image gallery (4:03)

A self-navigating gallery, including drawings, set plans, some handwritten script pages, stills and some on-set Polaroids, much of it from the Terence Davies archive at Edge Hill University.

Trailers (3:33)

Two of them, with a Play All option: a recreated version of the original trailer (1:48) and one for the twenty-fifth-anniversary reissue (1:45), which inevitably is able to include critical praise.

NFTS Back Stories: Terence Davies (80:41)

In 2021, the National Film and Television School celebrated its fiftieth anniversary by interviewing famous alumni –via Zoom, as those were pandemic times. Here it’s the turn of Davies, interviewed by Sandra Hebron. On this disc, this plays as an audio track over the main feature, replaced by film audio after it ends. The video version can be viewed at the NFTS website.

At the time, Davies was in post-production on Benediction. Hebron takes him through his life and career. He came from a working-class background where university was out of the question: if he was bright enough, he’d work in an office, otherwise he might take an apprenticeship. However, cinema was an early love, beginning when he saw Singin’ in the Rain at seven. He watched just about everything, in the evenings after work in a shipping office. He talks about more recently seeing a new print of Seven Brides for Seven Brothers and found himself sitting near Jane Powell and was so overcome that he couldn’t approach her.

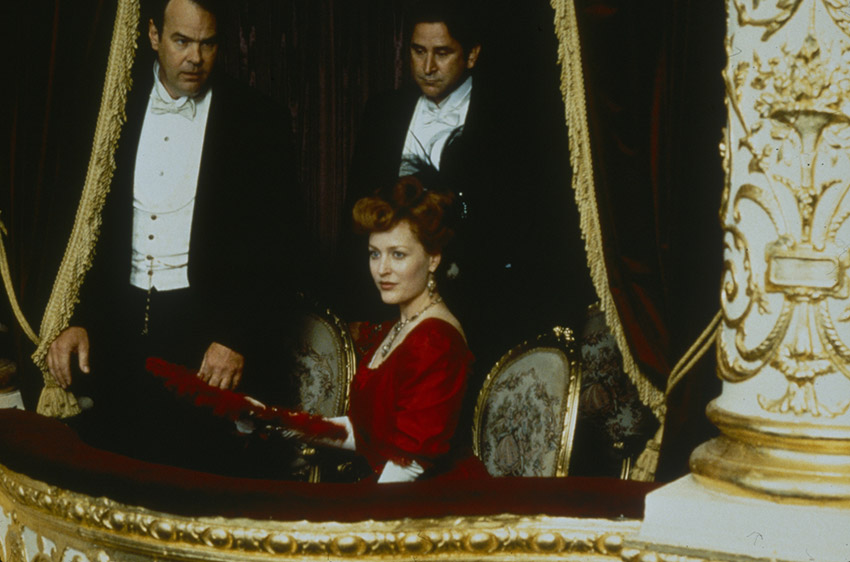

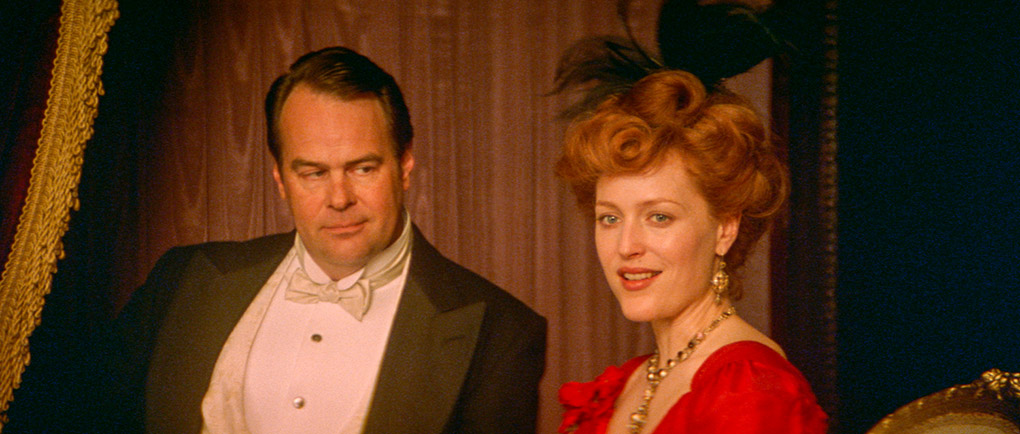

He credits Mamoun Hassan of the BFI for rescuing him from the shipping office, a fate that his counterpoint in the Trilogy never escapes. He was given £8000 to make Children (1976), but other than his cinematographer William Diver (with whom he worked again) he had constant opposition from the crew, destroying his confidence in the film which he only regained when working with the editor Sarah Ellis. Madonna and Child (1980) was made as his graduation film from NFTS and caused a stir for some of its content, given that it’s the most overtly gay-themed work in Davies’s filmography. He talks about his process of writing, which results in screenplays which are more or less the finished film, as he doesn’t improvise on set. Some of the darker scenes are not pleasant to watch or film: for example, the scene where Ewan effectively rapes Chris in marriage in Sunset Song was filmed just the once, regardless of whether it worked or not. He is meticulous about the delivery of dialogue, saying that if he can deliver lines without a pause then an actor can, and if there’s no comma or similar punctuation mark, there’s no pause. Davies talks about visual references for his films. Production designer Andy Harris pointed him towards the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi for Sunset Song, while for The House of Mirth it was James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent. As for his reasons for making all his films set in period or history, he says that he doesn’t understand the modern world and is indeed repelled by aspects of it. Davies distrusts nostalgia, finding it too easily sentimental, but much of his work is an attempt to recapture a time of his greatest happiness, roughly between the ages of seven and eleven.

Davies is on darker ground when he talks about the long period after The House of Mirth when he couldn’t make a film as “no one was interested”. The British film industry wanted to make films that played in America rather than those as essentially British as his, even the three set in the USA. Hebron suggests that Davies “lacks a layer”, resulting in a greater sensitivity that’s as much a burden as a gift. Towards the end, Hebron reads questions from the online audience. At the time of the interview, Davies was working on an adaptation of The Post Office Girl, by Stefan Zweig, source writer of Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948), which Davies calls the greatest film about unrequited love ever produced. Sadly, this was never made. Davies died on 7 October 2023, at the age of seventy-seven.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release, runs to thirty-two pages plus covers. After a spoiler warning, it begins with “And One Must Go On Living” by Lillian Crawford, which begins with the ornate opening credits, similar to those on The Long Day Closes. Crawford then discusses Davies’s adaptation, over two screenplay drafts, highlighting parts of a copy of the novel as he did so. The result is quite faithful to Wharton, with a few changes (Lily’s cousin Grace Stepney, played by Jodhi May, also incorporates Selden’s cousin Gerty Farish, a separate character in the novel). Crawford gives us a close analysis of the film, highlighting repeated Davies motifs (characters watching from the seats of a cinema or theatre, for example).

This is followed by “Beauty’s Still Fade” by Philip Horne, reprinted from the October 2000 issue of Sight & Sound. This begins by pointing out that The Neon Bible, Davies’s first non-autobiographically-inspired film, was of a piece with his earlier work. Although more of a conventional narrative than those earlier films, it still employed similar stylistic devices to them. In social milieu (and in the lack of show tunes and pre-rock-’n’-roll pop songs), The House of Mirth seemed quite a departure, not least in its look, due to a change of production designer and cinematographer (previously Christopher Hobbs and Mick Coulter on both The Long Day Closes and The Neon Bible, now Don Taylor and Remi Adeferasin respectively). There is also the reduction of music and a greater emphasis on sound effects. Horne looks at Gillian Anderson’s performance and Davies’s filming of her: often a shot of her back is as eloquent as a close-up. So is Davies’s eye for small gestures. Horne does compare Davies’s film with Scorsese’s, wondering why the two best versions of Edith Wharton, who was not a Catholic, were made by two noticeably Catholic directors. This piece concludes with an interview of Davies.

“It Was a Day for Impulse and Truancy: Edith Wharton” by Daniel Graham is, as the title indicates, a look at the source novelist, born in New York on the site of a current Starbucks. Despite writing not being considered a suitable occupation for a girl, she persisted and became a chronicler of what became called The Gilded Age. Henry James recognised her talent early on and became a friend and something of a mentor. Her literary success had an adverse effect on her marriage. Although never really happy (“melancholy was her oxygen”, Graham says) that success continued. The House of Mirthearned her the then-enormous sum of $2.5 million. This is followed by a reprint of Kevin Jackson’s review of the film from the November 2000 Sight & Sound, and credits for and notes on the extras.

final thoughts

Although it seemed something of a departure when it was first released, The House of Mirth sits well in Terence Davies’s filmography. Part of that is due to the fact that literary adaptations were more or less what he could get made in a career which was too intermittent for all its distinction. That said, it’s a film showcasing a fine performance by Gillian Anderson and is well served on this BFI Blu-ray.