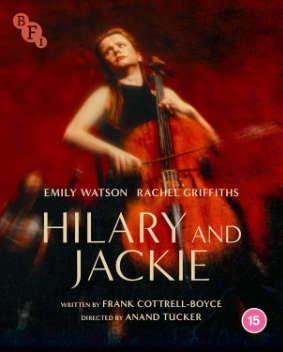

Hilary and Jackie

HILARY AND JACKIE, the story of celebrated cellist Jacqueline du Pré, featuring Oscar-nominated performances from Emily Watson and Rachel Griffiths, is released on Blu-ray by the BFI. Review by Gary Couzens.

The story of Jacqueline du Pré (1945-1987, played by Emily Watson) would make a compelling film if it simply centred on her. Her considerable talent was noticed at a young age and she won a prestigious award at the age of eleven. She was one of the greatest cellists of her time, but this all came to an end in her mid-twenties with the onset of multiple sclerosis, leading to her early death. However, Hilary and Jackie takes a broader approach.

Note the order of names, and the diminutive used of the person without whom this story would not exist. Hilary and Jackie is based on the memoir A Genius in the Family, by Jacqueline’s older sister Hilary (born 1942, played by Rachel Griffiths) and their younger brother Piers (born 1948, Rupert Penry-Jones). The sisters were born to a musical family. Their mother Iris (played by Celia Imrie) was a gifted pianist and composer, given to writing short compositions enclosed in cards to her children. World War II and then marriage to Derek (Charles Dance) and a family put paid to her musical career, and there’s a hint in the film that she encouraged her daughters to have the fulfilment of their talents that she had not been able to have. At first, Hilary was considered the talented one of the two, her instrument being the flute, with Jackie tagging along – in one scene given a drum to bang during a performance while Hilary solos and breaking the drum skin in petulance. This incident has an echo later in the film.

By making this a tale of two sisters, a story of the family rather than simply that of the genius in it, Frank Cottrell Boyce’s adaptation retells a common story where more than one person (siblings as here, or parent and child) excels in particular field and rivalry develops. There’s the hard fact that while many are talented, much fewer can be said to have actual genius, and that can be difficult for the non-genius to come to terms with this, particularly if the genius’s behaviour seems unworthy of their stature. Without the family relationship, that’s the story of Peter Shaffer’s play and later film Amadeus, with Hilary and Jackie this story’s Salieri and Mozart. Add to that the entitlement a first-born can feel, undermined when she is usurped by her younger sibling. As Jacqueline’s career progresses, Hilary steps back, marries conductor Christopher “Kiffer” Finzi (David Morrissey) and establishes a life in the countryside, rearing chickens and bringing up children, four of them. Meanwhile, Jacqueline marries Argentinian pianist Daniel Barenboim (James Frain), converting to Judaism at the same time, and builds her career, playing all over the world, until her illness strikes. Hilary delivers the key line of the film as she tells her sister, “If you think being an ordinary person is any easier than being an extraordinary one, you’re wrong.” The sense of a cutting down to size, in the face of Jacqueline’s often selfish behaviour, is unmistakeable.

The fact that Jacqueline and Hilary’s final meeting was on a notably dark and stormy night would seem absurdly melodramatic if it wasn’t true. That was the Great Storm of the night of 15-16 October 1987, the most violent weather event to have hit the south of England in 284 years, since the 1703 Great Storm witnessed by Daniel Defoe. Jacqueline du Pré died on the 19th, aged forty-two.

We begin with effectively a twenty-three-minute prologue, with Hilary and Jackie played as children by Keeley Flanders and Auriol Evans respectively. Griffiths and Watson take over their roles eighteen minutes in. The screenplay divides the film into two named sections: at first centring on Hilary for forty-three minutes, then on Jackie for the rest of the running time. Inevitably, in a two-hour feature film, Cottrell Boyce streamlines a lot. The story concentrates on the female members of the family, with father and brother on the sidelines. Piers du Pré’s talent for electronics is briefly sketched in. He went on to found a leading telecommunications company, du Pré plc, which is still in existence.1 The screenplay is carefully constructed, with Cottrell Boyce placing small details which play off against later scenes, from Jackie’s habit of blowing raspberries, to the scene with the drum mentioned above which recurs to the end of the film to strong effect. It’s hard to avoid the final scenes being very moving, and they duly are. Importantly, the film emphasises that while musical genius may be god-given it still requires constant practice, often to the exclusion of other parts of the life of a child or teenager. There’s a short scene which shows this, as Jacqueline, Daniel and a violinist practise a Beethoven trio before making a segue into The Kinks’s “You Really Got Me”.

Anand Tucker directed and does a fine job, but this is a film which belongs to its writer and cast at least as much. Rachel Griffiths and Emily Watson were both Oscar-nominated, in the Best Supporting Actress and Best Actress categories respectively. (Both lost to Shakespeare in Love, Judi Dench and Gwyneth Paltrow respectively.) While Watson gets her share of actorly fireworks, with portraying serious and eventually terminal illness and disability often the stuff of awards, actually much of the heavy lifting is done by a beautifully understated performance from Griffiths. Watson had come to prominence with her deservedly acclaimed performance in Lars von Trier’s Breaking the Waves two years earlier (for which she was also Oscar-nominated) and Griffiths had come to the fore in her native Australian for Muriel’s Wedding. They were born in the later 1960s respectively and it no doubt says much about the film industry’s view of women in middle age and older that they tend to be seen in character roles nowadays rather than leads worthy of their abilities. Hilary and Jackie is the centrepiece of a few years in the late 1990s when Griffiths was largely based in the UK. Since then, she had a leading role on television in Six Feet Under between 2001 and 2005. She has also since become a director, helming the engaging 2019 Australian sports biopic Ride Like a Girl.

Hilary and Jackie was released in the UK on 22 January 1999 and immediately attracted controversy. This was led by friends and colleagues of Jacqueline, who saw the original memoir and the film based on it as something of a settling of scores by one sister over the other, who was of course no longer around to put her case. To them, the film was something of a hatchet job on Jacqueline, particularly the scenes where she urged Hilary to let her sleep with Kiffer, that as sisters they should share everything. Daniel Barenboim was quoted as wondering why the filmmakers hadn’t waited until he was dead – he’s still here, about to turn eighty-three as I write this. The film certainly hints that he was seeing other women while Jacqueline was still alive. Hilary’s daughter Clare Finzi called the film a “gross misinterpretation”. Hilary herself wrote in The Guardian, “At first I could not understand why people didn’t believe my story because I had set out to tell the whole truth. When you tell someone the truth about your family, you don’t expect them to turn around and say that it’s bunkum. But I knew that Jackie would have respected what I had done. If I had gone for half-measures, she would have torn it up. She would have wanted the complete story to be told.” Of course, that’s impossible to confirm and Hilary is inevitably speaking for her late sister. While the film was moderately commercially successful and had awards recognition (it’s undeniably very well made and acted), there’s a sense that maybe the controversy has caused it to fade into the background in the last quarter-century.

sound and vision

Hilary and Jackie is released by the BFI on a Blu-ray encoded for Region B only. The film had a 15 certificate in cinemas and retains that on disc. Among the extras, Instruments of the Orchestra and Our Magazine No. 2 were both U on their original cinema releases, as was The Hornung Symphony Orchestra, while the other two Hornungs don’t appear to have been classified before. The first two are documentaries containing nothing that would exceed a U, let alone a PG, so are exempted for classification on this release.

It should be noted that this isn’t the version of Hilary and Jackie which played in British cinemas, and which I saw in early 1999. Just before the final sequence, around 106 minutes in, we should see Michael Fish’s infamous BBC weather forecast of 15 October 1987 reassuring a concerned viewer and us that a hurricane is not on the way. There is a still an acknowledgement of this clip, licensed from BBC Worldwide, in the film’s end credits. This presumably accounts for the difference in running time of this Blu-ray (120:18 at 24 frames per second) and the cinema release (122:09, also at 24 fps, as per the British Board of Film Classification). The film was classified twice for homeviewing in 1999, eight months apart, and there was a drop of a minute and a half between those two as well – 117:04 and 114:16, both with PAL speed-up. I have not been able to find an explanation for this.

The film was shot in Super 35 and was released to cinemas in 2.35:1. Some homevideo and television versions would have been in a narrower ratio – most likely 1.78:1 or 16:9, that of widescreen television sets – which instead of cropping the picture at the sides would have kept the full width and increased the height, revealing picture area not intended to be seen in the cinema. (For an example, see the trailer amongst this film’s extras.) The transfer is derived from a HD master supplied by Channel Four and there’s not much to say about it. The colours seem true, with solid blacks, and the grain seems natural and filmlike.

Hilary and Jackie was released with a Dolby Digital soundtrack, which is rendered as LPCM 2.0 on this disc, which plays in surround. As well as the music on the soundtrack, often using the surrounds, the film has a notable sound design, particularly in the more expressionist later stages as Jackie’s illness progresses. English subtitles for the hard of hearing are available for the main feature, and I didn’t spot any errors in them. Usefully, they indicate the classical pieces being played at particular points in the film. The spoken language in Avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton is French, and English subtitles are optional.

For technical reasons, I have been unable to take screengrabs from this disc, so this review is illustrated by BFI publicity stills.

special features

It’s notable that this relatively recent film, with most of its principal cast and crew still alive, features almost none of them on this Blu-ray release. The only contribution is a short note by producer Andy Paterson in the booklet. Instead, the extras, other than the commentary, feature short films that are tangential to the main feature’s subject matter, which the BFI are very fond of doing on their releases.

Commentary by Neil Brand

A feature film about a musician has a commentary from another musician, in this case a pianist. Neil Brand is a longtime silent-film accompanist as well as a composer, author and broadcaster. His commentary isn’t dominated by the film’s music aspects, as you might expect, and it does tend to be scene-specific. He is upfront in his admiration for the film, which he reckons contains two of the greatest performances of the decade. Like me, he sees it more of a writer’s and actors’ films rather than a director’s. Although Anand Tucker is given his due, he pays more attention to Frank Cottrell Boyce’s script and its construction, mentioning that it was written at the same time as Hilary and Piers’s memoir, which in a slip of the tongue he calls a novel at one point. Brand does address the controversies which followed the film’s release. He also points up the contributions of score composer Barrington Pheloung (without too much musicology) and costume designer Sandy Powell, whose contribution is one you might overlook otherwise. (She wasn’t Oscar-nominated for this but did win that year for Shakespeare in Love.)

Theatrical trailer (2:24)

A trailer which seems to be derived from a VHS source – it’s certainly lower-resolution than you might expect and there is tracking noise near the bottom of the screen. It’s presented in 1.78:1, so has additional picture height compared to the main feature.

Avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton (51:46)

A feature film about a real-life cellist includes an extra about another real-life cellist. Chantal Akerman fans should take note, as she directed this for French television in 2003. It wasn’t included in either of the two box sets the BFI released earlier this year and which I reviewed for this site. It is a profile of Sonia Wieder-Atherton. Akerman auteurists might find slim pickings here, though, as this documentary is almost entirely self-effacing on her part, other than a brief voiceover narration at the start. She removes herself as much as possible so as to put her partner in life centre stage. Akerman films Wieder-Atherton straight on as she talks to camera about her life and her musical inspirations, beginning on the piano and switching to strings, at first the guitar and finally the cello, because she can “make sounds last a long time”. Then most of the running time is taken up with performances of eight pieces, either solo or with one or more other musicians (pianist Imogen Copper, cellists Sarah Iancu and Matthieu Lejeune).

Instruments of the Orchestra (20:12)

Made for the Central Office of Information in 1946, this short piece is explicitly intended to introduce younger people to orchestral music. Malcolm Sargent talks to camera and introduces the various parts of the orchestra in simple terms, in the three ways of producing sounds from instruments – blowing, scraping or banging. Or in other words, woodwind and brass, strings and percussion. The London Symphony Orchestra take up the task, with an arrangement of Benjamin Britten’s Variations on a Theme by Purcell designed to showcase individual sections of the ensemble in turn as Sargent takes us through them. This piece later became The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, which remains one of Britten’s best-known works. Its educational value was obvious and the film was given wider exposure than most COI shorts by being given a cinema release. It was directed by Muir Matheson, most active as a score composer or musical director on feature films.

Our Magazine No. 2 (9:58)

Those who have bought and watched the BFI’s many Children’s Film Foundation releases will be familiar with Our Magazine. As well as the main feature (usually a three-reeler just under an hour) and shorter films you would have documentary material like this, in the hope that you might learn something as well as being hopefully entertained. This was the second Our Magazine, from 1952, and it packs four different items into its ten minutes. The first is the reason why it’s on this release: a look at the London Fields Primary School Percussion Band, of which none of the boys and girls on screen are over the age of seven. Once that’s done, we learn how to make models from various bits and pieces, including plasticine, lumps of coal, wire and even a chicken wishbone assuming you could source one. Then we go to the other side of the world and the hot springs of Rotorua, New Zealand, and the British Railways Locomotive Testing Station in Rugby, back in England. There’s an unquestioned gender divide here, as while the girls get to do the modelling and decoration, the boys are the ones who get to see the trains.

Selected Tales from Hoffnung (22:11)

From 1965, with a Play All option, these three shorts are The Hoffnung Symphony Orchestra (7:34), The Hoffnung Palm Court Orchestra (7:12) and The Hoffnung Maestro (7:25). They were made for the BBC (in colour, despite the fact that the Corporation didn’t start broadcasting in colour until 1967). Each was based on the work of Gerald Hoffnung, born in Germany but in the UK following the rise of Nazism and was a cartoonist and broadcaster in the 1950s before his death in 1959 from a stroke at the age of thirty-four. The short cartoons, designed for a ten-minute television slot (in early evening, to attract children and adults alike) were made by Halas and Bachelor, and these three were all produced by John Halas with him also directing one, Harold Whitaker directing another and the two co-directing a third. They’re funny and inventive.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release only, runs to thirty-two pages plus covers. It begins with a spoiler warning, though Hilary and Jackie is a film based on fact and relatively recent fact at that. The opening essay is “Secrets, Lies and Classical Music: Hilary and Jackie” by Rachel Pronger, which leads head-on with the controversy which followed the film’s release. The issue was not so much the story as who was telling it, especially as the key figure was dead, and Jacqueline’s friends seeing the film as a hatchet job. This led to an open letter to The Timessigned by six of Jacqueline’s collaborators. Pronger uses this to lead to a discussion of the relation between truth, memoir and dramatisation and who has the right to tell which story, and points of that Cottrell Boyce’s screenplay is an exploration of that very question, particularly as we see some events from two viewpoints, the second time around with information we weren’t party to previously. Hilary’s section is more conventionally realistic than Jackie’s, which introduces distortion of sound and image amongst other expressionist touches. According to Hilary, the enshrining of her sister as a genius was the destruction of her as a person. Pronger talks about how male-dominated the classical music scene was when Jacqueline was playing – you can see this in archive footage where she’s often the only woman on screen – and how this film is an unusual biopic dealing with such music in that it centres on a woman, and a complex, brilliant one at that.

This is followed by a two-page producer’s note by Andy Paterson (spelled “Patterson” here, at least in the PDF copy sent to review, though it’s with a single T on screen and in the acknowledgements at the back of the booklet). This is a brief appreciation by a “proud father” as he puts it, of a film he revisits after quite a few years. He pays tribute to the cast and crew and thanks the BFI for putting this Blu-ray out in what would have been Jacqueline’s eightieth birthday year. This is followed by Paterson again in 1998, with the film’s original production notes. The booklet doesn’t have a cast and crew listing for Hilary and Jackie itself. It concludes with notes on and credits for the extras, with pieces by Rachel Pronger on Avec Sonia Wieder-Atherton, Katy McGahan on Instruments of the Orchestra, Vic Pratt on Our Magazine No 2, and Jez Stewart on the three Hoffnung shorts.

final thoughts

Hilary and Jackie arrived as a prestigious production in the last years of the twentieth century, a tribute to one of the major exponents of her instrument of that century. She was one whose career and life was cut tragically short, so there are inevitably might-have-beens surrounding both. And there were might-have-beens about this film, immediately controversial amongst the late Jacqueline’s friends and colleagues. What isn’t in doubt is how well crafted a film it is, and particularly how well acted. Despite the lack of involvement of all but one of its principal cast and crew, this BFI Blu-ray release does serve it well.

Hilary and Jackie

UK 1998 | 121 mins

directed by: Anand Tucker

written by: Frank Cottrell Boyce, from the book "A Genius in the Family" by Hilary and Piers du Pré

cast: Emily Watson, Rachel Griffiths, James Frain, David Morrissey, Charles Dance

distributor: BFI

release date: 3 November 2025

- On a personal note, my day job for thirty-four years was in telecommunications and du Pré plc were a regular client. At least at the time, Jacqueline’s cello was their music on hold.[↩]