Une femme douce

Robert Bresson’s 1969 film UNE FEMME DOUCE [A GENTLE CREATURE], his first in colour, is released on Blu-ray from Radiance. Review by Gary Couzens.

After the opening credits, which establish us as being in contemporary Paris, the film opens with a series of shots in typically pared-down Bresson fashion. A hand opens a door. A rocking chair on a balcony tips back and forth and a table overturns, a flowerpot falling to the floor with a crash. The sound of a car screeching to a halt. A scarf floats down the side of the building, as if in slow motion. A woman (Dominique Sanda) lies face down on the pavement, red blood by her head on the paving slabs, having seemingly jumped to her death. The siren of an ambulance. As her body lies in the apartment awaiting the attention of the undertakers, her husband Luc (Guy Frangin) thinks back over their life together…

Une femme douce (sometimes known in English as A Gentle Creature or A Gentle Woman) was Robert Bresson’s ninth feature film. It is adapted from Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novella (just under 20,000 words in the English translation I sourced) A Gentle Creature (Krotkaya) from 1876, its setting updated from nineteenth-century St Petersburg to contemporary Paris. It was also his first in colour, a fact which seems to have surprised people at the time, as if Bresson’s aesthetic needed the minimalist hues of black, white and grey. No doubt there was something of a commercial imperative here. While Bresson was now regarded as a major auteur, even auteurs need to have their films funded (the fact that Bresson made just thirteen features in forty years, plus an earlier short, says nothing so much that his films were hardly commercial prospects, even in France). A better explanation was that black and white had become more or less commercially obsolete in the later 1960s, especially because colour television had by then arrived in Europe, and even directors who played in arthouses had to adapt to the new polychrome world (and the widescreen world, in the case of Ingmar Bergman). While Bresson and his cinematographer Ghislain Cloquet’s use of colour is not as accidental as it may seem, it is low-key and realistic, and not out of keeping with Bresson’s earlier films. The film displays Bresson’s approach to directing – paring things down to essentials, often being more elliptical than other filmmakers might be, shooting the entire film on one lens (50mm, the spherical lens that most approximates human vision) – that he had been developing from his earliest films, shot by various cinematographers. (Cloquet had shot Au hasard Balthazar (1966) and Mouchette (1967) for Bresson prior to Une femme douce, but this was their last collaboration. In 1979, Cloquet took over shooting Roman Polanski’s Tess after the death during production of Geoffrey Unsworth, and they shared the Oscar. Cloquet died in 1981, sadly before he could accept a BAFTA Award for the same film.) The carefully selected soundtrack is particularly important.

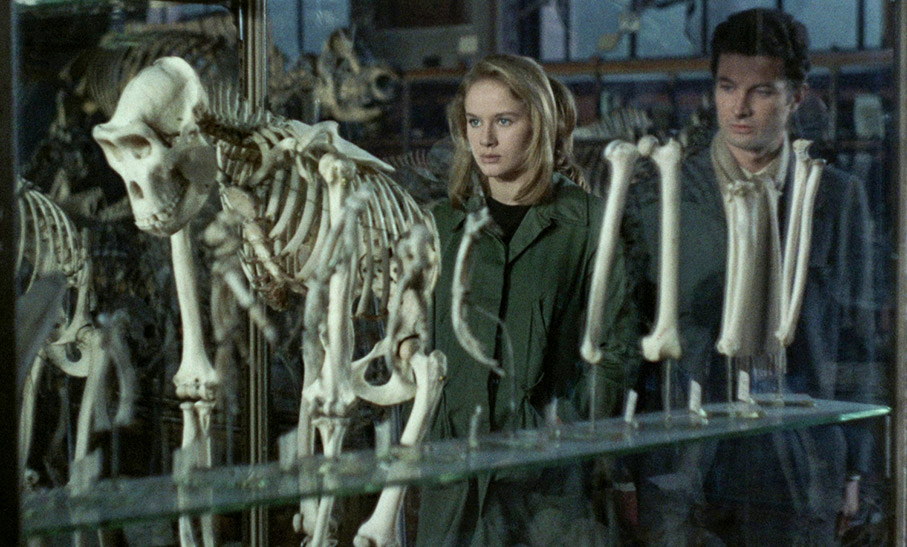

A quick note before continuing.The woman isn’t named in the film’s dialogue (nor is she in the original novella) and there are no character names in the credits. I’ll follow others by referring to her as “Elle” (“she”). As we know from the outset that Elle kills herself, it’s not a spoiler, and the film is an attempt to explore the reasons for this act. Or maybe not, as Luc is unable to reach her. This is one of three Bresson films that explore suicide, a mortal sin in the Catholic Bresson’s theology, following Mouchette and the later The Devil Probably (Le diable probablement, 1977), which treated the subject in such a bleak way that the French censors restricted the film to over-eighteens, in case people were minded to kill themselves after watching it. (Four Nights of a Dreamer (Quatre nuits d’un rêveur, 1971) features someone saved from suicide.) The film concludes that Elle’s actions are largely inevitable, and Luc’s possessive actions are one of the reasons why. He meets her in the pawn shop he runs, where she sells belongings to make ends meet as a student. A marriage proposal follows, then the wedding itself, but the bloom soon goes away. Even her speaking casually to another man provokes his jealousy and he aims to keep control of her.

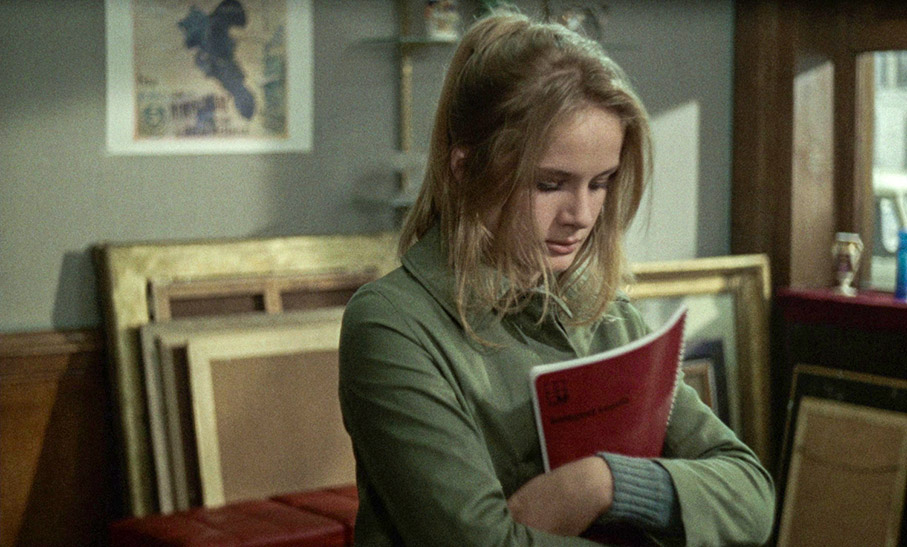

From his fourth feature A Man Escaped (Un condamné à mort s’est échappé ou Le vent souffle où il veut, 1956) onwards, Bresson eschewed using professional actors. The non-pros he did use he referred to as “modèles”, which he coached to remove as much expression from their faces and voices as possible, so no obvious acting. He preferred using amateurs, their lack of previous screen experience giving them a freshness which would no longer apply once they had made the film for him, so he didn’t use them again. He obtained his cast from various places. For example, in Une femme douce, Claude Ollier, who plays the doctor, was a novelist associated with the nouveau roman movement, whose more famous exponents included Alain Robbe-Grillet, Marguerite Duras and Michel Butor. Second-lead Guy Frangin was a painter. Dominique Sanda, seventeen at the time of shooting, was a model who had appeared in Vogue amongst other magazines. She is the great exception among Bresson’s modèles in that she not only went on to a later acting career but stardom, particularly in Italy and her native France. Within a year of this film, her debut, she had acted for Bernardo Bertolucci in The Conformist (Il conformista) and for Vittorio De Sica in The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (Il giardino dei Finzi-Contini), both in 1970. She might have played Maria Schneider’s role in Last Tango in Paris (1972) had she not been pregnant, and occasional sojourns in Hollywood included The MacKintosh Man (1973), opposite Paul Newman.

Une femme douce, which at the time had a distribution deal with Paramount, has been one of Bresson’s more overlooked films, not helped by the fact that it was out of circulation for some time. However, it is available again, and on disc for the first time in the UK, so we can reassess it. It is very much in keeping with Bresson’s work before and since. He returned to updated Dostoevsky with his next film, Four Nights of a Dreamer, which was based on the same novella (White Nights) as Luchino Visconti’s 1957 film Le notti bianche, which coincidentally or otherwise is released by Radiance at the same time as this.

sound and vision

Une femme douce has been released by Radiance on a Blu-ray encoded for Region B only. The film had a AA certificate (restricted to fourteens and over) in British cinemas in 1970 and now has a 15 on disc.

The film was shot in 35mm colour and this Blu-ray transfer is in the intended ratio of 1.66:1. There’s a slight yellowish cast to some of the skin tones but otherwise the colours seem true, including those blues and greens Richard Roud referred to (see below). I hadn’t seen the film before this Blu-ray, but the look of it is in keeping with other late 1960s Eastmancolour films which I have seen on 35mm prints. No issues with the grain.

Une femme douce was monophonic in cinemas and that’s the sound mix on this disc, rendered as LPCM 1.0. Dialogue, the music on the soundtrack and the sound effects are well-balanced, which is just as well as the last-named do a lot of heavy lifting. English subtitles are optionally available and on by default, for the feature and the French-speaking extras.

special features

Commentary by Michael Brooke

Michael Brooke hits the ground running during the opening credits, pointing out along the way the site of a Wimpy, then Paris’s first hamburger fast-food outlet, in late 1968 when the film was shot. He talks about the differences between the film and Dostoevsky’s original story, and the uses of colour (generally blues and greens, citing Richard Roud) and Bresson’s adamance that the film does not contain any flashbacks, rather that we are watching Luc reminisce in linear chronological order. As that Richard Roud example suggests, Brooke draws on a wide variety of Bresson scholarship, books on his work and contemporary interviews with the man himself. Bresson said that he adapted two of Dostoevsky’s shorter works because he thought A Gentle Creature in particular was not one his more successful works. He didn’t want to tackle any of the great (and often very long) novels as they would have been beyond the scope of a feature film of about an hour and a half. Brooke talks about Bresson’s use of modèles, with Dominique Sanda being a unique example of one who went on to a longterm career and a high-profile career at that. He also discusses the two examples of other stories which form sequences in the film – the 1968 film Benjamin, which Elle and Luc watch, and the climax of a production of Hamlet which Elle watches and is critical of – and their parallels in the main film.

Brooke also talks about the other seventeen (count them) screen adaptations, for cinema and television including a Polish animated short, of Dostoevsky’s story, and discusses how Bresson’s work looks on the small screen, especially in VHS days: never any big-screen spectacle (jousts in Lancelot du Lac notwithstanding, though they’re hardly conventionally filmed) and a very “plain” mise-en-scène, but still benefiting from the concentration of a large screen in a darkened auditorium with the carefully-chosen soundtrack doing a lot of work. So Bresson’s films are ideally to be seen in a cinema, but a high-definition restoration on Blu-ray is a good a way to do that otherwise. Brooke keeps going with barely a pause, ending just as the film cuts to black at the end (there are no final credits, not even a “Fin” title) and there’s lots to be gained from this densely-packed commentary.

Interview with Robert Bresson (7:29)

Done for French TV in 1969, in black and white, this interview has a strangely casual format, with both Bresson and interviewer, dancer and choreographer Maurice Béjart facing each other in an empty studio. At this time, Une femme douce was Bresson’s newest film and he talks about his new-found use of colour. The soundtrack receives comment too, with his approach to sound being as musical as if he had plastered the film with non-diegetic music. His approach is that the sounds are interspersed with moments of silence. Béjart suggests this is akin to the minimalist approach of composers like Webern. Given Béjart’s profession, this leads on to a discussion of the role of music and dance, and Bresson’s thoughts of making a ballet film.

Interview with Dominique Sanda (5:29)

From 1987, and seemingly part of a longer interview, Sanda talks about how Bresson first saw her in a magazine when she was working as a model. He then phoned her, and her casting followed in due course. It was a different experience to her later films, in that it was hard to “act”. Her later career was international, and she learned English when working on First Love (Erste Liebe), which Maximilian Schell directed in 1970.

Over Her Dead Body (17:26)

A newly-made visual essay by the team of Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin, the latter narrating over extracts from the film. They discuss the differences other than the time and place settings between the novella and the film, the story being in first person and the film having Luc’s voiceover. While much of the film would seem to be in flashback, Bresson always said that it wasn’t: in Luc’s memory, the difference between present and past is imperceptible. He’s not a reliable narrator anyway, with several places where what he says and what we see don’t match. Álvarez López and Martin invoke Chantal Akerman’s Proust-derived La captive, in its depiction of a woman in a controlled relationship with a man, and there are plenty of foreshadowings of her death being the only solution for her. A useful piece, best watched after seeing the film, though as we know the end of the story at the beginning that limits the number of spoilers.

Image gallery

Twenty-two images, which are separately chaptered so you go forward or back via the keys on your remote. They comprise sixteen lobby cards, three posters and three black and white stills. The posters are French (which makes it a selling point that this is Bresson’s first film “en couleurs”), Czechoslovak and Polish.

Booklet

This limited edition includes a booklet with a new essay by Alex Barrett and an archival interview with Bresson, but this was not available for review.

final thoughts