The razor’s edge

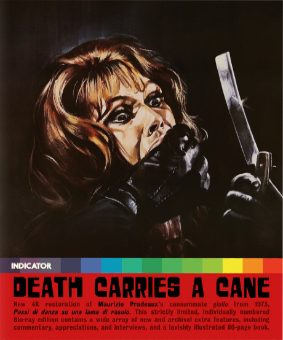

A woman witnesses a murder, and the hunt begins for a serial killer in director Maurizio Pradeaux’s 1973 giallo, DEATH CARRIES A CANE [PASSI DI DANZA SU UNA LAMA DI RASOIO]. Genre fan Gort is in two minds about a lesser seen work whose logic and storytelling issues are balanced out by its dark pleasures, and it looks very nice on Indicator’s new UHD.

It all starts in Rome, where two local jackasses are cheerfully jostling with each other to get a look through one of those pay-to-use telescopes you used to find at scenic tourist spots but that never give you an interesting view of anything. As these two train the telescope on various people and locations, what they see intermittently freezes to allow the opening titles to unfold, concluding on the image of a young woman bending over and displaying her panties like she’s posing for a 1970s Pirelli calendar. It turns out this is one of the jackasses’ girlfriend, and he sees her being picked up by another man. Her boyfriend simply shrugs the whole thing off and departs with his companion to pastures new. What part will these two play in the drama that has yet to unfold? None whatsoever. The telescope, however…

Standing nearby with her mother and priestly father is a young woman named Kitty (Susan Scott, aka Nieves Navarro), a photographer who works solely with a Pentax Spotmatic and a single fixed lens. They’re waiting for Kitty’s boyfriend Alberto (Robert Hoffmann), whom the father handily notes is ten minutes late, a fact that will become relevant later. To pass the time, Kitty pops a coin into the telescope and trains it over the local houses, and while doing so sees a woman being stabbed to death by a black-dressed assailant in an apartment she is only able to identify by the number on the outside of the building. Before she can get a good look at the murderer, the telescope blacks out, and by the time she has jammed another coin into the slot to reactivate it, the killer has fled, seemingly knocking two pedestrians over in the process. Kitty pleads with a passing fireman (Giovanni Pulone) for assistance, but this useless dingbat claims that he can’t stop to help her because it’s his day off and he doesn’t want to upset his presumably ferocious wife. Alberto then arrives and the two attempt and fail to pinpoint the location of the murder, and thus head to the local police station to report the crime. Here Kitty relays what she witnessed to Inspector Merughi (George Martin), who sits behind his desk whittling away at a pencil with a razor blade, seemingly bored at having to listen to the ramblings of this delusional woman.

In case you weren’t aware, or were not clued in by the technically accurate but unexciting and slightly misleading English language title (the original Italian, Passi di danza su una lama di rasoio, translates much more enticingly as Dance Steps on a Razor’s Edge), Death Carries a Cane is an Italian giallo from the early 1970s, and certain elements of what subsequently unfolds are thus set in genre stone. The first and most important is that the individual that we are heavily pushed to believe is the killer will actually prove to be a great big crimson-coloured herring, and there’s a damned good chance that they won’t be the only one we’re invited to suspect along the way. Here, the prime candidate is our Alberto, whose suspicious behaviour is laid on so thickly that the chances of him being the murderer are practically zero. Director Maurizio Pradeaux really goes for broke here. Not only was he not with Kitty when the murder took place, but as the two drive across town and Kitty tries to recall further details of what she saw, Alberto keeps throwing her the sort of looks that suggest he’s genuinely worried about what she might remember. If he isn’t guilty, why would he do this? Beats me. Then there’s whatever it is that Alberto does for a living. Apparently an artist, his speciality is creating cloth and foam mannequins that he then mutilates for Kitty to photograph. He currently has hopes that his friend Marco (Simón Andreu) will put some of them in the live performance show he is putting together, an offer that Marco unsurprisingly declines because thinks they might be a bit too gruesome for his audience. On this score, timing is not on Alberto’s side. When Inspector Merughi pays the couple a visit at their home, Alberto is on the veranda violently stabbing another of his mannequins with a knife. It turns out that the police have finally found the body of the woman that Kitty saw murdered, and Merughi has dropped by to see if she can recall any more information about the murderer. He was dressed in black, she recalls, and had a black hat, “Just like that one,” she remarks pointing to a hat that belongs to – you’ve guessed it – the nervous-looking Alberto. Alberto also has a limp that he claims is the result of a twisted ankle, and when a chestnut seller (Gualtiero Rispoli) who witnessed the killer’s escape has his throat slashed with a razor, the police find evidence that this murderous individual walks with a cane is thus probably lame. And then there’s the short sequence in which a fully clothed Alberto creeps quietly into his and Kitty’s bedroom in the dead of night, softly pulls the sheets from Kitty’s naked body, and photographs her with her own camera. Hell, the police even have a photograph of Alberto partying with the girl that Kitty saw murdered. My God, how can this man not be guilty of these crimes?

But of course, he isn’t. In giallo, the most blatantly obvious candidate is almost never the guilty party. It turns out that the photograph of Alberto with the victim was faked by the police crime lab (bloody good job, boys) purely to test Alberto’s reaction, and in no time at all his genuinely twisted ankle has healed. What seals the deal, however, is when Alberto is contacted by an elderly cleaning woman named Marta (Nerina Montagnani), who after reading in the paper that he was a suspect, phones to tell him that she knows who the killer is and asks him to meet her at her place tonight. Uh-oh, I immediately thought, she’s for the chop. Allow me to elaborate. One of the most popular thriller movie clichés is the supporting character who has information for which the lead character has been searching, and who contacts the lead to arrange a meeting at an isolated location at a later time or date instead of just revealing what they know immediately. In almost every case, the supporting character is killed before that meeting can take place. You could thus colour me surprised when Alberto arrives at the supplied address and is met by a still very alive Marta. She then gives the killer a second chance by informing Alberto that she needs money and will only tell him what she knows if he brings her 500,000 lire, which research suggests was about £220 back in 1973 when this film was made. Alberto agrees and departs, and yep, that’s when the killer shows up, walking across Marta’s roof with their titular cane before appearing in her candlelit apartment and taking a razor to her throat. Tragic though this is, it does effectively clear Alberto of the crime, as if Marta really does know the identity of the killer, then she would have never invited Alberto to her apartment in the first place and would have recognised him as the murderer when he showed up at her door. The audience thus now knows for sure that it can’t be him, and Alberto had the wit to secretly record their conversation and take it straight to Merughi, who a short while later finds Marta’s body. Even Kitty suspected Alberto at one point and tried to quietly pack her bag and leave, and in the most baffling attitude switcheroo in the movie, seems scared of him one minute and a short while later is rolling around in bed with him and gasping with pleasure at his touch. Quite what occurred to convince Kitty of Alberto’s innocence and make her instantly horny for him during the ten second cut-away to a newspaper seller barking out a headline about Alberto being questioned by police is anybody’s guess.

Other giallo staples are also present and correct. We have an anonymous killer of unspecified gender who dresses in a black hat, coat and leather gloves, and who selects their preferred murder weapon from a whole cabinet of cut-throat razors and tests its sharpness out on a piece of paper so we know how lethal it can be. There’s also a string of victims meeting violent and bloody deaths at the killer’s gloved hands, with graphic flesh slicing courtesy of makeup artist Duilio Giustini. Once Alberto is cleared, suspicion is then redirected to another character whom we don’t realise has a limp until later in the film, and another who stops to examine a collection of razors on display in a shop window and is blessed with a naturally shifty face. And then there’s composer Roberto Pregadio’s main theme, a sub-Morricone but otherwise serviceable piece that gets recycled a little too often and plays second fiddle to the electronic single note drones he employs to ramp up the tension.

As the lead detective, Merughi is certainly more proactive than the genre police norm, even if the attempt to give him an interesting quirk by having him always sharpening pencils with a razor blade falls a little flat. Also taking an interest in the case is Marco’s girlfriend Lidia (Anuska Borova), a self-confident reporter with a toothy smile and whose twin sister Silvia (also Borova) seems to exist purely to provide the plot with another quickly disposable red herring, as well as its most its most gratuitous sex scene. I know that at its heart giallo was essentially exploitation cinema, and that tossing in some nudity to spice up the violence was not exactly uncommon, but it’s not often I come across a sex scene so obviously stapled in just to titillate the lads. Following a sequence in Merughi’s office where the Inspector is discussing the case with his assistant Lolli (Rodolfo Lolli, and yes the character has the same name as the actor), the film then cuts to Silvia and her boyfriend Riccard (Luciano Rossi) rolling around naked on their bed to the sort of music that blends romance with porno sleaze, then 60 seconds later cuts back to Merughi’s office, where the Inspector is now conversing with Alberto. And if it’s on-screen sex that you’re after, just remember when this film was made, a time when nudity was deemed acceptable as long as genitalia remained discretely hidden and the sex act involved rolling around in each other’s arms, a bit of bodily kissing, and lots of gasps of ecstasy from the always satisfied women.

Director Pradeaux, whose first giallo venture this was, delivers on the set-piece stalking and killing, but as a cinematic storyteller he sometimes scurries long with scant regard for clarity or even internal logic. It’s probably just me, but I had to watch the film twice to be sure of who was who, how they were related, and exactly what role they played in the story. There is the usual disregard for reality that the vast majority of viewers will probably not care a hoot about (I’d love to know, for instance, the ISO rating of the film that allows Kitty and Alberto to take photos by the dimmest lamplight without a flash), but just occasionally all logic seems to fly out of the window. My favourite example of his comes when Merughi asks Alberto if he realises that he is is being constantly followed. “By your men, I assume?” Alberto responds. “No, Merughi replies, “By the killer.” Spooky, huh? I’ve just one question. HOW DO YOU KNOW THAT?? Did this as-yet unidentified murderer send you a note informing you of this fact, or, more likely, did you deduct this through observational detective work? If the latter and you know for sure that the killer is following Alberto –constantly at that – then you must have seen them doing so. If that’s the case, why the hell haven’t you even tried to arrest them and why do you need to use Alberto as bait to get them to reveal themselves? And it’s not just Alberto’s safety that Merughi is willing to risk for a plan that theoretically should not be necessary. In one of the more credibility stretching moves, he plants a false story in the paper about the bag owned by a sex worker who was a witness to the opening scene crime, then persuades Kitty to pose as the woman in question. Actually, being a product of the sexist end of the 1970s, before asking Kitty he seeks permission from Alberto, who is sure his girlfriend will be fine with the idea. Even with this in mind, why Kitty? Did the Rome police have no female operatives in 1973, women who would be far better trained to react if this risky scheme went belly up?

In the end, Death Carries a Cane is something of a middling giallo, one that should still find favour with genre fans but that is unlikely to convert too many newcomers to the cause. It lacks the sheer style of the likes of Bava or Argento, has a sometimes scattershot approach to storytelling clarity and logic, its sex scenes feel almost like bolted-on exploitation afterthoughts, and the final revelation, when it comes, seriously lacks weight and convincing motivation. Despite this, the quality of component elements still make it a worthwhile watch for genre devotees. The stalking of the victims is often creepily handled, particularly the sequence in which the elderly Marta tours her apartment trying to pinpoint the source of noises from above with only a single candle to guide her, and the one in which American dancer Madga Hopkins (Cristina Tamborra) returns home to sleep unaware that the killer is hiding beneath her bed. Pradeaux is aided considerably here by experienced cinematographer Jaime Deu Casas, whose straightforward framing of the dialogue scenes gives way to some atmospheric nocturnal lighting and expressive angles when the tension is being wound up. There’s even a static shot of Alberto descending a quadrangle staircase after speaking to Marta that looks at first glance like an animated M.C. Escher drawing. If you make allowances for the post-dubbing, the performances are solid, with Susan Scott ultimately making the biggest impression as Kitty, particularly when posing as a sex worker and confronting what may or may not be a dangerous customer, and in the climactic scene, about which I shall say no more.

So that’s Death Carries a Cane, nothing groundbreaking and occasionally a little daffy but still rather engaging and intermittently impressive, especially for fans of this very Italian genre. One thing that did strike me, however, is that for a film that seems keen to keep the identity of the killer a mystery until the final reveal, it does drop a whopping great hint around the halfway mark, a cinematic finger-point that on my second viewing seemed so blatant that I began to suspect a deliberate double-bluff, another manufactured suspicion designed to be quickly discarded alongside all of the others. It’s perhaps because of this, though, that when the killer was finally unmasked, my reaction was an indifferent shrug rather than a wide-eyed expression of startled surprise.

sound and vision

Death Carries a Cane has been released by Indicator on 4K UHD and Blu-ray, and it’s the UHD I’m looking at here. To quote the accompanying booklet:

Death Carries a Cane was scanned in 4K at Augustus Color in Rome using the original 35mm negative. 4K HDR colour correction and restoration work was undertaken at Filmfinity, London, where Phoenix image-processing tools were used to remove many thousands of instances of dirt, eliminate scratches and other imperfections, as well as repair damaged frames. No grain management, edge enhancement or sharpening tools were employed to artificially alter the image in any way.

First up, if you thought those black levels were deep on the recent BFI UHD of Eyes Without a Face, just when until you clap your eyes on the dark of night on this new 4K Dolby Vision transfer, and while at first this can seem a little heavy on the contrast, the far wider tonal range found elsewhere seems to confirm that this was always intended. If you’re looking for a reference quality image, skip to 40:03 and have a look at the impeccable facial close-ups of Alberto and Merughi as they converse in the exterior daylight, which are pin-sharp and beautifully graded with naturalistic colour . One thing the quality of the restoration does reveal, however, is a sprinkling of shots where the focus is a little soft, and in a couple of cases it is profoundly so. Given the quality of the material overall, I’m guessing that this is how the footage looked when it came back from the lab, and with the budget and schedule not allowing room for reshoots, Pradeaux just had to go with what he had. As expected, the print is clean of dust and displays no visible damage, and the fine film grain we all look for on celluloid-shot films is visible throughout. The framing is 1.85:1 and being a UHD there is no regional coding, and according to the Indicator website, the Blu-ray edition is region-free too.

Of the soundtracks, the booklet informs us that audio conform and restoration work on the Italian and English tracks was carried out by Michael Brooke using iZotope RX 10, and both tracks are free of obvious signs of damage and wear, and although there are the inevitable restrictions in the tonal range, the dialogue, effects and music are all clear and distortion-free.

As for which track to choose, with both of them post-dubbed, it once again comes down to personal preference. Much of the dialogue was clearly delivered in English, but as with The Perfume of the Lady in Black, to my ears much of the English language track feels more like the dub it is than the more expressive and committed Italian track. That said, whoever dubbed Merughi on the English language track gets a thumbs-up from me.

Optional subtitles for the hearing impaired are also available, and a third set of English subtitles accompanies the English language track to translate any on-screen Italian text such as newspaper headlines.

special features

Audio Commentary with Eugenio Ercolani, Troy Howarth and Nathaniel Thompson

The team from the Indicator’s simultaneously released The Perfume of the Lady in Black is back for a primarily fact-based commentary that delivers plenty of info on the actors, director Maurizio Pradeaux, co-screenwriter Alfonso Balcázar and editor Enzo Alabiso, as well as the rise, decline and subsequent resurgence of giallo cinema. They note that when it comes to the genre’s internationally successful second wave, it’s impossible to overstate the importance of Dario Argento, and provide some detail on later hybrid giallo-porno movies, a subgenre of which I was previously unaware. There’s plenty of attention paid to Susan Scott, of whom they are all clearly fans, and there is some discussion about specific moments and elements in the film, but there is a sense that they regard Death Carries a Cane as a serviceable rather than an outstanding giallo movie, and at one point it’s tellingly described as “mid-range.”

Eugenio Alabiso: A Life in the Suite (21:19)

The uncredited editor of Death Carries a Cane looks back at his extensive career (he has 185 editing credits on IMDb), recalling how he first entered the film industry and found work as a general dogsbody on productions and an editor on documentaries and sex films before becoming an assistant to editor Roberto Cinquini, with whom he apparently had a great relationship. When Cinquini – who had edited A Fistful of Dollars (Per un pugno di dollari, 1964) for Sergio Leone – died early in the production of Leone’s follow-up, For a Few Dollars More (Per qualche dollaro in più, 1965), Leone replaced him with Mario Serandrei, a talented editor whose lengthy CV has some awe-inspiring highlights1, but whom Alabiso found to be distant and stand-offish. How Alabiso eventually replaced him as editor of Leone’s film is a story best told by him. He discusses his work with several directors, including Sergio Martino and Sergio Corbucci, tells a Leone-based anecdote about the shift from serious westerns to the more comedic tone taken by the Trinity films, and notes that the decline in popularity of Italian westerns happily coincided with the rising success of home-grown crime movies. “Hooray for cinema, that’s what I say,” he says with clear passion. The interview is conducted in Italian with optional English subtitles that are switched on by default, and was made by the commentary track’s Eugenio Ercolani for what looks like the North American Vinegar Syndrome release.

Eugenio Ercolani: The Devil Wears Pradeaux (15:08)

Eugenio Ercolani is back, this time in front of the camera to talk about director Maurizio Pradeaux and Death Carries a Cane. It’s a film he describes as a perfect example of its time, being something of a compendium of prior giallo tropes that lacks the originality and visual style of Dario Argento’s The Bird with a Crystal Plumage (L’uccello dalle piume di cristallo, 1970), and the distinctive personality of Luciano Ercoli’s Death Walks on High Heels (La morte cammina con i tacchi alti, 1971) and Death Walks at Midnight (La morte accarezza a Mezzanotte, 1972). Usefully for those of us new to Pradeaux’s work, Ercolani details some of the key points of a 24-year directing career that only consisted of seven films, a surprisingly small number by Italian cinema standards, and notes that he refused to be interviewed and later did not to care to remember his time in the Italian film industry. He also suggests that he was competent in several genres, and is of the opinion that Death Carries a Cane was probably the high point of his career.

De Sanctis on Pregadio: Symphonies of Sleaze (16:43)

Founder of Italian soundtrack specialists Four Flies Records, Pierpaolo De Sanctis, looks at the career of Death Carries a Cane score composer Roberto Pregadio, from his early work on lowbrow exploitation movies, through scores for films in a wide range genres, to his regular gig as resident conductor and comedy sidekick on the Italian TV show La corrida. His post-WWII embracement of and later return to jazz is also discussed, and while his importance is emphasised at the start, this is undermined a little by the revelation that that his compositions are often labelled as “lounge music,” which De Sanctis describes as “background music that’s not overly distracting but should offer a pleasant accompaniment.” Interesting stuff, and nicely illustrated with film clips, posters and album covers.

Tormentor VHS Opening Titles (3:10)

The opening title sequence of Death Carries a Cane but with the sometimes used English language title of Tormentor. The fact that this has been sourced from a VHS original is presumably an indication of the rarity of this version. Always nostalgic to see those tape blips we used to get on just about every VHS recording we made back in the day.

German Theatrical Trailer (2:45)

An engagingly sinister trailer that’s made even more so by a German narrator who delivers lines like “Fear, just like a nightmare,” and “No-one knows if he is man or beast” as if auditioning for the role of a sadistic Nazi officer in an allied propaganda film from WW2. Works for me, and how could you not love the German title, Die Nacht der Rollenden Köpfe, which translates wonderfully as The Night of the Rolling Heads? Unsurprisingly, as the trailer makers have cherry-picked choice bits from nearly all of the suspense sequences, including the climax, there are some spoilers here.

Image Gallery

52 screens of promotional stills, lobby cards, scanned pages from the German press kit (plus two from what looks like the Italian one), video covers and posters.

78-Page Booklet

The lead essay here is an examination of the film by Italian film critic and film historian Roberto Curti. He clearly holds the film in high regard, and while I can’t quite match his level of enthusiasm, he makes his case really well and I really enjoyed reading his thoughtful breakdown of what, for him, makes the film work. I particularly liked his assessment of dilemma facing Kitty after she witnesses the murder but cannot pinpoint the location due to the flattening effect of the telescope lens – “Kitty is seeing too much and too little at the same time,” he acutely notes.

Next up is a lengthy and in-depth interview from 2008 by José Luis Salvador Estébenez with actor Nieves Navarro, who worked for some time under the pseudonym Susan Scott, which she is credited as on Death Carries a Cane. Navarro made a lot of films, and although several key titles are covered, Death doesn’t get a mention, being one of a string of giallo movies that earned her the Queen of Giallo nickname that she dismisses here. This is a most informative and enjoyable read with a couple of surprises, my favourite being when Navarro names her favourite giallo film, and it’s not one of her own or even an Italian production, but David Fincher’s Se7en (1995).

This is followed by an equally thorough and equally fascinating interview with actor Jorge ‘George’ Martin, conducted by José Luis Salvador Estébenez in 2020 for the website La Abadía de Berzano. If all that was discussed here was Martin’s journey from professional gymnast to stunt man to leading man and eventually director this would be interesting enough, but Martin has had a remarkable life that is peppered with extraordinary stories that I’m not about to spoil here but that make for sometimes eye-widening reading.

After this, we have an interview with actor Robert Hoffmann, conducted in 2000 by Michael Cholewa and Karsten Thurau for Terrorverlag. Although not quite as extensive as the two preceding interviews, this is still an educational and engaging read, and Hoffmann has his share of surprising stories, from his first experience of filming in Hollywood to the accident that almost ended his career.

Full credits for the film and details of the restoration and transfer (see above) are also included, and the booklet is handsomely illustrated with photos, promotional artwork, and even a scan of an Italian newspaper story that is relevant to the George Martin interview.

final thoughts

Not top-drawer giallo, perhaps, but entertaining nonetheless, despite its logic holes and sometimes hurried storytelling, but there’s still enough in Death Carries a Cane to keep us genre fans relatively happy, and it’s great to see a lesser known example of the genre getting such a careful restoration. For giallo devotees, this disc definitely comes recommended, for the transfer and for the typically excellent special features, including an excellent accompanying booklet.

Death Carries a Cane [Passi di danza su una lama di rasoio]

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

- Serandrei’s whopping 269 editing credits on IMDb include Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio, 1960), Black Sabbath (I tre volti della paura, 1963) and Blood and Black Lace (6 donne per l’assassino, 1964) for Mario Bava, Rocco and His Brothers (Rocco e i suoi Fratelli, 1960) and The Leopard (Il gattopardo, 1963) for Luchino Visconti, the portmanteau film Boccaccio ’70 (1962) for Vittorio De Sica, Federico Fellini and Mario Monicelli, and The Battle of Algiers (La battaglia di Algeri, 1966) for Gillo Pontecorvo[↩]