Taking the fall

Things go rapidly downhill for an honourable samurai when he agrees to take the blame for the crime of another to protect his clan in THE BETRAYAL [DAISATSUJIN OROCHI], Tanaka Tokuzō’s compelling and sometimes thrilling blend of jidaigeki drama and superbly staged chanbara swordplay. Slarek sides with the betrayed on Radiance’s welcome recent Blu-ray release.

Right, there’s a lot of plot description ahead and a fair few Japanese names to remember, so grab a coffee and get comfortable, and let’s get to it.

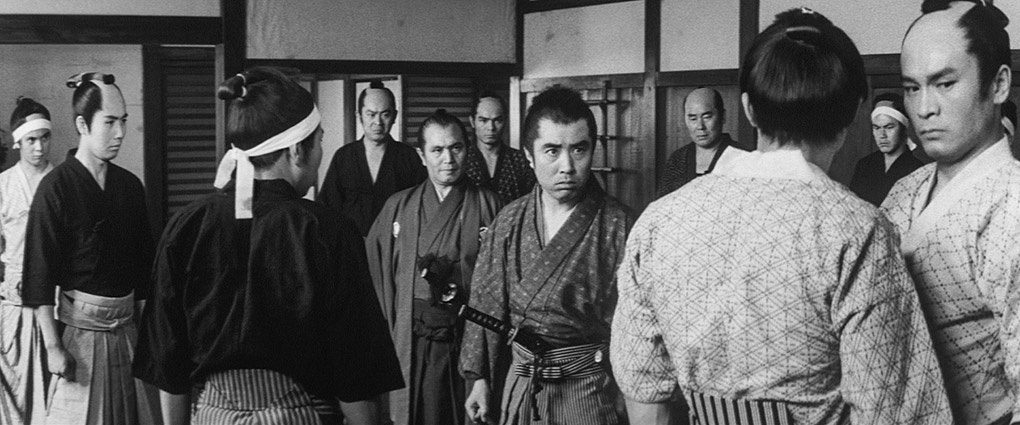

In an unspecified district in samurai-era Japan, Kashiyama Denshichiro (Gomi Ryūtarō), a prominent and arrogant member of the powerful Iwashiro clan, rides noisily into town and strides into the Isaka Jigen-ryū dojo run by the neighbouring Minazuki clan with whom the Iwashiro clan has an alliance, and demands a fencing lesson. He is met by assistant instructor, Kobuse Takuma (Ichikawa Raizō), who informs him politely that that the head instructor is unavailable and that day’s training has already concluded. Denshichiro announces that he’s heard there is an expert in Jigen-ryū swordsmanship at the dojo, which is quickly identified as Takuma, but when he demands that Takuma draw his sword, the level-headed assistant instructor calmly declines.

Angry at having his demands rejected, Denshichiro rides furiously away, but en route back to his home he encounters two Minazuki samurai in the shape of Katagiri Mannosuke (Hiraizumi Sei) and Makabe Jurota (Nakatani Ichirō) and pauses briefly to mockingly accuse the Minazuki clan of cowardice. The furious duo give chase and a brawl ensues, but when Denshichiro contemptuously attempts to laugh the whole thing off, the furious and impetuous Mannosuke strikes him down from behind with his sword. Aware that the seriously injured Denshichiro has seen their faces, Jurota encourages the startled Mannosuke to finish the man off, but before either can act, the approach of a pair of merchants prompts them to hide in the bushes. The mortally wounded Denshichiro takes this opportunity to struggle to his horse, climb aboard, and head for home.

The next day – which is cut to immediately in the one of the film’s many waste-free time-jump edits – a samurai named Kashiyama Matagoro (Naitō Taketoshi) storms into the Minazuki dojo and demands the head of the man who killed his brother. He is met by master swordsman Isaka Yaichiro (Uchida Asao), who keeps a cool head and encourages the angry Matagoro to calm down. Matagoro reveals that his brother was dead before he reached home but he knows for a fact that he was at this dojo the previous day, and is convinced (rightly, as it happens) that one of the Minazuki samurai was responsible for his murder. “You stabbed my brother in the back!” Matagoro angrily shouts at the gathered samurai. “There is nothing more dishonourable than to attack a man from behind.” Ah, yes, honour. We’ll be coming back to that soon. The still calm Yaichiro decides to hear Matagoro out and leads him to a back room so the two can converse in private. As he does so, Jurota tells the nervous Mannosuke to keep his mouth shut.

When you’re watching the film for the first time and not red-hot on face recognition, this is where those time-jump edits can start to get a little disorientating for non-Japanese viewers. The first of these transports us in a blink to later the same day, where a differently dressed Mannosuke is reporting the details of the incident to clan elder Taihei (Shōzō Nambu), whom we quickly discover is Mannosuke’s father. Taihei realises that this could quickly become a serious problem for their clan – “We may never recover from this,” he muses. It’s then that Mannosuke breaks down and confesses that he was the one who killed Denshichiro and offers to surrender to the Iwashiro clan. Despite his anger at Mannosuke’s stupidity, Taihei is all too aware that he is the Katagiri family’s only son and heir and decides he needs to speak to the Iwashiro clan’s chief advisor, Takagura Kageyu (Araki Shinobu) about this matter. The next second he’s kneeling before the angry Kageyu and attempting to find a resolution to this potential inter-clan conflict that doesn’t involve handing over the killer. Correctly suspecting that he’s trying to protect someone, Kageyu tells him that he has an alternative suggestion that he thinks will satisfy the honour of their domain.

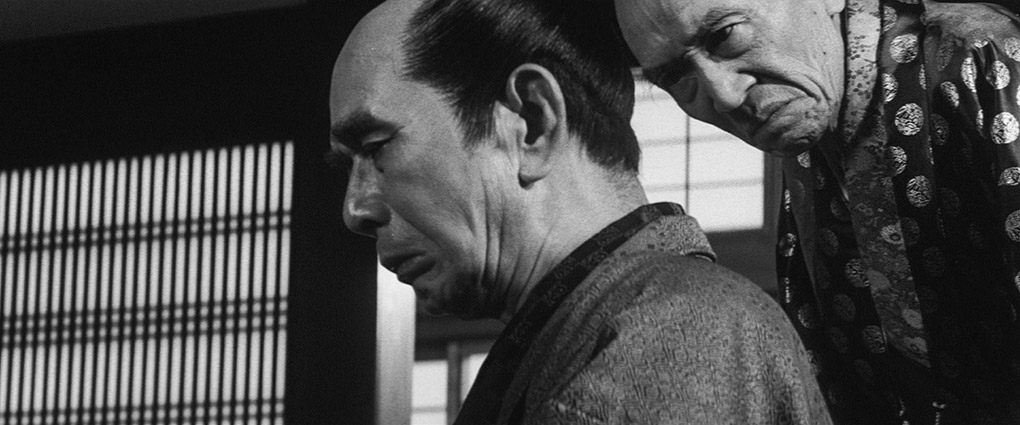

Before we can hear it, there’s another temporal and location jump that is so sublimely executed that deserves a special mention. As Kageyu is about to reveal his suggestion to Taihei, the camera is framed on a close-up of the left side of the nervous and kneeling Taihei’s face, with Kageyu leaning into shot to address him. We then seem to cross the line of action to focus at the right side of his face instead, and it took me a couple of seconds to realise that we were in a different location and that I was looking at Taihei’s brother Handayu (Katō Yoshi) instead, who is wearing an identical expression as he apprehensively kneels while Taihei walks around vocally contemplating the situation at hand.

It’s here we learn that the offer made by Kageyu was for the guilty party to be exiled for a year instead of being executed for his crime. Taihei is not convinced that this will work, and when asked by Handayu if they know who the murder is yet, Taihei flatly denies that they do, but states that there could be grave consequences if they fail to produce the individual. It’s a problem that clearly causes Handayu considerable worry.

Shortly after this we meet Taihei’s attractive daughter Namie (Yachigusa Kaoru) and her husband-to-be, who is none other than assistant instructor and Jigen-ryu expert Kobuse Takuma. The two are obviously happy and looking forward to their nuptials the following Spring. They are then joined by Handayu, who asks to speak to Takuma and for some reason insists that his daughter hear what he has to say as well. Having mused for some time on the potentially catastrophic effects that failing to find Denshichiro’s killer will likely have on their family and their clan, he asks Takuma if he will admit to being the murderer and self-exile for a year, during which time he pledges to find a way to smooth things over with the Iwashiro clan and allow for his safe return. “If I should fail to convince them,” he pledges, “I’ll cut my belly and clear your name.” After soberly weighing the consequences of this action, Takuma’s sense of honour prompts him to agree to Handayu’s request, despite the distress that it causes Namie. Unaware that Jurota is eavesdropping just outside the door, Handayu tells Takuma that he should meet him in the Spring at their lodgings in Jōshu Takashi to arrange his return, and that he should tell no-one of their arrangement and leave as soon as possible, which Takuma does. A deeply honourable man is willing to sacrifice his immediate happiness, his reputation and his safety to protect the family of an equally honourable man and the clan to which they have both dedicated their lives. Such is the code of a true warrior. What, you may ask, could possibly go wrong? If you know your 1960s jidaigeki movies, the question will likely not be what, but how soon it will happen and how bad things will get for Takuma. It’s a testament to the film’s tightly economical approach to storytelling that six paragraphs of set-up plot occupy a mere 17 minutes of this 87 minute film.

The Betrayal [Daisatsujin Orochi] is a prime example of what I tend to think of – for want of a better term – as anti-Bushidō cinema, Japanese films from the 1960s that directly challenged traditional notions of samurai honour, prime previous examples of which include director Kobayashi Masaki’s 1962 Haraki [Seppuku] and Imai Tadashi’s 1964 Revenge [Adauchi]. Both are brilliant but emotionally punishing films in which decent and honourable individuals suffer at the hands of corrupt and duplicitous men, most of whom are in positions of authority within the samurai ranks. As written by Hoshikawa Seiji and Nakamura Tsutomu – from an original idea by Susukita Rokuhei – and directed by Tanaka Tokuzū, The Betrayal, I would posit, is every bit their equal, in execution as well as the punishment that its nominal hero suffers on his downward journey to a climactic confrontation that genuinely dropped my jaw. I’ll be getting to that, and touching on the misfortunes that plague poor Takuma in the paragraphs ahead, so if you’ve not seen the film and wish to experience this without foreknowledge, then I’d advise hopping ahead to the final paragraph of this review or click here to do so automatically.

Any hopes that the falsely disgraced Takuma will land on his feet are quickly dispelled when he is walking alongside a river and sees a child fall in the water. His humanitarian instincts instantly kick and he strips off his robe and sword to jump in and rescue the boy, an opportunity that a previous hidden scoundrel named Funajiro (Fujioka Takuya) takes to steal the samurai’s wallet, leaving him without a penny to his name. It’s then we get the big one, which I suspect that that anyone familiar with this downbeat subgenre of the jidaigeki movie will likely see coming even as they secretly hope it won’t occur. As winter arrives and the unwell Okuma continues to worry about what Takuma must be going through, Handayu reveals that negotiations with the Iwashiro clan are not going as well as he had hoped. He then tells Okuma not to worry and to trust her father, then steps outside, has a heart attack and dies, and with him perishes the promise he made to Takuma to clear his name. The only people left who know that Takuma is innocent of the crime are Mannosuke and Jurota, for whom Takuma has become a handy scapegoat, and Okuma, who as a woman in a strongly patriarchal society would not be believed even if she were reckless enough to speak out in support of her fiancée.

From this point on, it’s a downhill slide for the unfortunate Takuma. Having lost his wallet, he’s reduced to joining a road-building work gang, where he’s confronted by a sadistic governor and beaten by his men. Soon, not only are the Iwashiro men trying to kill him, but he’s also being hunted by members of his own clan, who, under the new stewardship of the unsympathetic Ochiai (Toda Akihisa), believe it is important for their standing that they be the ones to claim Takuma’s head. If that wasn’t enough, a second confrontation with that sadistic governor results in Takuma reacting to an act of cruelty on the man’s part by instinctively drawing his sword and striking him dead, which casts him as an outlaw and sees his name and face painted on wanted posters across the region. He’s repeatedly recognised and challenged by foes and former allies alike, and at one point is rescued from injury by a woman named Shino (Fujimura Shiho), whose motives turn out to be less about attraction than the empathy of a lonely woman for this unfortunate man’s fate. Even this small beacon of hope for Takuma’s future is ultimately crushed by the cruelty of amoral men, while his later charitable gift to a couple contemplating suicide due to financial pressures proves to be an ultimately futile gesture. And all this is just a sampling of the misfortune visited on Takuma.

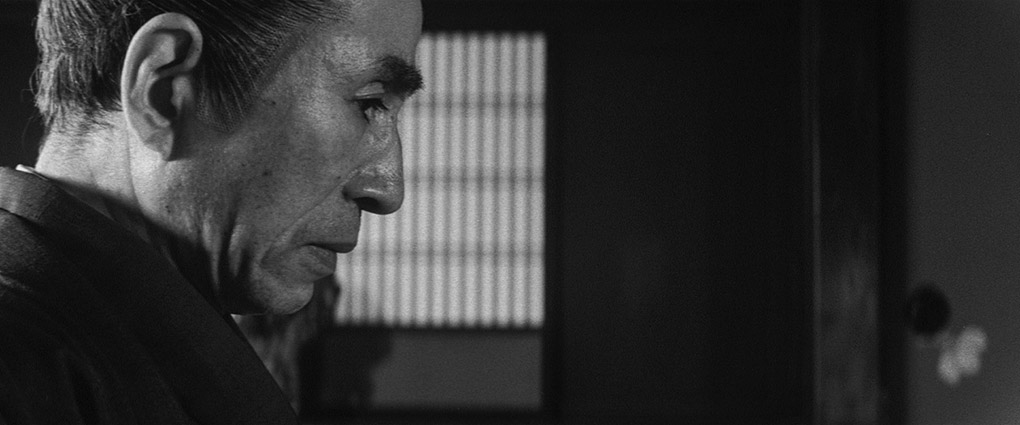

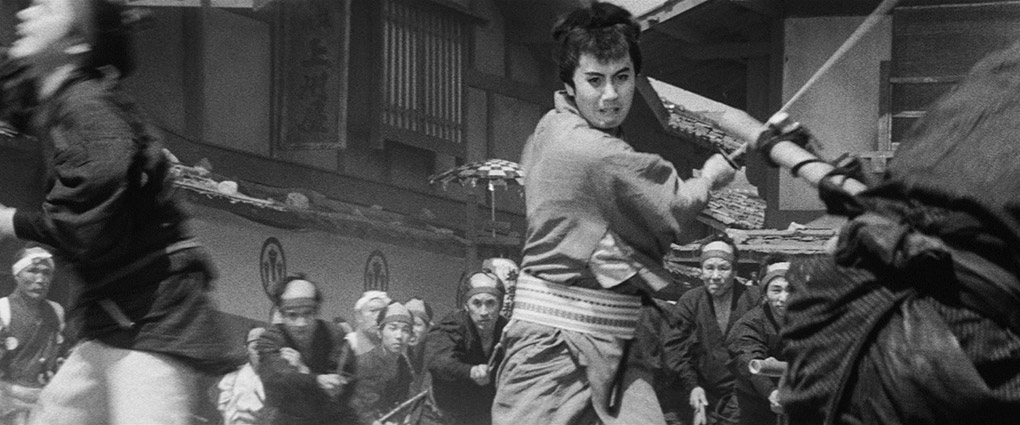

The downbeat tone is intermittently lightened when chance sees Takuma cross paths again with Funajiro, who, on realising that Takuma doesn’t realise that he’s the man who stole his wallet, elects to join him on his travels. For a while, it seems as if this jovial rogue will be on board as an intermittently mood-uplifting sidekick, and to a degree he is, but it’s not long before it becomes evident that even at his friendliest, Funajiro’s motives are purely mercenary. The tone also shifts when Takuma is forced to do battle against the men of both clans when they try to take him down, superbly staged action sequences that are integral to the drama and remain reality-grounded. Takuma’s ability to take down multiple opponents without suffering a scratch is signalled from the very start by his identified status as a master of Jigen-ryū swordsmanship, a fighting style whose emphasis is on delivering the killing blow in a single strike. It’s perhaps a tad ironic that the first demonstration we get see of Takuma’s considerable skill comes when he keeps his scheduled appointment at Jōshu Takashi, unaware that Handayu has passed away. Here he is ambushed by Ochiai and his men, and after the slimy Jurota – who had previously admitted to Takuma that he overhead the conversation between him and Handayu – refuses to back his claim that he is innocent of the crime, he has to fight and hide to escape with his life. As he falls exhausted into reeds at sunset, he delivers what is effectively the coda of the film: “A samurai’s word… is meaningless! It’s ugly and mean! How absurd. And foolish. Samurai honour? Does such a thing exist? No. It doesn’t. There is no such thing!”

Utterly compelling although the drama is, these albeit brief combat sequences are excitingly staged highlights, impeccably staged fights that are always choreographed with the placement of the camera in mind. Repeatedly, Tanaka cuts to a wider viewpoint to watch a string of moves executed in a single shot, which are positioned and directed so that it always appears as if Takuma’s sword makes full contact with the opponents that he cuts down, despite them coming at him from various directions. Terrific though these sequences are, nothing prepares you for the genuinely astonishing 15-minute climactic battle, which pits Takuma against insanely impossible odds, as swordsmen from both clans and from law enforcement line up outside the inn in which his presence has been betrayed, like an army of troops preparing to do battle with an entire regiment of opposing forces. All this for one man? You’d better believe it. I have no problem describing what unfolds as epic, a brilliantly choreographed, performed and filmed one-against-a-couple-of-hundred fight for survival in which Takuma is attacked not just with swords, but with ladders, wooden panels, ropes and carts in a coordinated attempt to entrap and disable him. Amazingly, Takuma never comes across as a superhero warrior here, just a highly skilled swordsman running on adrenaline and desperation, convinced he is going to die but determined to take down as many of those who have wrong him and turned against him as he can before he finally falls. It’s a driving force that is perfectly captured by a momentary pause after Takuma’s sword breaks and he has to physically prise open the fingers of his right hand to free the weapon, so tightly has he been gripping it by then. The sheer physical demands that this puts on Takuma is also acknowledged in the building exhaustion that repeatedly floors him and which he has to continually try to shake off to survive.

While I’m not going to talk about how the film ends, I will admit things didn’t play out quite as I was expecting and I was left with a fair few question that I’m personally fine with the film itself not answering. It rounds off one of the most astonishing climactic scenes I’ve seen in Japanese film of any period, one that in its scale and scope even outstrips the brilliantly staged climactic battles in the aforementioned Harakiri and Revenge. Tanaka’s use long takes, isolating wides, telling close-ups, smooth camera moves and even shot reframing zooms enables him to tell his story at a brisk pace without the filmmaking itself ever feeling hurried. He’s ably served here by Suganuma Kanji’s tight editing and Makiura Chikashi’s superb scope monochrome cinematography, which repeatedly makes full use of the 2.35:1 fame to position multiple characters in a single shot and subtly imply their relationship to each other and/or the current location. A highlight on this score is also one of the film’s most deliberately frustrating moments, as the camera glides around the contemplative Takuma as he sits atop a hill with Funajiro and turns to casually observe the transport of two sedan chairs on the distantly located road below as it slides into shot, unaware that the unwell Namie is tied up in one of them.

Having not before been even aware of The Betrayal, I was intrigued by its premise and the fact that it was directed by the man who had helmed Shinobi 4: Seige (Shinobi no mono: Kirigakure Saizo, 1964), The Snow Woman (Kaidan yukijorō, 1968), The Demon of Mount Oe (Ooe-yama Shuten-dōji, 1960), and The Haunted Castle (Hiroku kaibyô-den, 1969), all of which I hold in the highest regard (they’re all also available on Radiance Blu-ray, the last two as part of the newly released Daiei Gothic Vol 2). As I think I’ve made clear, I was utterly captivated by the film from its briskly paced opening scenes, by the unjust fate that is visited on Takuma and his downward spiral from honourable samurai to luckless ronin outlaw, by the committed performances, and by Tanaka’s impeccable handling. But it’s that astonishing final fifteen minute finale that sticks in the memory, as brilliantly staged, insanely ambitious, impossibly imbalanced but strangely believable one-against-an-army battle as I’ve ever seen.

sound and vision

To quote the accompanying booklet:

The Betrayal was transferred in High-Definition by the Kadokawa Corporation and supplied to Radiance Films as a High-Definition video file.

Unfortunately, that’s all the information we have, with no details of the restoration that has obviously been undertaken here. The film is presented in its original aspect ratio of 2.35:1, and on the whole looks really good, with well-defined detail that is, as is so often the case, most pronounced on close-ups. On interior scenes, the contrast grading is on the punchy side, with black levels so beefy that it sometimes feels as if some detail is being swallowed, though on the exterior scenes, particularly those where fill-in lighting or reflectors were used, the grading feels spot-on, and the best material is first-rate. There is a very faint level of brightness flickering on some scenes that is common on restorations of older films, but this is barely noticeable and in no way distracts. The film grain is fine but it’s definitely there, and the image is clean of dust, dirt and damage. An impressive transfer for a film that had almost fallen off the cineaste radar.

The Linear PCM mono 2.0 soundtrack does show its age in the limitations of its tonal range, but not in a manner unusual for a film of this vintage. There is some minor loss of integrity in the louder portions of Ifukube Akira’s carefully rationed score, but all of dialogue and sound effects are clear, and the track itself is otherwise free of damage and wear.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default. Pleasingly, Japanese names are translated here exactly as they are spoken, with family name first instead of the usual habit of reversing them so that they conform to western convention of family name last.

special features

Selected Scene Commentary with Tom Mes (41:23)

Rather than deliver a full-length commentary, respected Asian cinema writer and expert Tom Mes has instead elected to comment on four sequences, chaptered segments that he uses as jumping off points to discuss various aspects of the film, its director, and its visual style. Each of these can be watched individually or all together in sequence, the running time for which is noted above.

The Samurai Film (15:54) runs under the plot-busy opening 15 minutes, during which Mes reveals that this film is effectively a remake of the 1925 silent film Orochi [The Serpent] by pioneering director Futagawa Buntarō, a work that he examines in some detail and compares to Tanaka’s film. He notes that the views of the wave of directors who were questioning the traditional samurai code in the 1950s and 60s were coloured by their experiences in WWII and the militaristic use to which that code had been put, and that the wave itself was effectively kicked off by the Kurosawa Akira double of Yōjimbō (1961) and Sanjūrō (1962). He also praises the Radiance Blu-ray releases of Tanaka films (they certainly get my vote) and tantalisingly suggests that there are more to come.

In Japanese Film Studios (7:39), Mes discusses the Japanese studio system of the day, and how the individual studios favoured specific actors and would cast them repeatedly in their productions, which frankly sounds no different to the Hollywood system of the 1930s and 40s. He also suggests a link between the breakup of that system to the premature death of hugely popular star Ichikawa Raizō, who died of cancer at the tragically young age of 37.

In Anatomy of a Duel (14:25), Mes cites film scholar David Bordwell’s assertion that pre-war Japanese cinema was effectively broken into three styles, which Mes handily outlines and relates directly to this film and especially its extraordinary finale. He notes that Tanaka is generally regarded as an apprentice of the great Mizoguchi Kenji, and that while The Betrayal was once seen as little more than a B-movie, this new restoration has enabled it to be reappraised as one of the greats to stand alongside the likes of Sword of Doom [Dai-bosatsu tôge] (Okamoto Kihachi, 1966),Harakiri, Yōjimbō and Sanjūrō. Once again, I find myself on the same page as Mes here.

In the final segment, The Grapes of Samurai Wrath (3:29), Mes explores how the lopsided logic of the samurai world was worked into this film, and discusses the decision to cover a key climactic moment in wide shot and the fact that we never discover the fate of the individual whose actions launched the chain of events that led to Takuma’s downfall.

This is all typically fascinating stuff from the always-excellent Mes, though I do have a feeling that by the end, his commentary was out of sync with the action on screen – he ends the final segment by seemingly observing what happens in the film’s final shot, which at this point in the on-screen action is a good 15 minutes away. It matters little, as the topics under discussion are only occasionally specific to on-screen events and make for compelling listening regardless, and it’s always possible I’m way off on this.

The Path to Betrayal (9:40)

Film writer and critic Philip Kemp looks at the work of directors Futagawa Buntarō and Tanaka Tokuzo, and directly compares Orochi to The Betrayal, which he regards not as a remake but an adaptation that draws on a similar central theme. This is one of those special features that crop up intermittently whose author and narrator finds the exact same things to praise that I’ve highlighted in my review, even at one point citing the same line of dialogue. Clearly what resonated with me about the film also impressed the learned Mr. Kemp.

The Four Elements of Tanaka Tokuzō (9:22)

Working well as a companion piece to his scene-select commentary track, this video essay by Tom Mes takes a chaptered look at the recurring characteristics of the films of Takana Tokuzō, exploring the use of mist, earth, fire and time in the director’s films, extracts from several of which are included here. Another informative and highly engaging inclusion.

Also included is a 20-page Booklet featuring an essay by author Alain Silver, whose many written works include The Samurai Film. This is a hugely knowledgeable, well-researched and engagingly written piece that looks at the history of the disillusioned samurai in various media and the sadly short career of actor Ichikawa Raizō, before moving on to a perceptive examination of The Betrayal. The main credits for the film and details of the transfer have also been included.

final thoughts

In case you skipped to the end to avoid spoilers or I somehow haven’t already made this clear, I was knocked out by The Betrayal, a gripping if downbeat jidaigeki drama with a spattering of impeccably staged swordfights that evolves in its jaw-dropping finale into a full blown and superbly executed chanbara action movie. It’s well served by Radiance’s Blu-ray release, which features a strong restoration and transfer and a small but very well targeted collection of special features. For genre fans, it’s an absolute must, and thus comes highly recommended.

The Betrayal [Daisatsujin Orochi]

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

The Japanese convention of family name first has been used for all Japanese names in this review.