Cinema Expanded: The Films of Frederick Wiseman

Five early films from the great American documentarian, CINEMA EXPANDED: THE FILMS OF FREDERICK WISEMAN, is a three-disc Blu-ray set from the BFI. Review by Gary Couzens.

Frederick Wiseman is one of America’s finest documentary filmmakers. He has also been prolific, after a relatively late start in his mid-thirties with Titicut Follies in 1967, he has made forty-four feature-length documentaries until his most recent and likely final one, Menus-Plaisirs: Les Troisgros in 2023. Not always without controversy (especially in the case of Titicut Follies), his films often take us inside institutions of public life. Those are especially American institutions and American public life, though later films venture abroad, for example to London (National Gallery, 2014) and in several cases France.

Wiseman was born on New Year’s Day 1930 and is still with us as I write this. He was working as a law teacher at the Boston University Institute of Law and Medicine before becoming a filmmaker. His first experience with film was as producer of The Cool World (1963), directed by Shirley Clarke.

Much of Wiseman’s funding has come from the US Public Broadcasting Service (PBS), where many of his films have been shown. That has also been the regular home of another major American documentarian, Ken Burns. However, the work of Burns, twenty-three years younger, is very different, while being equally deep dives into particular subjects, often especially American ones. Burns employs a narrator (often Peter Coyote) and actors reading out letters and other text, while making up his stories by means of archive material, moving pictures and still photographs, mixed with interviews to camera by participants and experts. Like Wiseman’s films, Burns’s may have lengthy running times, but they are divided into episodes of between one and two hours each.

Wiseman’s films are very different. There are no captions, no narration, no non-diegetic music (though High School is an exception to this). The camera is seemingly objective, capturing its reality from a presumably reasonably unobtrusive place. However, “objective” is misleading: after intensive shooting, the films are constructed in editing (done by Wiseman), and the order of sequences and cuts are used to make the films’ points. The films bear out Jean-Luc Godard’s dictum that drama and documentary are closer than you might think: a drama (well, a live-action one) is a documentary recording of people and places at the time of the film’s making, while documentary is as structured and heightened as any fiction. The people we see in these films gave their consent to be filmed (or consent was given by the institution concerned, in the case of Titicut Follies) but they don’t seem aware of the camera. Presumably any shots where someone was aware of the camera and possibly playing to it didn’t make the final edit. At the beginning of his career, Wiseman was associated with the Direct Cinema movement, along with such filmmakers as the brothers Albert and David Maysles (Salesman (1969), Gimme Shelter (1970, co-directed by Charlotte Zwerin) and Grey Gardens (1975)) with an emphasis on lightweight 16mm cameras and direct sound, and at least an outward objectivity – though as Wiseman says his films actually have no such thing.

Wiseman’s earliest films, including the five in this set, were shot on 16mm film. They are in black and white almost certainly due to the need to shoot in available light, as black and white stock then was more sensitive than colour. The Store (1983) was his first feature documentary in colour, though he returned to black and white twice more that decade with Racetrack (1985) and Near Death (1988). Later films have been digitally-captured. The length of the films may be down to the material amassed by Wiseman and his small crew during shooting, but our immersion in his subject matter can lend itself to lengthy running times. The first three in this set run to between an hour and a quarter and an hour and a half, with the other two coming in at just under two and a half and just over two and three quarters. However, Wiseman has made films of three or four hours in length, with Near Death being his longest at five hours and fifty-eight minutes.

It’s fair to say that Wiseman’s profile has been higher in his native country than in the one this site is based in. However, some of his films have turned up over here, particularly on television. In August 1986, Channel 4 had a mini-retrospective of four films: Hospital (included in this set), Essene (1972), Basic Training (1971) and Law and Order (1969). The same channel devoted an evening to Near Death, beginning at 9.15pm on Saturday 30 March 1991 and ending in the early hours of Sunday, British clocks having gone forward an hour during the broadcast. That is as far as I can determine the longest film shown on British television in a single timeslot and uninterrupted except for commercial breaks. Meanwhile, BBC2 held what it billed as the world television premiere of Titicut Follies on 27 March 1993 (though it had been shown on PBS before that, see below). I saw that showing, having seen the film before at what was then the National Film Theatre. Others of Wiseman’s films have had showings on the BBC over the years.

TITICUT FOLLIES

Wiseman had taken his university law class to visit Bridgewater State Hospital in Massachusetts. Bridgewater was and is an institution for the criminally insane, opened in 1855. After producing The Cool World, Wiseman had an urge to direct his own film and contacted the hospital, submitting a proposal. After nearly a year of negotiations, permission was granted. Facility staff had to be present at all times, and could determine there and then if any inmate was competent to be filmed or not. Also, the hospital’s most famous inmate, Albert DeSalvo, the Boston Strangler, was not to be filmed. In fact, DeSalvo escaped with two others in February 1967. He turned himself in three days later, saying that he wanted to highlight the conditions in the hospital, something that Wiseman’s film was prevented from doing for a quarter of a century.

Titicut Follies was shot in twenty-nine days, with a small crew, Wiseman being his own sound recordist and his cinematographer being ethnographic filmmaker John Marshall. Wiseman also edited the film, taking a year to do so, after hours at the television station WGBH-TV in Boston. It was scheduled to premiere at the 1967 New York Film Festival, but then the trouble started. The state government of Massachusetts tried to raise an injunction banning the film, claiming that the patients’ privacy and dignity had been violated, as several of them were shown naked, although Wiseman had gained permissions from everyone shown on screen, including from the hospital itself as it was its inmates’ legal guardian. (It’s worth mentioning that full-frontal male nudity and occasional strong language was not something that most filmgoers were used to seeing on screen in 1967. The controversy began when a social worker saw the film and wrote to the Massachusetts State Governor expressing shock at some of the scenes.) The New York showing went ahead, but the following year, the film was withheld from any distribution and all copies were ordered to be destroyed. On appeal to the Massachusetts Supreme Court, the film was spared destruction, but it was only allowed to be shown to the medical, legal and social-work professions or students in these fields. This remained the case for two decades. Titicut Follies became the first film banned in the United States for reasons other than obscenity or national security. Wiseman went on record to say that he felt the film was being suppressed to protect the state’s reputation.

Given that Titicut Follies was Wiseman’s first film, and he had not directed before, it’s remarkable how much of his characteristic method was already in place. As so often, with the lack of any voiceover or captions, points are made via the editing. Some of them are a bit more on the nose than in later Wiseman films: for example, a naked patient being force-fed via a nasal tube is intercut with the same patient being shaved, made up and, in a suit and tie, put away in a morgue drawer. Later films would tend to have more descriptive titles, but here “Titicut Follies” is the name of a revue put on by patients, which gives the film its opening and closing scenes. “Titicut” is the Native American (Wampanoag) name of the Taunton River, near to the hospital. Nearly sixty years later, the film has lost none of its impact.

Titicut Follies remained suppressed until 1987, when the relatives of seven inmates who had died at Bridgewater sued. They made the case that if Wiseman’s film had been available the brutal conditions – bare cells, inmates forcibly stripped naked, infrequently bathed, force-fed – would have become known and maybe their clients and others would not have died. In 1991, the Superior Court allowed Titicut Follies to be publicly available as the First Amendment overrode privacy concerns, which were moot anyway as most of the inmates seen in the film were dead by then. The State Supreme Court ordered a statement to be added to the effect that changes and improvements in the institution had taken place since the film was shot in 1966. This is at the end of the film, and it’s hard to miss the sarcasm in the way it is placed. So, in Wiseman’s words, his film was “sprung”. It had its television premiere on 4 September 1992 on PBS. In 2022, it was selected for inclusion in the US National Film Registry, films chosen as being “culturally, historically or aesthetically significant”.

HIGH SCHOOL

Wiseman’s second feature begins with what was a departure from his usual practice: not the establishing shots of downtown Philadephia, but the fact there is non-diegetic music on the soundtrack. This is Otis Redding’s US and UK number one hit single, “(Sittin’ on) The Dock of the Bay”, very current as it had been released in January 1968, two months before shooting began, which took place over five weeks from March to April. There’s another, subtler, use of non-diegetic music later in the film. As an English teacher talks about the Simon and Garfunkel song “The Dangling Conversation” (a 1966 single from their third album, Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme), concentrating on the lyrics and the poetic devices Paul Simon uses, to a largely bored reception, we hear the song itself, not from the tape player the teacher has but the original recording on the soundtrack. The lyrics of the Redding song talk of “wasting time” – is that a comment on what we are about to see?

High School, at an hour and a quarter one of Wiseman’s shortest, gives us a picture of another American institution, specifically Northeast High School in Philadelphia. There is a sense of a clash between the values of an older generation and those of a younger one, not yet part of a then-burgeoning counterculture but soon in many cases to be such. Certainly the activities of youth were worrying their parents’ generation and the education system did often attempt to control this. Girls have typing classes (on actual typewriters, naturally) and there are segregated sex-education talks. Wiseman, as ever, does not comment directly, but you sense his sympathies are with the youngsters, even though he’s clearly a liberal of their parents’ age, thirty-eight at time of shooting. Possibly wary after the experiences of Titicut Follies, High School was not originally shown in Philadelphia due to vague hints of lawsuits, though you have to wonder what specifically the school had to worry about. Again, the film was shot with a small crew, with Wiseman directing and sound recording and editing, Richard Leiterman as cinematographer with an assistant. The film uses more camera movement than would later be usual, with more zooms in to big closeups than Wiseman would later employ. In later films the camera is usually rock-solid (presumably on a tripod) while here it appears to be hand-held in places. As with Titicut Follies, Wiseman selects a setpiece on which to end, here the principal reading a letter from a former student now serving in Vietnam. “When you get a letter like this, to me it means that we are very successful at Northeast High School,” she says. Whether that’s a good thing or not is for you to decide.

High School was released on 13 November 1968 and in 1991 it was selected for preservation in the National Film Registry. Wiseman returned to the subject matter in 1994 in High School II at greater length (220 minutes), this time at New York’s Central Park East Secondary School.

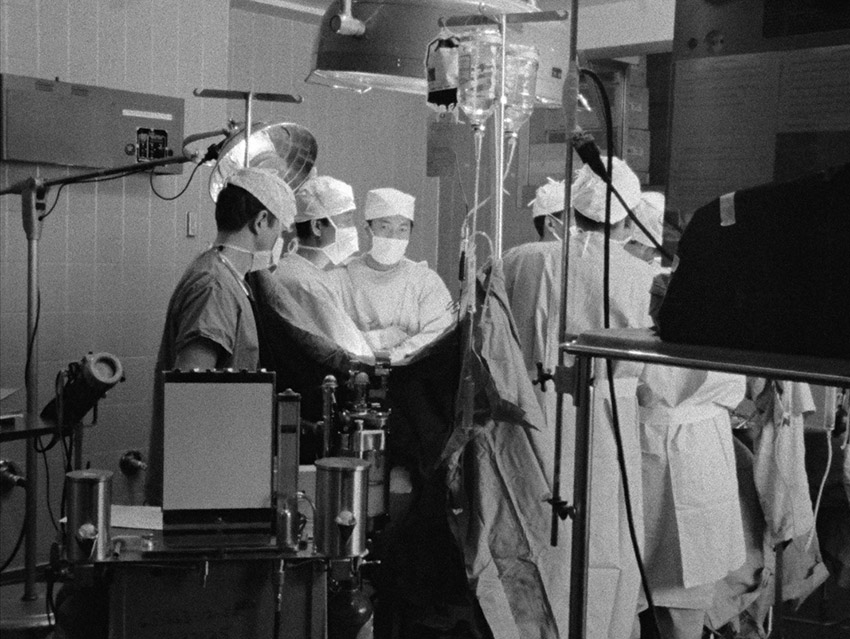

HOSPITAL

Hospital, released in 1970, was Wiseman’s fourth feature. This set omits his third, Law and Order, released the previous year. That tackled another American institution, namely the police force, filmed in Kansas City. With Hospital, Wiseman moved on to the medical industry for the first time, but not the last. We’re in the Metropolitan Hospital Center in New York City, With this film, Wiseman began a partnership with cinematographer William Brayne, who shot this and Wiseman’s next eight, including the two later films included in this Blu-ray set.

Wiseman spares us very little, as if to emphasise in the hour and a half due to him what the staff of the hospital are up against. So squeamish viewers should beware an opening sequence showing an incision made in a man’s chest in an emergency operating theatre. Emetophobes be aware that there is a quite lengthy scene involving a young student who has taken a drug, suspected to be mescaline, and is given a purgative, ipecac. It’s possibly merciful that his prolific vomiting was captured in black and white rather than colour. The film works as a succession of incidents – again without any commentary or to-camera interviews – depicting a system where an overworked staff have to deal with a constant stream of emergencies lesser or major, many of them involving the poor and/or marginalised, often relying on Medicaid for any treatment. The staff are compassionate but have to balance this with the workload. Among the patients we see are an old man who fears he has cancer, a transgender teenager and sex worker looking to obtain welfare, a young boy left alone with an ice cream and an old woman with a pulmonary embolism. Some of them, such as the student and a man who has been stabbed in the neck are fearful of their lives – they don’t want to die. Wiseman ends the film with a service in the hospital chapel, followed by a hymn.

JUVENILE COURT

We now move forward three years and skip over two more features. Basic Training (1971) took on the military. It was shot in the summer of 1970 at Fort Knox, Kentucky, and followed a group of young men – both enlisted and draftees – as they undergo infantry training, with an aim to turn them from civilians into a fighting force. Essene (1972) was distinctly different, the institution here being religious, namely a Benedictine monastery, with an emphasis on the brethren’s personal needs and how they are affected by those of the community as a whole. In between these two came a curiosity, I Miss Sonia Henie (1972). This was a portmanteau film, made in former Yugoslavia (Slovenia) lasting sixteen minutes, with an impressive list of eight directors including Tinto Brass, Miloš Forman, Buck Henry, Dušan Makavejev and Paul Morrissey as well as Wiseman. Each director’s contribution lasts only a few minutes and comprises static shots in the same bedroom set and at one point someone says the words of the title, invoking the Olympic champion Norwegian figure skater, who had passed away two years earlier. The directors’ contributions are intercut, so who shot what is hard to say, and it ends with the real Henie in an ice-skating sequence from the end of Sun Valley Serenade (1941), including that film’s end credits. This, incidentally, was Wiseman’s first work as a film director in colour (and 35mm).

Juvenile Court unusually doesn’t have a title card at the start, with the actual title appearing diegetically as a sign – “Juvenile Court 616”, to be precise. We’re in Memphis, Tennessee, in January and February 1972, and we see a variety of cases brought to the legal profession’s attention. Youngsters are looking to be placed in foster homes, have suffered sexual and physical abuse. Others have committed crimes, which include armed robbery and sexual offences. As well as the young defendants, we see at work lawyers, social workers, child psychiatrists and counsellors. There is one judge in this court, Kenneth A. Turner, who remained in post from 1963 to 2006. How much the system will help these young people is questionable.

Wiseman himself described the film in an interview as “a portrait of the dissolution of the American family”. Maybe so, and it’s certainly the case that the families we see and hear about here are distinctly dysfunctional. Edited from sixty-three hours of footage, Juvenile Court at just under two and a half hours was the first of Wiseman’s films to have an extended running time. This enabled more complexity – as before, with no narration or other commentary, we are left to judge for ourselves – and adds to the impression that this is another institution up against it in terms of workload, as one incident piles on another, with no real let-up for a longer period of time than many a similar documentary. We only go outside the court and its offices at the beginning and end of the film. The longer running times allow some scenes to play out at length, in Wiseman’s longest films for sometimes as long as ten or twenty minutes. Juvenile Court premiered on PBS on 1 October 1973.

WELFARE

This set ends just under a decade into Wiseman’s career as a documentarian, with Welfare. We have skipped one film between Juvenile Court and this: Primate (1974). In Yerkes Primate Research Center in Suwanee, Georgia, scientists study the development of the animals of the title, not just their abilities to learn but also the effects of drugs and alcohol on their behaviour and the control of their more aggressive and/or sexual side. Derek Malcolm in The Guardian described it as “about one set of primates who have power, using it against another who haven’t”.

Primate ran a more modest 105 minutes, but with Welfare, we are back to a more extended running time, just over two and three quarter hours. We’re in New York City at the Waverly Centre, in January and February 1974. and we see a large number of problems brought to the attention of the welfare system, including housing, unemployment, marital breakdowns, child victims and the elderly. A woman who has not received her welfare payments and is facing homelessness pleads with the authorities and it turns out her details have been misfiled. She’s not on the system, so she might as well not exist. She is one of many people we see in need of welfare of various kinds.

Again the emphasis is on a system where overworked people struggle to make a difference (or not). The lengthy running time risks becoming oppressive as Wiseman shows us incident after incident, often proceeding by means of juxtapositions rather than any chronological “narrative”. As ever, with no narration, captions or interviews, we are left to assess for ourselves. Similarly to Juvenile Court, we never leave the institution of the title after establishing shots at the start. Many of the people we see are referred from one office to another on different floors of the building. Not for nothing does one man at the end of the film cite Kafka. However, the film is not entirely grim, as there are moments of humour in between like diamonds glinting in the dirt. Wiseman’s humanism is always evident. Welfare premiered on WNET on 24 September 1975. The film has a political dimension, given that the dismantling of welfare was part of the campaign of future President Ronald Reagan, often using fraudulent claimants as a stick with which to beat the system.

sound and vision

Cinema Expanded: The Films of Frederick Wiseman is a three-disc box set released by the BFI, the three Blu-rays encoded for Region B only. In the order above, two films are on the first disc, two on the second, one on the third. While documentaries can be exempted from classification if they contain nothing which would receive more than a PG certificate, that isn’t the case here. The set has a 15 certificate, which is due to Titicut Follies, Hospital and Juvenile Court, while the other two films are rated 12. The BFI has provided advisories in front for three of the films, due to “child sexual abuse references, disturbing images” (Titicut Follies), “strong injury detail, upsetting scenes, medical detail” (Hospital) and “references to child sex abuse, references to self-harm” (Juvenile Court). The transfers of Hospital and Juvenile Court end with restoration credits, with prominent thanks given to Steven Spielberg.

All five films were shot in black and white 16mm, and the Blu-ray transfers are based on 4K scans and remasters from the original negatives (supervised by Wiseman) for all but Titicut Follies, which was supplied to the BFI from a 4K scan and remaster by Wiseman’s company Zipporah Films. They are in the ratios of 1.37:1 (Titicut Follies, Welfare) or 1.33:1 (the other three), as befit 16mm-shot documentaries whose primary outlet, other than festivals and 16mm non-theatrical distribution, was on television, which at the time was 4:3. Given the 16mm origins and the shooting in available light, some shots are a little soft and grain is always evident, though pullings of focus are down to the original filming. For technical reasons, I have been unable to take screengrabs from the discs, so this review is illustrated by stills provided by the BFI.

The soundtrack is the original mono in all cases, rendered as DTS-HD MA 1.0. Given that the soundtracks are almost all directly-recorded, it’s notable that dialogue is clear, as are what would be called sound effects in a fictional film. The music, all diegetic except for the examples in High School mentioned above, is on point too. English subtitles for the hard of hearing are available for all the features and are almost entirely accurate. One quibble, though: in Hospital and Juvenile Court, women are addressed as “Miss” but the subtitles render this rather anachronistically as “Ms”.

special features

2025 BFI Southbank discussion (21:41)

Included on Disc One, this discussion took place at the BFI Southbank in London on 13 November 2025 following a showing of High School. I attended, though as there are no shots of the audience, you can’t see me. Sandra Hebron, curator of the venue’s Wiseman retrospective, moderates the discussion which features artist and filmmaker Andrea Luka Zimmerman and curator and researcher Matthew Barrington to discuss Wiseman’s work. For Zimmerman, watching Titicut Follies was a formative experience for their work and they talk about how Wiseman’s film give his subjects dignity, citing a scene in that film. Barrington sees Wiseman’s work as featuring an openness, it being a process of discovery for him as much as for the audience. Hebron leads a discussion from a Wiseman interview quote, that “indirectly all my films are political”, with Barrington mentioning the civil unrest and Vietnam War protests taking place outside the venue as High School was filmed. At the beginning Hebron says that the event has been allocated thirty minutes, which at the end she apologises they have overrun, but as you can see from the running time, this has been shortened somewhat. There’s only one question from the audience (represented by a caption). We don’t hear a question from the audience by John Davey, Wiseman’s cinematographer on more than thirty films.

Corridors of Power, Windows to the Soul (11:16)

On Disc Three, this is a video essay put together and narrated by Ian Mantgani, and is subtitled An Introduction to the Films of Frederick Wiseman. Many of the basic points are covered, with Mantgani preferring Wiseman’s coverage of institutions to be thought of as investigations of “ecosystems” and tapestries weaved about society. He discusses some of Wiseman’s filmmaking strategies, such as placement of objects in frame and of people in corridors and pathways creating hierarchies. But the interactions we see are sometimes examples of bullying (be advised of a disturbing scene from Titicut Follies) they are sometimes ones showing cooperation and supportiveness, such as a scene from Multi-Handicapped (1986) showing a sensorally-impaired child being helped to negotiate a walk down a corridor. But ultimately the films make us active viewers. Mantgani ends by saying, “I find myself people-watching and thinking of the structure of life differently”, and maybe they will have that effect on others watching. As well as the scene from Titicut Follies mentioned above, be also advised that this essay includes some of the vomiting scene from Hospital. There are clips from a variety of Wiseman’s films, not just the five in this set but eight others, not all identified on screen but listed in the end credits.

Book

The BFI’s perfect-bound book with the first pressing of this release runs to fifty-two pages plus covers. It begins with “Deep Cuts – Frederick Wiseman’s Early Years” by David Jenkins. This is an overview of Wiseman’s career, though concentrating on the five films in the set, and the essay title has a double meaning. Jenkins begins with a comment about the role of editing in Wiseman’s films (often taking up to a year, much longer than the actual shooting time) and starts with “In film, we take the humble cut for granted” before pointing out that Wiseman does no such thing and cuts are a vital part of his method. Such a method was in place from the outset, as we move in Titicut Follies from the revue which gives the film its title to some of the same inmates in the conditions they have to live in. Jenkins says that Wiseman’s films are not muckraking, campaigning exposés of their subject matter but are undertaken more in an anthropological sense, though as stated above any objectivity is an illusion. He calls his own films “non-fiction fictions”. The inmates’ naked bodies are often seen in Titicut Follies, and Wiseman in his later career has shown an interest in the ways the human body is on display, including in the fashion industry (Model, 1981) or in dance (Ballet, 1995, and La danse: Le ballet de l’Opéra de Paris, 2009) or in the ways that its function is impaired (the four films made in 1986 at the Alabama School for the Deaf and Blind, Blind, Deaf, Adjustment & Work and Multi-Handicapped).

This is followed by essays on each of the five films: Arlin Golden on Titicut Follies, Stephen Mamber on High School, Shawn Glinis on Hospital, Eric Marsh on Juvenile Court and Philip Concannon on Welfare. These expand upon the points made in the overview and in some cases fill in details that we don’t learn from the films themselves, for example the career of Judge Turner in Juvenile Court, particularly accusations that some of his decisions were racist, not something that features overtly on screen.

Next up is a lengthy archival piece, “American Institutions” by Thomas R. Atkins, reprinted from the Autumn 1974 issue of Sight & Sound. This begins with discussing the opening of Juvenile Court, at the time the most recent of Wiseman’s films, and how such an opening is typical of Wiseman’s ways to immerse us in his subjects. As the title suggests, Atkins points out that the films are portraits of particular institutions (then, entirely in the USA) and the filmmaking process was as much a voyage of discovery for Wiseman and his small crew as it would be later for the audience – in this case, reducing 125,000 feet of 16mm film to 144 minutes of running time. Wiseman’s films do not focus on individuals (Atkins’s examples of films which do are the Maysles Brothers’ Salesman and the twelve-part PBS series An American Family (1973)), but feature a wide variety of people, male and female (and sometimes transgender), of various ethnic origins and all ages. Atkins talks about Wiseman’s earlier films, including two of the three not in this set (Law and Order and Basic Training). The article ends with a look forward to what would be Wiseman’s next film, Primate, but what Atkins says could apply to any of Wiseman’s films, that it “will not be an easy experience but another hard ‘voyage of discovery’ by the artist who has become, in seven years, one of America’s leading filmmakers.” There are a few edits in this reprint from the original publication, such as an update to note that the ban on Titicut Follies was lifted in 1991.

The book concludes with notes on the two on-disc extras and on the transfers. There are also plenty of stills, though no credits for the films themselves, however minimal they would have been.

final thoughts

Given his large filmography, this set is inevitably a sampling of Wiseman’s work, concentrating on his first decade, based on digital restorations of his film-shot work that he has carried out in recent years. The set is in conjunction with a larger sampling making up a three-month retrospective at the BFI Southbank, nine films (including three on this set) available on BFI Player simultaneously with this box-set release, and the cinema release of Menus-Plaisirs: Les Troisgros. It doesn’t say “Volume One”, but let’s hope there are more to come.

Cinema Expanded: The Films of Frederick Wiseman

Titicut Follies

US 1967 | 84 mins

directed by: Frederick Wiseman

Juvenile Court

US 1973 | 144 mins

directed by: Frederick Wiseman

High School

US 1968 | 75 mins

directed by: Frederick Wiseman

Welfare

US 1975 | 167 mins

directed by: Frederick Wiseman

Hospital

US 1970 | 85 mins

directed by: Frederick Wiseman