The Wild Child [L’enfant sauvage]

François Truffaut’s THE WILD CHILD (L’ENFANT SAUVAGE), telling the true story of the Wild Boy of Aveyron, is released on Blu-ray by Radiance. Review by Gary Couzens.

In 1798 in Aveyron, France, a young boy (Jean-Pierre Cargol), somewhere between ten and twelve in age, is found in the woods naked, filthy, unable to speak and living a scavenger’s existence. On the assumption that the boy is deaf-mute, he is sent to an institution in Paris. His case comes to the attention of Dr Jean Itard (François Truffaut). When he reacts to the name Victor, the boy is given that name. Itard takes upon himself the task of “taming” Victor and teaching him to read and hopefully speak.

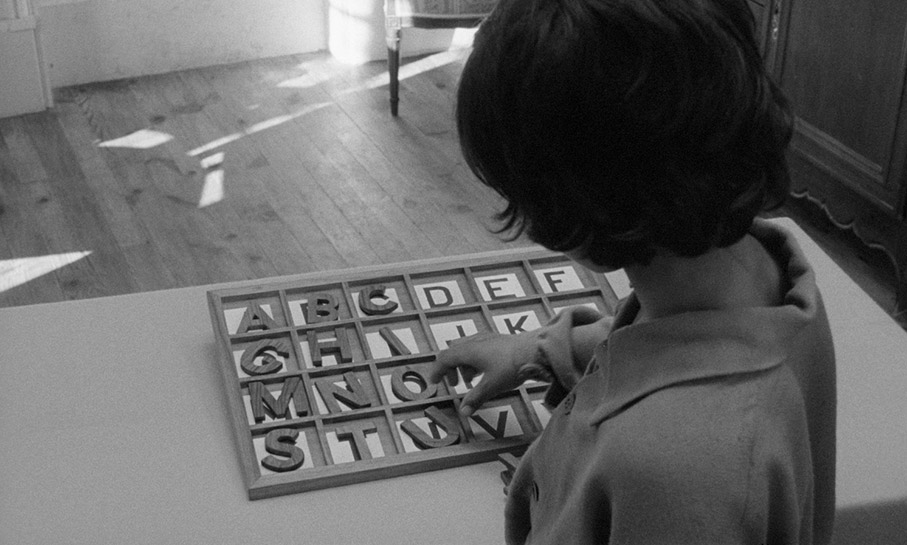

Truffaut always had an affinity with children and childhood, which informs some of his best films. (All about boys rather than girls, though.) The Wild Child is one of those. Based on the true story of the Wild Boy of Aveyron (c. 1788-1828), cowritten by Truffaut and Jean Gruault from Itard’s account Mémoire et rapport sur Victor de l’Aveyron, Truffaut’s film is clear-eyed about its subject. Learning and civilisation is an uphill struggle for Victor and there is no “cure”. There is still a long way to go when the film ends. The Wild Child is a story told simply and with great economy. Before and afterwards, Truffaut made uncredited cameos in his own films, but this was the first time he gave himself the leading role. He gives a self-effacing performance, giving centre stage to the extraordinary Jean-Pierre Cargol as Victor. Twelve years old when he made this film (he only made one more, Caravan to Vaccarès in 1974), it’s more remarkable as a performance done almost entirely through body language. He only says one coherent word – “lait” (“milk”), twice – in the entire film.

The film was shot in July and August 1969. Ten years earlier, Truffaut’s first feature film The Four Hundred Blows (Les quatre cents coups) had been released. That had been informed by Truffaut’s own troubled childhood, as embodied in the film by his alter ego Antoine Doinel, played by Jean-Pierre Léaud. So the story of The Wild Child, which Truffaut had wanted to make for some years before he did, likely held resonances for him. The film is dedicated to Léaud and there’s another echo in the final shot of the film, in which the child looks to camera, as Doinel did at the end of the earlier film, though not this time without a freeze-frame. Truffaut, who by this time had been a father for a decade, felt that The Wild Child was a significant film in his progress. Before, he had identified with the child, but here he did with the adult he cast himself as, a surrogate father. While Truffaut, like his devotee Steven Spielberg, could certainly be sentimental about children if he put his mind to it, he avoids it here. The film is quite austere in style, and not just because it’s in black and white. Itard’s diary, which we hear in the film as a voiceover, didn’t actually exist, but was added by Truffaut and Gruault to give Itard more of a voice in the film. The film makes sparing use of Vivaldi’s Concerto in C Minor, with its mandolin featuring heavily.

The Wild Child also began a significant creative collaboration for Truffaut. It was the first of his films to be shot by the Spanish cinematographer Nestor Almendros. They made ten feature films together, all but three of the ones Truffaut made after this. This was the longest partnership of Almendros’s career, only rivalled by his one with Eric Rohmer (seven features, three documentary shorts). Truffaut had been impressed by Almendros’s work on Rohmer’s My Night at Maud’s (Ma nuit chez Maud, 1969) and had assumed he was widely experienced with black and white. However, Maud was the first film Almendros, a year and a half older than Truffaut, had shot in 35mm black and white and only his fourth fiction feature of any kind. Almendros was delighted to be approached, as he was an admirer of Truffaut’s films up to that point.

Truffaut and Almendros deliberately harked back to the style of early cinema in this film, not only by shooting in black and white but also using some of the techniques of the silent film, especially irises to open or close scenes. Indeed, the film begins with an iris-out and ends with an iris-in. Almendros’s assistant had located a genuine old iris, which was used on the film. Almendros’s principle throughout his career was to favour natural light, or at least light that could be justified. The Wild Child takes place in an age before electricity, so the only light in interiors was via candles or through windows. None of the film was shot in the studio, and the houses, in the Riom region of France, were genuine period mansions which had been restored. Day-for-night scenes were shot with a red filter.

Black and white had become commercially obsolete in the later 1960s, in Western commercial cinema at least, and Truffaut, even though his films played in arthouses in the UK and USA due to being in French, was a commercially-intended filmmaker. It was this that had caused him in the late Sixties to make two films from novels by Cornell Woolrich under his William Irish pseudonym, The Bride Wore Black (La mariée était en noir, 1968) and Mississippi Mermaid (La sirène du Mississipi [sic], 1969), and in between them had run for cover by returning to Antoine Doinel with Stolen Kisses (Baisers volés, 1968). Mississippi Mermaid, with two big stars and shooting in foreign locations in colour and Scope, was a relatively expensive film aiming to replenish the coffers of Truffaut’s production company. The Wild Child, being a small, low-key, historical and more personal project in black and white, on a much lower budget, was not expected to be much of a commercial proposition. But relatively it was, and Mississippi Mermaid was not. Truffaut returned to black and white one more time with his final film Vivement dimanche! (Finally, Sunday! in the UK, Confidentially Yours in the USA, 1983), which was also shot by Almendros.

The Wild Child was released on 26 February 1970 in France. In the USA, it won the National Society of Film Critics Award for Best Cinematography, which Almendros shared with his own work on My Night at Maud’s. In the UK, it was shown at the London Film Festival on 18 November 1970 and went on release on 18 December, its main London venue being the Curzon Cinema in Mayfair.

sound and vision

The Wild Child is released on Blu-ray by Radiance, in a disc encoded for Region B only. The film had a U certificate in British cinemas and retains that on disc.

The film was shot in black and white 35mm (Kodak Double-X, Plus-X and Tri-X, for the cinematography buffs out there) and the Blu-ray transfer is in the intended ratio of 1.66:1, which was favoured by Truffaut for most of his career. (Certainly, all his features of his shot by Nestor Almendros are in that ratio.) Blacks are solid, whites on point, and the contrast and greyscale look as they should.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. There’s not much to report, with dialogue, sound effects and the Vivaldi music present and correct. English subtitles are optionally available and on by default, on the feature and the two French-speaking extras.

special features

On-set interview with François Truffaut (3:43)

This was broadcast on French television in January 1970 (and is in colour), when The Wild Child was awaiting its commercial release. As a voiceover states, this took place during the filming in July/August 1969 and at the same time Truffaut was writing the script of what would be his next film, Bed and Board (Domicile conjugal, 1970), the next in the Antoine Doinel series. In between behind-the-scenes footage, Truffaut speaks to camera. He didn’t want to make a film like The Jungle Book or Tarzan, but the priority was to make a film “real”, in other ways than as a documentary. It’s a poetic recreation of the true story, not a scientific one, and if Jean-Pierre Cargol makes a mistake, that makes him human rather than animalistic.

Interview with François Truffaut and Lucien Malson (9:49)

From the French television programme L’invité du dimanche in October 1969, and in black and white, this is a double-headed interview. At the time, The Wild Child was in the process of being edited. Truffaut talks about how his first encounter with the story of Victor of Aveyron was a book on feral children by Lucien Malson, which also reprinted Jean Itard’s account. Malson is on hand to talk about this, and the subject of feral children in general. Truffaut says that his film emphasises some conceptual breakthroughs for Victor: his first time wearing shoes, first time riding in a carriage, and so on. He also thought it best not to use professional actors, which led to his casting himself as Itard.

Appreciation by Ginette Vincendeau (18:51)

Newly recorded for this release, French cinema expert Vincendeau talks about The Wild Child. She talks about how the film reflects Truffaut’s own childhood but also describes his two mentors, not just the famous one, André Bazin as a critic but also the educator Fernand Deligny, who also became a film director. Vincendeau also discusses the circumstances of the film’s making, and the way that this modest film not considered likely to be a big financial success actually did better than the glossy star vehicle Mississippi Mermaid which had preceded it. She also talks to the film’s mise-en-scène, in particular the use of windows and people looking out of them, counterpointing civilisation with the wilderness from which Victor came.

Theatrical trailer (1:30)

Another Truffaut film, another American trailer which uses a voiceover narration and has no spoken dialogue, lest the presence of subtitles put potential patrons off. The black and white was obviously unavoidable, though. “Look at him – proof of the animal in all of us,” says Voiceover Man over a close-up of Victor.

Booklet

The booklet with this limited edition contains archival writing by Truffaut and Almendros (presumably the relevant section of his book A Man with a Camera, my copy of which I consulted for this review) and new writing by Adam Scovell. It was not available for review. Once the limited edition sells out, a future standard edition will not include the booklet.

final thoughts

The Wild Child is a modest film which turned out to be one of Truffaut’s best, kicking off the last and rather uneven full decade of his career. Again, I have no complaints about its presentation on Blu-ray by Radiance.