New York times

When his daughter is mistakenly targeted by a kidnapper looking to punish a greedy property developer, her father risks life and limb to locate and rescue her in the criminally underseen 1980 crime thriller NIGHT OF THE JUGGLER. Slarek is transported back to a golden age for American genre cinema on Radiance’s first release under the new Transmission label.

“This film doesn’t OPEN with a chase sequence. This film IS a chase sequence.”

Novelist and critic Kim Newman on Night of the Juggler

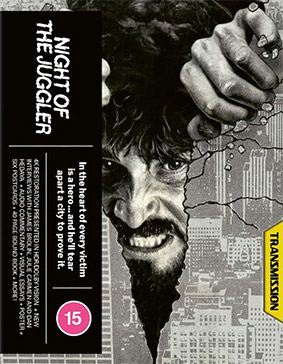

If you were as new to the title Night of the Juggler as I was when it was first announced for a UHD and Blu-ray release by Radiance on the new Transmission label, what sort of film did those four words conjure up in your mind, especially considering that it was made in America at the very tail end of the 1970s? Thanks in no small part to a certain late 60s genre-changing masterpiece from director George Romero, that decade and the one that followed were awash with horror titles that took place on a whole range of nights, of the damned, the devils, the sorcerers, the lepus, the skull, the blood monster, the comet, the creeps, the werewolf, the howling beast, and doubtless many more. Of course, jugglers don’t have quite the same scary rep as clowns (itself a fear I’ve personally never understood), but that’s never stopped horror filmmakers from picking titles are based around characters that would only really come across as threatening within the confines of the film in question. Try The Nanny (Seth Holt, 1965), The Gardener (James H. Kay, 1974), The Child (Robert Voskanian, 1977), The Sender (Roger Christian, 1982), The Hitcher (Robert Harmon, 1986), The Carpenter (David Wellington, 1988), or even Alfred Hitchock’s The Birds (1963). And consider that in William P. McGivern’s source novel the antagonist of the title was so nicknamed due to his habit of cutting the jugular vein of his victims and you’ve surely got the basis for one of the first slasher movies of the 1980s. And come on, look at the image on the slip cover of this UHD release, which features a face of what looks like a crazed killer peering menacingly through a hole that we can assume he has busted through a wall to get at a terrified victim who was hiding in a room in which she or he mistakenly thought they were safe.

Now I may just be letting my imagination run away with me a little there, but this perception is seemingly confirmed by the film’s quietly arresting opening scene, in which a man – who we later learn is named Gus Soltic (Cliff Gorman) – is seated at a café table dressed in a Department of Works uniform, listening to music and gazing at a folded-up newspaper page, his face the very picture of a someone with anger and possibly even psychological issues. When the fried breakfast he ordered is placed in front of him, he sourly rearranges its contents to form the effigy of a human face, then pours blood-red tomato sauce into its fried egg eyeballs and sharply departs without eating a thing. This, we can presume, is our jugular-slashing killer, and he clearly intends to take out whatever frustration is seriously bugging him on some as-yet unspecified and unaware innocent party.

Before we find out who that individual might be, we’re introduced to a couple of initially unrelated characters who will play a significant part in the drama that is soon to unfold. The first is rotund and world-weary police Lieutenant Tonelli (Richard Castellano) as he rolls up at a government building where a bomb has been planted by a group calling itself the Puerto Rican Liberation Army. As the cynical coordinating sergeant reads the group’s written declaration to Tonelli, the detective irately dismisses it in a manner that suggests that this is far from the first such incident he’s handled. Tonelli responds to the sergeant’s question about what he wants to do by requesting a coffee, a Danish and three aspirin. “Make it six,” replies the sergeant, to which Tonelli responds wearily, “I got a feeling it’s gonna be another goddamn New York day.”

It’s then that we meet our leading man in the shape of upbeat truck driver Sean Boyd (James Brolin), as he finishes his night shift and arrives at the dispatch office in time to see the two female office workers battling to dispose of a rat that Sean casually executes when it foolishly sticks its head between the base and the blade of a guillotine paper cutter. He then collects his wages and takes a cab home, stopping off on the way to buy a couple of hot dogs from chatty street food vendor.

When we next encounter Gus, he makes a call from a public phone box to the Clayton household, whose social status is inferred by the fact that the phone is answered by family maid Edie (Joanna Featherstone). Gus claims to be from the Ashley School and conducting an attendance check and is calling to confirm that the family’s teenage daughter Virginia (Robyn Finn) will be at school today. Oh dear Lord, is Gus targeting children? Just how dark is this film going to get?

We then rejoin Sean as he arrives home and delivers a birthday hotdog to his cheerful 13-year-old daughter, Kathy (newcomer Abby Bluestone). There’s real chemistry here between the actors and characters, which makes the bond between them as instantly easy to believe as the one between Chris MacNeil and her daughter Regan in the early scenes of The Exorcist (1973). In the conversation that follows it becomes clear that Sean and his wife Barbara (Linda Miller) are separated and that Kathy is being pressured by Barbara to move in with her in Connecticut, something Kathy has no real interest in doing.

As Gus make a series of unclear preparations, steals a car, and checks that Virginia has left home and is walking alone to school, Sean jogs lightly alongside Kathy as she heads to the same place of learning, only to be sent home to get some sleep by his confident daughter when his tiredness gets the better of him. Gus, meanwhile, has positioned himself on the route that Virginia takes to school with the aim of kidnapping her. It’s soon revealed that her father, one Hampton Richmond Clayton III (Marco St. John) if you please, is a property developer who has become rich by buying land at bottom dollar prices for development on which recently condemned housing units once stood, including many that were once owned by Gus’s family. The angry and embittered Gus plans to balance – or as the film would have it to justify the title, juggle – the books by holding Virginia hostage and demanding a million-dollar ransom for her safe return. There’s just one thing. Unbeknown to either party, Kathy is a dead ringer for Virginia, and that day is even dressed in the exact same clothing and is ahead of Virginia on the walk to school. As a result, when she approaches the location at which Gus is waiting, he mistakes her for Virginia and kidnaps her instead.

If this setup sounds at all familiar then it’s probably because you’ve either seen Kurosawa Akira’s 1963 High and Low [Tengoku to jigoku] or read Ed McBain’s King’s Ransom, the novel on which that film was based. In both, a ransom is demanded of a wealthy businessman for the safe return of his kidnapped son, but the kidnappers have unknowingly grabbed the son of the businessman’s chauffeur by mistake. That, it should be noted, is where the comparisons between Night of the Juggler and those earlier works end, as while the primary focus of both King’s Ransom and High and Low is the businessman and the question of whether he will pay a hefty ransom to save another man’s the child, here the story revolves around the kidnapper, his victim, and the victim’s father’s relentless pursuit of the man who has taken his daughter. And when I say relentless, I’m not being remotely hyperbolic. When Gus brazenly grabs the startled Kathy from a crowded New York street and carries her protesting to his car, she and Sean have only parted company a couple of minutes earlier, and Sean hears and sees the kerfuffle from a distance, realises what is happening and immediately gives chase. What follows plays unashamedly like an all-out attempt to top the brilliant centrepiece car/train chase sequence in William Friedkin’s The French Connection (1971), and while that’s a tall order for even the most talented of filmmakers, what unfolds here comes impressively close and even wins out in its length and the sheer variety of its content. Running for a superbly executed 11 pause-free and breathless minutes, the pursuit here begins with what initially seems a hopeless imbalance, as Gus drives away at speed with Sean belting after him on foot. As New York traffic jams bring Gus to a halt, however, the desperate Sean enlists the aid of overexcited Puerto Rican taxi driver Allesandro (Mandy Patinkin) and is soon hot on the frantic Gus’s tail. What follows involves more traffic jams, blocked roads, driving at high speed along pavements, minor prangs and destructive crashes, a dash into the subway and pursuit through the moving train, Sean physically assaulting a police officer who gets in his way, a tumbling collision with a bag lady’s trolley, a stolen telephone repair van, the hijack of a street preacher’s vehicle with the frightened owner on board, a determined attempt by Sean to ram Gus’s vehicle off the road, and a whole lot more. It’s a blistering sequence that sets the tone for the story to follow, which while never hitting the same pace again, the film continues to move at a considerable lick, with only short pauses for character-based scenes that always advance the plot in some way.

Crucially, at no point does Gus realise that he has kidnapped the wrong girl, and as he and Kathy make their way to his now slumland apartment, Kathy’s insistence that she is not Virginia, and her father does not have the funds to pay any kind of ransom falls on dismissively deaf ears. There is thus some confusion at the Clayton residence when Gus phones to demands that they pay him a million dollars if they ever want to see their daughter again, unaware that by this point she is safely back at home. The Claytons contact the police, and who should be assigned to the case but Lieutenant Tonelli, whose professional handling of the situation is matched by his contempt for Clayton and his miserable money-grabbing ilk. Things meanwhile complicate further for Sean when he’s taken to be booked at a police station at which a plain clothes detective named Sergeant Barnes (Dan Hedaya) is currently stationed. It’s here that we learn that before finding work as a trucker Sean was a police detective who turned whistleblower on his corrupt colleagues, one of whom was the crooked and adulterous Barnes. This led directly to the collapse of Barnes’s marriage and destroyed any promotional hopes that he had once he was eventually reinstated. It’s also intimated that the resulting bad feeling this generated was the prime reason that Sean was also later canned. Barnes has clearly been harbouring a mother of a grudge against Sean ever since, one that resurfaces the very moment he lays eyes on him again and that he acts on by taking Sean to an interrogation room and beating seven bells of shit out of him. When Sean eventually and inevitably hits back and knocks Barnes unconscious, he uses the opportunity to escape and continue his independent quest to locate his daughter, but now not only has the police on his back, but Barnes quite literally gunning for him too. Eventually, a dropped clue leads him to a dog pound where he is given crucial information by young Latina employee Maria (Julie Carmen), who sympathises with his predicament and ends up tagging along and assisting him any way that she can.

Although released in 1980, Night of the Juggler is very much a product of American 70s cinema and bears many of the hallmarks that made the decade such a great period for American crime and thriller movies. Real cars barrel down genuine New York streets and have authentic collisions, while actors run, dodge, fall and even shoot on real city locations and interact with non-professionals and even unaware passers-by. People are cast because they are an authentic fit for the people they are playing rather than because of their good looks or their box office mojo, something especially true of the supporting players, many of whom are New York natives and are each given a memorable trait or an interesting bit of business to ensure that they all register. As a result, every character in the film looks, sounds and feels like the real deal, which in some cases they are, with even leading man James Brolin burying his rugged looks beneath the beard and shoulder-length hair of many a real trucker of the day. The action, the characters and the locations all have a genuinely tactile feel, a quality that even the most well-crafted and well-intentioned modern urban Hollywood thriller would struggle to recreate, reliant as it would be on CGI assistance to fake an authenticity that this film has in droves. There’s also considerably more nuance to the character of Gus Soltic than there would be in the one-dimensional Hollywood antagonists that predominated in the decade that followed. That his anger at the way he perceives life has treated him is expressed through anger and bigotry has a disturbingly contemporary ring, yet while Kathy initially has good reason to fear and even attempt to flee him, there are moments when the humanity we can assume he once had still flickers to the surface and prompts an almost sympathetic response from his young prisoner. Later, this takes the film into territory into which a modern Hollywood production would be understandably reluctant to tread, as Gus develops a seemingly fatherly fondness for Kathy, which at one point takes a turn that I can almost guarantee would be nixed at the script stage in a studio film today.

Inevitably, given when the film was made, there are aspects that have not dated as comfortably as others, and while they do accurately capture attitudes and language of the day, the fact that these views are once again being expressed by the dispossessed in increasing numbers can’t help but make these scenes an uncomfortable watch. Central to this is Gus himself, who may indeed have good cause to have a grudge against land-grabbing developers like Clayton, but whose anger is equally targeted at ethnic minorities in his anger-spitting use of offensively derogatory terms for blacks and Latinos and claims that they’ve been sent in by the rich to wreck the estate and burn it to the ground. While it seems clear that we’re not meant to sympathise with Gus’s prejudicial rants, the film itself than walks into equally dodgy territory by presenting the first significant black character as a middle-aged alcoholic paedophile, then having the TV repair van that was stolen and abandoned by Gus descended on and stripped bare in seconds by a gang of young black men who carry out the task with almost euphoric glee. Later in the story, Sean is targeted, threatened and chased by a Puerto Rican gang when his investigation takes him into what Maria warns him a bad neighbourhood, in part because the gang takes offence at the idea that this white guy is hanging out with a girl that they regard as one of their own. It is, however, worth remembering that this film was made and set in what was the grimmest period in late twentieth century New York history, when corruption and deprivation were widespread, public service strikes were common, crime and gang violence was on the rise, and the Police Union was handing out an alarmist pamphlet titled Welcome to Fear City: A Survival Guide to Visitors to the City of New York to incoming tourists, which was peppered with tips to help keep yourself safe from a range of perceived threats during your stay. Some balance is also provided by characters that kick against what these borderline social and racial stereotypes, from the sympathetic Maria to the wildly eager Puerto Rican cab driver who comes to Sean’s aid and rants about how most perverts seem to be white guys. Later, following a confrontation with the Puerto Rican gang, Sean is driven to safety in the nick of time by black female cabbie Candy (Saundra McClain), who lectures him as she drives on why the gang would target some unidentified white man who comes into their neighbourhood and starts asking questions, and points out how little his kind have learned about the racial divide they have effectively created.

Although Robert Butler is the sole credited director, it’s now known that the film was begun by The Ipcress File, The Boys in Company C. and The Entity director Sidney J. Furie, who left the production due to a disagreement with the producers after Brolin fell and broke bones in his ankle during the opening chase sequence. As is made clear in the special features, however, it’s Furie who effectively set the style of the film, one that Butler wisely chose to follow and would later repurpose for the pilot episode of the hugely influential police drama series Hill Street Blues. It doubtless helps that acclaimed New York born cinematographer Victor J. Kemper (Husbands, The Friends of Eddie Coyle, Dog Day Afternoon, Stay Hungry, Coma, and so many more of note) was fully on board with Furie’s long lens approach by the time Butler came on board, providing a bridge between these two very different directors that ensures the join between the Furie and Butler helmed material remains invisible.

As noted above, the casting is spot on in the matching of actors to their characters, and the resulting performances are excellent across the board. Despite some strong competition, this may well be my favourite performance by James Brolin, who is equally convincing as a caring father (his almost fatherly ease with young first timer Abby Bluestone, who only has three film credits, really helps) and as the furiously determined ex-cop who will stop at nothing to rescue his daughter. And while this and his past life as a Serpico-like exposer of police corruption may seem to paint him as a clean-cut hero, a single interaction with his ex-wife Barbara, one that leaves her in a flood of tears, suggests that there’s a selfish and perhaps more brutish side to his personality, one that at the very least contributed to their acrimonious breakup. As the seriously troubled Gus, Cliff Gorman captures the essence of a man whose anger at the downfall of the city in which his family once held sway and frustration at the cards that life has dealt him has become twisted by bigotry (you can’t help wondering just what sort of landlord he must once have been) into a sort of psychotic desperation. Underlying this, however, is a degree of clear thinking that makes it seem likely that, had the kidnap been executed as originally planned, he might well have got away with it and spent the rest of his life in comfortable seclusion. Few actors could of his day could seem as wild-eyed and power-keg dangerous as Dan Hedaya, characteristics that are on full display here in his fury at meeting up again with Sean and the reckless abandonment of his subsequent pursuit. And while Richard Castellano will forever remain best known for his portrayal of Clemenza in The Godfather (1972), I can’t help wishing that he’d got to play the cynically world-weary Lieutenant Tonelli in a couple more films.

Having now watched and thoroughly enjoyed Night of the Juggler three times (plus once more for the commentary) and having grown up on that treasure trove of great movies that defined American cinema in the 1970s, the fact that I’d previously never even previously heard of this film continues to mystify me. It scores both as a crime thriller and a vivid time capsule record of city that feels on the brink of social collapse, even if this means being made to feel uncomfortable by some its elements. There are small holes to pick if you are so inclined (it’s hard to believe that Kathy would not be more vocal in her protests and call out for help when first grabbed by Gus, and the speed with which Sean recovers from an injury that initially needs a walking aid seems almost miraculous), but for my money Radiance has uncovered a nugget of unfairly buried treasure for the first Transmission release, one that should be sought out with gusto by any fan of reality-based 1970s American thrillers.

sound and vision

Night of the Juggler was made during a period for American cinema when a preference for shooting on location required the use of faster film stock, and the resulting aesthetic had more in common with documentary filmmaking than the pristine sheen of Hollywood productions of decades past. Nostalgia plays its part here, as I saw many of the films from this era on the big screen either on their initial release or later double-bill reruns, and it’s thus a look I have a particular affection for, one that is handsomely captured by the restoration and transfer here. Although there is some small variance due to the manner in which the film was shot (long lenses have a flattening effect and a narrower depth of field, and you only need to be a few centimetres off for the image to soften just a whisper), the sharpness of the best material is impressive and the detail clearly defined. The contrast is very nicely graded throughout, nailing the black levels without feeling aggressive, and the colour is largely naturalistic, with accurate-looking skin tones. The film grain is clearly visible throughout and I wouldn’t have it any other way, and the image is free of blemishes and stable within the frame. I should note that I’m referring to the UHD here, where Dolby Vision HDR seems to have given the image a brightness boost, as while the Blu-ray transfer uses the same restoration, the image is noticeably darker than the more vibrant one on the UHD, resulting in considerably less shadow detail and a slightly glummer feel to the film overall. In other respects it’s a strong HD presentation, but the UHD is superior on just about every front.

The mono soundtrack is presented as a Linear PCM 1.0 track on both discs and is damage free, with clear reproduction of dialogue, music and effects, and a decent tonal range for a mono soundtrack of this era. Once again, however, the UHD has a noticeable edge, with a slightly brighter feel to the soundtrack overall.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are included on both discs.

special features

Audio Commentary by Kim Newman and Sean Hogan

I’ll freely admit that my heart lifts every time I see that novelist and critic Kim Newman is involved in a commentary track, as for me this is a guarantee that it will be an arresting and educational blend of facts and opinion and a hugely enjoyable listen from start to finish. Here he is teamed with film historian and filmmaker Sean Hogan, and the two have recorded enough commentaries together by this point to bounce entertainingly off of each other, ensuring that there are only a few short pauses for breath, and that most listeners (myself included) will come away knowing way more about the film and those involved in its making than they did when they went in. As ever with commentaries as astute as those by Newman and Hogan, many of the things I had observed and noted down to include in my review are brought up here and covered in enough detail to make it look as if I’d cribbed heavily from them (I even dropped a couple, partly as a result). These include the similarity to the plot of Kurosawa’s High and Low and the Ed McBain novel on which it was based, the proto-Joker nature of Cliff Gorman’s character, the wandering into The Warriors and The Wanderers (both 1979) gangland territory, and the troubling but still prescient nature of the film’s social and racial politics. They provide some useful detail on many of the supporting characters, several of which are played by actors who later had notable film careers, praise the opening chase sequence as “incredible,” and discuss the social situation in New York and particularly The Bronx in the late 1970s and how this was reflected in the cinema of the day. Usefully, both have read William P. McGivern’s source novel and outline some of the changes made for the film. They also recall the impact of police drama series Hill Street Blues, early episodes of which were helmed by director Robert Butler, and note that despite the change of director here, there is no loss of continuity in the film’s style and pacing.

Summer of ’78: Interview with James Brolin (13:50)

By my calculation, actor James Brolin was in in his mid-80s when this new interview was conducted, but you absolutely wouldn’t know it from the cheerful energy and liveliness of his responses. He discusses his relationship with director Sidney J. Furie, recalling that he had the best time on Furie’s previous biopic Gable and Lombard (1976) and outlining some of the prep that he did for Night of the Juggler on Furie’s instruction, which leads to an anecdote about getting a scare whilst reading the script for his next film, The Amityville Horror (Stuart Rosenberg, 1979), which was actually released before Night of the Juggler. We get an insider’s take on why Furie left the project and the ways in which Robert Butler’s directing style differed from his, and plenty of information on the production itself, which includes praise for young Abby Bluestone and for Mandy Patinkin (“the best role he ever had”), as well as the news that he did most (though not all) of his own stunts. He believes the film would have done better box office had it been more effectively sold. and is happy that it’s now been restored and is being re-released.

The Sweet Maria: Interview with Julie Carmen (14:21)

Also radiating youthful energy and repeatedly flashing a most bewitching smile, actor Julie Carmen recalls how thrilled she was when Sidney Furie insisted that is she didn’t get the role of Maria in the film then he would quit his job as director, only to discover that he had been replaced with Robert Butler by the time it came to shoot her scenes. She talks positively about working with James Brolin (“he was a beast in that movie!”), believes that the casting of New York character actors (she hails from the South Bronx) gave the film grit, suggests that the racist language in the film was indicative of the time, and tells story about the Doberman dogs that attack Dan Hadeya that will upset animal lovers. She also loved Cliff Gorman’s character and echoes Kim Newman and Sean Hogan’s words about him being a precursor to The Joker, and like Brolin is pleased that the film is being made available again.

Fun City Limits: Fear & Loathing in Hollywood’s NYC (28:33)

An excellent video essay by critic and film historian Howard S. Berger that looks at the sociopolitical evolution of New York City from the 1930s to the 1970s, and charts how this was reflected in the American cinema of the day. Illustrated with posters for, and clips and stills from, the films that are mentioned or discussed in more detail, it’s a fascinating and perceptive piece that touches on a wide range of key movies from the era. Particular attention is paid to Death Wish (1974), Taxi Driver (1976) and The Eyes of Laura Mars (1978), after which Berger moves on to Night of the Juggler, which he intriguingly describes as “perhaps one of the most unexpectedly compassionate films about New York City rot.”

Pandemonium Reflex: An Inquest into Sidney J. Furie’s Night of the Juggler (14:01)

Author Daniel Kremer, whose book Sidney J. Furie: Life and Films was published in 2015, recalls the jolt he received at the end of a day conversing with Furie about his work, when the director revealed that he had started but never completed a film shot and set in New York that turned out to be Night of the Juggler. It should come as no surprise that Kremer really knows his Furie films and thus has well-informed opinions on their style and themes that he is able to apply to the opening scene (including the chase) of Night of the Juggler. Kremer confirms that almost all of these were shot by Furie, and notes how the style he established continued to shape the film even after he was replaced by Robert Butler. Despite Kremer’s somewhat downbeat vocal delivery, this proves consistently interesting stuff, but the real gem here is the inclusion of an audio recording that Kremer made of his conversations with Furie, in which the director looks back at his experience on the film and details why he left after Brolin fell and broke his ankle. He also reveals that the visual style he developed for the film was to shoot the exterior and interior scenes with long lenses, which Robert Butler liked and continued to use and later employed when directing the pilot episode of Hill Street Blues, which became a defining aspect of the show and was itself a major influence on the crime and police series that followed.

The Meanest Streets (28:35)

A look at how the many New York locations in which Night of the Juggler was shot have changed in the intervening 45 years, hosted by Michael Gingold with audio contributions from the film’s production assistant Chris Coles, one that follows a familiar pattern by matching shots from the film with newly captured footage of the locations as they look today. While certainly interesting, this works better for some locations than others, sometimes because the new shots are framed slightly differently to those in the film, sometimes because the locations have so dramatically changed in the intervening years. Definitely worth a watch if you enjoyed the film, and while it does feel a little overlong, the length does allow for some fascinating and entertaining recollections of the shoot from Chris Coles, whose contribution alone makes this a must.

Trailer (1:51)

Very much a trailer of its day, with an almost random mix of character and action shots but not much information on the plot. It’s narrated in that serious and downbeat way that was common in trailers for 1970s American thrillers and dramas, but surprisingly doesn’t have a single note of music.

Stills and Poster Gallery

Five less than pristine promotional stills, several English language posters with the film’s regular title, one with alternative title, New York City Connection, two Japanese posters that see the title abbreviated to Juggler (Jagurā in Japanese), a poster with the Spanish title Secuestro en Central Park (which translates as Kidnapping in Central Park), and another that has the film labelled New York Killer.

Also included with the release disc is a Limited edition 40-page perfect bound booklet featuring new writing from Glenn Kenny, Barry Forshaw, and Travis Wood, and a pull-out poster and six lobby-card style postcards, but these were not available review.

final thoughts

A most worthy rediscovery for the launch of the Transmission label under the Radiance banner, Night of the Juggler may have its uncomfortable moments, but in so many ways it represents what was good and great about 70s American crime cinema, and for that alone this release should be celebrated. But of course, there’s more, as the restoration and transfer on both the Blu-ray and (especially) the UHD are first-rate, and the disc is bristling with excellent special features. Highly recommended, especially to those who, like me, still look back at 1970s American genre cinema as a golden age.