Identity theft

A brilliant but obsessed surgeon goes to extreme lengths to aid his injured daughter in EYES WITHOUT A FACE [LES YEUX SANS VISAGE], Georges Franju’s 1960 noir and horror-laced gem of French cinéma fantastique. In a review seriously delayed by work on the new site, Slarek recalls his first encounter with this personal favourite and enjoys its new UHD incarnation from the BFI.

It may seem a little redundant to start discussing how director Georges Franju misdirects the audience in the opening scenes of his masterly 1960 blend of noir and horror sensibilities, Eyes Without a Face [Les yeux sans visage], when a sizeable percentage of you reading this will have seen the film and probably know it well, but try to cast your mind back to your very first viewing and how you responded to what unfolded. These are my personal recollections, and newcomers to this extraordinary film can either elect to stay with me or skip to the final thoughts summary at the end if you want to go in completely cold, as there are even minor spoilers in the discussion of the special features.

In the black of night, a clearly agitated woman (Alida Valli) is driving rapidly along a tree-lined road to the tune of the sort of unsettling musical riff you might expect to hear if riding a sinister carousel operated by Mr. Dark from Something Wicked This Way Comes. The woman is clearly in a hurry to get somewhere, and it’s only when she adjusts the rear view mirror that we realise that she has a passenger in the back seat, one whose head is tipped forward and whose drooping face is obscured by a wide-brimmed hat. On first glance they look like an American movie gangster. Are they holding a gun on the woman in the front? It’s hard to say, but the driver seems more concerned by the headlights of the vehicle behind her. Is she being chased? Her concerned reaction certainly makes it seem like she is. Only then does it seem clear that the figure on the back seat is not holding the driver hostage but appears to have dozed off to sleep. The driver then pulls the car over to the side of the road and the vehicle that was behind her passes without incident, and her sense of rattled relief only increases our conviction that she’s in some sort of serious trouble.

The dozing rear seat passenger fails to stir as the car resumes its journey and even flops over to one side when the vehicle takes a corner a little sharply. Hang on, is this person asleep or have they been drugged into unconsciousness? Oh, if only. A short while later, the driver stops the car on the bank of a river whose water is flowing rapidly from a nearby weir and pulls the still immobile passenger from the car. As the driver drags the unfortunate individual along the grassy bank, we can clearly see that this is the body of a young woman and that she is almost definitely dead. The purpose of the journey is then grimly confirmed when the driver dumps the body into the river, then strides back purposefully back towards her car. At no point do we see the face of the victim. What, you might wonder, is going on here?

The film then switches from the black of night to a brightly lit corner of a white walled and ornately decorated room, where a middle-aged man takes a phone call that brings concerning news that he assures the caller he will communicate to ‘the professor’ as soon as he’s finished. We’re then transported into an adjacent lecture hall, where the professor in question, a stout, bearded man named Dr. Génessier (Pierre Brasseur), is educating an attentive audience on the challenges that the pursuit of physical rejuvenation present to the medical profession. As he brusquely exits the hall to loud applause, he is met by the man we saw taking the phone call, who informs him that the call was from the morgue and that he should head there right away. An urgent case needing the attention of this medical expert, perhaps? After curtly responding to positive comments from two of the older audience members, Génessier departs, and we overhear a woman remark that he has changed so much since his daughter disappeared. This puts a very different and worrying spin on the request that he immediately visit the morgue.

Meanwhile, over at the medical examiner’s office, the coroner (Michel Etcheverry) is conversing with Police Inspector Parot (Alexandre Rignault) about the likelihood that the body they have pulled from the river is that of Génessier’s daughter Christiane. For Parot, the evidence is clear. Prior to her disappearance, Christiane was facially disfigured in an automobile accident, an injury so severe that it may have prompted her to take her own life, which chimes with the lack of facial tissue on a body that has been in the water for 10 days. The coroner, however, is bothered by a couple of details, including the almost surgical nature of the girl’s injuries. When Génessier arrives, the coroner explains that the body matches the description of his daughter, and that the estimated time of the girl’s death coincides with Christiane’s disappearance. “The damaged face…” the coroner tells him, “only the eyes are intact.” Ah, you would be forgiven for thinking at this point, that explains this film’s enigmatic title. The quietly shaken Génessier confirms that the dead girl is Christiane, which leaves the understandably anxious Henri Tessot (René Génin) without an answer to what happened to his own daughter, Simone, who disappeared at approximately the same time as Christiane. “How odd I should have to comfort you,” Génessier tells him as he gets into car. “You still have some hope, at least.”

The next day on main city shopping street, two young women are crossing the road when an initially unidentified female figure slides into frame behind them and watches their every move. The fact that her appearance is announced by the same carnivalesque music theme that accompanied the opening scene encourages us to assume that this is the same woman we saw disposing of what we can now presume was Génessier’s daughter. This woman follows the couple and slyly eavesdrops on their conversation as they meet up with a young man, who quickly departs with one of the women, revealing as they do that their former companion, a student named Edna Grüber (Juliette Mayniel), is single and looking desperately for a room to rent. It’s here that we can clearly see that the older woman watching her is indeed the one from the opening scene. I don’t know about you, but at this point on my first viewing of the film, I was putting two and two together and coming up with what I thought was a solid four. In a complete break from the later societal and movie norm, I reasoned, we have a serial killer who is an outwardly ordinary middle-aged woman, one who appears to be fixating on young women and who is, based on the comment made to Parot by the coroner, mutilating the faces of her victims with surgical precision before killing them and dumping their bodies. She’s already killed Génessier’s daughter and probably poor Simone Tessot as well and now has her next target firmly in her sights. And that, if you are new to the film and want to find out for yourself whether my assumptions were correct, is where you should definitely stop reading and skip to the end, as I’m not going to be coy about how the story unfolds.

Eyes Without a Face first-timers will likely be a surprised by the next turn of events as I was back when I first saw the film, as we are then transported to a graveyard for the funeral of the late Christiane, and who should be seen standing beside Génessier and Christiane’s fiancé Jacques (François Guérin) but the woman I had pegged as a serial killer but who is here identified by attendees as Génessier’s secretary, Louise. Good grief, is Génessier not aware that she was the one who killed his daughter? As the guests and Jacques depart however, it’s the woman who is struggling to keep her composure, a rising sense of panic that is sharply curtailed when Génessier slaps her across the face. It soon becomes evident that these two are a lot closer than doctor and secretary, and exactly what is going on is clarified when they return home and Génessier heads upstairs and enters a bedroom in which a young woman is lying face-down on a couch with her face buried in a pillow. Although awake and conversant, she does not change her position at all to acknowledge Génessier’s entrance. We soon discover why when Génessier picks up a piece of paper from the table beside the couch, reminds her that he doesn’t like her snooping around, then attempts to explain why her name is on what turns out to be a memorial notice. The woman, we soon learn, is the real Christiane, and the funeral for her passing was effectively a sham, Génessier having falsely identified the body of Simone Tessot as being that of his daughter in order to bring the police search for her to a close. He worries that she is not wearing the mask he has presumably made for her and attempts to combat her increasing despair by assuring her that everything he has done and is doing is for her benefit, and that he will eventually succeed in what he is attempting to do. It’s a promise that the disillusioned Christiane no longer believes in.

As we soon discover, Génessier’s love for his daughter is so great that he has become determined to repair her damaged face, a task he is attempting by transplanting the facial flesh of a woman of similar age and facial build onto Christiane’s own, a highly advanced surgery that was the stuff of medical dreams back in 1960 and that would not successfully be performed in the real world for another 45 years. It’s a procedure that Génessier has been testing for some time on his underground kennel of caged dogs, and that, we discover, he has already successfully performed on Louise. The first attempt to provide Christiane with a new face was clearly a failure and resulted in the death of the unfortunate girl whose body we witnessed being dumped in the river in the opening scene.

It turns out that as well as disposing of the evidence of her beloved Génessier’s crime, Louise also scouts for new potential donors, listening in on their conversations and then using what she hears to earn their trust before luring them back to Génessier’s isolated mansion. It’s to this end that she befriends Edna, the girl we saw her stalking before we were aware of her true motivation, which she initiates by staging a chance encounter in a cinema queue, later meeting her in a café to reveal that she’s found her the lodging for which she has been so desperately searching. She then drives her out of central Paris to the Génessier abode, and to Edna’s credit she begins expressing doubts about the whole thing even before they arrive at their foreboding destination. By the time she’s in the house and introduced to Génessier, her initial apprehension has intensified to a level where she’d clearly like to leave, but the ever smiling Louise convinces her to stay long enough for Génessier to snatch her from behind and chloroform her into unconsciousness.

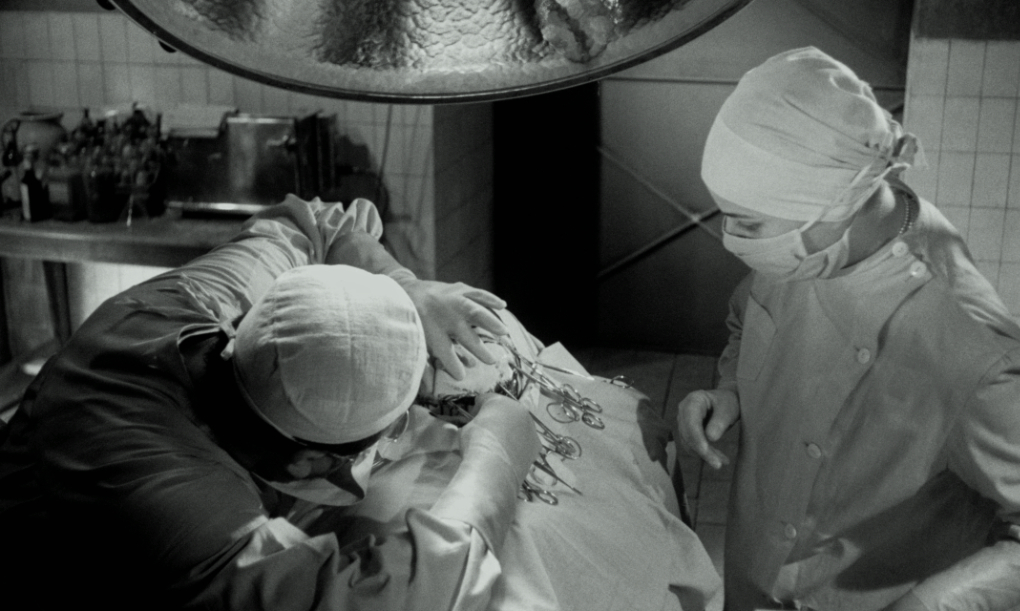

It’s then that we get to the scene that remains to this day its most frequently discussed, and with damned good reason, primarily for the content but also for the way it confounds narrative expectations in a manner that was spookily similar to another, even more widely analysed film released the same year. Just as Marion Crane was set up as the heroine, only to then be violently dispatched in the most startling scene in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, there’s a real expectation here that poor Edna will be rescued or find a way to escape her captors before she can suffer an equally gruesome fate. Even when shown strapped to an operating table with a surgical cloth fixed around her head with forceps, still unconscious and being quietly being observed by Christiane, it seems unimaginable that such a sympathetic character could become the subject of this monstrous procedure. But when Christiane removes her mask and approaches Edna to examine and stroke the face that she believes that she will soon be wearing, waking Edna and giving us out only blurred glimpse of the damaged face that she otherwise keeps hidden, Edna’s terrified scream sees that hope quickly fade.

The operation itself remains probably the most disturbingly realistic in genre history, methodically carried out by a man who genuinely seems to know how to perform this procedure, with no musical accompaniment and minimal bloodletting. We’re all familiar by now with the movie trick of faking a skin cut a prop knife that has a blood tube behind it, but it’s after the initial incision has been made, when Génessier lifts the skin to start cutting away at the muscles beneath with his scalpel in order to lift the flesh that I still experience a real shiver of horror. And that’s saying nothing of the moment the face itself is lifted off, which famously prompted several viewers to faint when the film was first screened at the Edinburgh Film Festival. Knowing this is being performed on an unwilling and innocent kidnap victim only adds to the sense that we’re witnessing something monstrous, and this, combined with the non-sterile operating theatre with its brick and tile walls, lagged pipes and glum lighting, can’t help but evoke memories of the medical experiments carried out by the Nazis during a war that many of those seeing the film on its release will have lived through.

The figure of a mad but gifted scientist or surgeon for whom human life is secondary to his ambition or ultimate goal goes all the way back to Mary Shelley’s seminal Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, and has certainly been a staple of genre cinema since Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, and probably beyond. Franju nonetheless still breaks with tradition by having his monster portrayed as – in some ways, at least – an otherwise normal man and a loving father who, having lost his wife a few years earlier and possibly been responsible for the car crash that robbed his daughter of her face and her will to live, is prepared to do anything to restore her to the beautiful and confident young woman that she presumably once was. It’s a character trait that epitomises the notion that while the more moral of us may regard all human life as sacred, we also, perhaps inevitably and unconsciously, tend to value the lives of those closest to us more than those to whom we have no direct connection. It’s an evolutionary bias on which amoral political opportunists regularly prey to create and stoke prejudicial attitudes to encourage otherwise fair-minded people to view those of a different race, creed, colour, gender or physical status as lesser human beings underserving of the rights and protections that we take for granted. And history has taught us where that can ultimately lead, all of which ties back into that geopolitical reading of the experiments and operations that Génessier performs in his grim, secret surgery.

There’s so much more that I could say about this extraordinary film, but so much has been written about it in such depth by analysts with more knowledge, more insight and more literary skills than I possess that I would effectively just end up unconsciously recycling their words, and to some degree know that I already have. I’ve certainly not seen enough of Franju’s previous short films – or indeed his debut feature, Head Against the Wall (La tête contre les murs, 1959) – to start exploring the sort of cinematic evolution that the learned contributors to the special features on this disc are able to do with such confidence. What I will say is that my reactions and readings of the elements discussed above, although also expressed by many others before me, are all my own, first viewing responses that this UHD release has reawakened with some gusto. There’s so much to admire here on both sides of the camera. As a storyteller, Franju is never in a hurry, occasionally focussing on seemingly inconsequential moments that nonetheless linger in the mind and feel designed to prompt a search for secondary meaning. Despite the subject matter, there’s not a whiff of sensationalism to the handling of even the most potentially grisly moments. Realism is key here, the result being that it all feels so disturbingly plausible, something that even extends to a sequence where a character is attacked by dogs, which may be the most believably staged such scene that I can readily recall. Yet Franju is still able to lace the tension and horror with genuine poetry, transforming the theoretically overt symbolism of covered mirrors and caged doves and dogs and their eventual release into moments to savour and be unexpectedly moved by. Mind you, he’s working from a strong foundation provided by screenwriters Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac (writing as Boileau-Narcejac), from an adaptation of Jean Redon’s novel of the same name by Redon and Claude Sautet, with dialogue credited to Pierre Gascar. By this point Boileau and Narcejac already had some serious film pedigree, their novel Celle qui n’était plushaving been adapted for the screen by Henri-Georges Clouzot in 1955 as Les diaboliques, while their book D’Entre Les Morts had been the basis for Alfred Hitchcock’s seminal 1958 Vertigo.

In building an atmosphere of escalating nightmare and dread punctuated with moments of pure surrealistic poetry, Franju is aided no end by the striking noir-leaning monochrome lighting camerawork of German cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan (here credited as Eugen Shuftan), a master of his craft who started out as a visual effects artist on the likes of Abel Gance’s Napoleon and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis (both 1927), and who the year after shooting Eyes Without a Face won the Best Cinematography Oscar for his work on Robert Rossen’s The Hustler (1961). And while key scenes may play out solely with natural sound, this should not in any way diminish the contribution of composer Maurice Jarre, another later Oscar-winner (Lawrence of Arabia (1963), Doctor Zhivago (1966), and A Passage to India (1985), all for David Lean), who creeps us out with that carousel theme that accompanies Louise as she hunts for a new victim or disposes of a body, and whose music contributes so much to the poetic ambiguity of the closing moments. And then there’s Christiane’s mask, as iconic a creation as those worn by later genre superstars Jason Voorhees and Michael Myers, but all the more disquieting here for being such a close representation of the face that previously sat beneath. Just flexible enough to act like a restrictive second skin, its expressionless, ghostly white appearance gives Christane an almost doll-like appearance and lends her masked scenes a genuinely Jean Cocteau-esque feel.

The performances all impress for individually specific reasons. As Génessier, Pierre Brasseur is able to convince one minute as an arrogant genius whose emotions are so buttoned down it has transformed him into an amoral monster, then the next as a loving father whose sense of guilt is so great that there is nothing he will not do to repair the damage inflicted on his daughter. As his assistant, his partner, and his only successful transplant to date, Alida Valli manages a similarly delicate balancing act as Louise. Surreptitiously stalking victims, cheerfully deceiving them and leading them to their doom, she coldly and efficiently assists in Génessier’s surgical procedures, but remains warmly encouraging when attempting to comfort the sometimes despairing Christiane, and intermittently her calculating exterior slips to reveal the emotionally vulnerable woman beneath. Best of all is Edith Scob, who as Christiane is largely robbed of facial expression by her mask, and despite verbally expressing her feelings, it’s what she communicates with her eyes, her gestures and the movements of her body that reveal the most about how she truly feels at any given point in her story arc. It’s essentially a mime that is so sublimely performed that it never feels like one, and is key to why, despite her albeit passive complicity in her father’s crimes, she remains a figure of audience sympathy. It’s a testament to this aspect of Scob’s performance that on my first viewing I suddenly realised that I was rooting for the facial graft to take, despite having been horrified just a short while earlier by the terrible price that its unwilling donor had paid – I even had a little “oh no!” moment when Génessier spots that the first sign that the graft might actually be starting to fail. I’ll also give a shout out to the supporting cast, particularly Juliette Mayniel as Edna, and Béatrice Altariba as Paulette Meroudon, a shoplifter whom the police convince to act as bait in their belated investigation, both of whom deliver the most convincingly terrified screams in genre movie history.

I’ve rambled, again. This is what happens when you task yourself with discussing a favourite film about which, by this point, there really is little that hasn’t already been said. It’s a film that genuinely haunted and startled me on my first viewing in my younger days and much of its imagery set up home in the back of my brain and has been living there happily ever since. Returning to it again after a break of several years, Eyes Without a Face has lost none of its power, its poetry, or its darkly magisterial beauty, and by thunder, that sequence still makes me shudder with horror even today. I’m only thankful that I’m not scheduled for surgery of any description any time soon.

sound and vision

To quote the accompanying booklet:

Eyes Without a Face was scanned and restored in 4K resolution by Gaumont

using the original 35mm negative and is presented in high dynamic range with

Dolby Vision in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1 and with original mono audio.

As you are doubtless aware, even if you’ve never seen the film (the frame grabs do tend give it away), Eyes Without a Face was filmed in black and white, and when I say black and white I mean BLACK and WHITE. I do not have the previous Blu-ray or other disc releases of the film to use as a comparison, but there are whole sequences here – primarily nighttime exteriors – when the contrast is so beefy and the blacks so solid that they practically obliterate detail on dark surfaces and clothing in unlit areas. I’m presuming that this was a deliberate decision on the part of Franju and cinematographer Eugen Schüfftan to give these scenes a noir crime drama feel (which it absolutely does), and on my OLED screen those blacks are some of the inkiest I’ve yet seen. There’s also just a little burn-out on a few of the highlights in these scenes, and once again, I’m not qualified to state with any authority whether this was intended or a feature of this particular transfer.

Far easier to judge are the daylight exteriors and the well-lit interior scenes with Christiane, whether the Dolby Vision HDR helps deliver a generous and very pleasing contrast range. There is some variation in the sharpness of the image, with a slight softness to a few shots, which again may be how they have always looked, and the vast majority are sparklingly crisp. And yes, there is a fine film grain visible throughout, and all signs of dust or damage have been eliminated.

The original French mono soundtrack is presented in DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 and is consistently clear and free of distortion and shows no obvious signs of wear.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default but can be switched off if your French is up to it. Is mine? Non, ce n’est pas le cas.

special features

The majority of the special features on this new BFI UHD release of Eyes Without a Face have been carried over from the BFI 2015 Blu-ray/DVD Dual Format release. This disc does, however, include a newly commissioned commentary by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas, and it’s a cracker. The special features listed below have been covered, as ever, in the order in which they appear on the disc menu, and all are 1080p, except the trailer, which is 4K.

Commentary by Tim Lucas

Recorded in 2014 and imported from the previous Blu-ray release, this commentary by Tim Lucas, the founder and editor of Video Watchdog magazine and a fantastique cinema specialist, kicks off with the admission that Eyes Without a Face is the horror film that is closest to his heart, and that it represents horror at its most exquisite, its most cruel, and its most savage. Nice. He examines specific sequences in detail, notes that trains and birds are signature features in Franju films, discusses individual characters and provides details on cast members, and reads quotes from relevant interviews and reviews. There is some compelling analysis here, with Lucas delivering a brief but fascinating deconstruction of the short sequence in which a car has to wait at a railway level crossing, and when discussing the performance of Edith Scob as Christiane, he finds intriguing parallels in two episodes of The Twilight Zone. There’s so much more of real interest here.

Commentary by Alexandra Heller-Nicholas (2025)

Newly recorded for this release, this commentary is by film critic and author, Alexandra Heller-Nichols, whose many books include the particularly relevant Masks in Horror Cinema: Eyes Without Faces. Describing Eyes Without a Face up front as “one of the most captivating and terrifying and downright beautiful films I’ve seen,” Heller-Nicholas quickly dispels any concerns that she will be retreading territory already covered by Tim Lucas in his commentary with a meticulously researched examination of the film, its makers, its impact, and its influence, as well as the works from which Franju himself drew inspiration. A wide range of material is cited, quoted from, and heartily recommended for later reading, and the relevance of Franju’s previous film, Head Against the Wall (La tête contre les murs, 1959)1 and his 1949 documentary short, Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes) is discussed in detail, as is the origin of Eyes Without a Face and its influence on subsequent horror cinema. Unsurprisingly, given the title of the above-cited book, the role of masks in genre cinema is also explored in fascinating depth, as are religious and geopolitical readings of the film, and the question of whether Christiane is a victim or a victimiser or both is addressed. This is just a sampling from a rich and hugely educational commentary.

Mark Kermode Introduces Eyes Without a Face (2:13)

A by-now familiar sight on BFI releases, this brief introduction by critic Mark Kermode to what he describes up front as one of his top ten films of all time was recorded in 2016 as his BFI+ Player choice of the week. There are some spoilers here for newcomers unaware of where the story goes.

For Her Eyes Only – An Interview with Edith Scob (17:19)

This interview with actress Edith Scob was recorded in 2014 and is a most welcome inclusion here. She recalls first working with director Georges Franju on La tête contre les murs, speculates on why she was chosen for the role of ‘The Singing Madwoman’ in that film, remarks that Franju was sensitive to architectural elements, and recalls that he behaved subjectively on set, giving his full attention to the actors playing characters he liked and all but ignoring those that he didn’t. She suggests that she was offered the part of Christiane in Eyes Without a Face because Franju wanted someone that the public wouldn’t instantly recognise, shares recollections of her co-stars Alida Valli (“I found her fascinating”) and Pierre Brasseur (“got along with Franju like nobody’s business”), and discusses the three different masks that she wore throughout the filming, neatly describing the one she had to keep on all day as “a portable jail.” She also notes how the surgical procedure in the film was “strangely premonitory” in its anticipation of the now widespread use of reconstructive and cosmetic surgery, but claims that the latter is not for her as she wants to experience the process of ageing.

Les Fleurs maladives de Georges Franju (46:20)

A 2009 documentary on Georges Franju by Pierre-Henri Gilbert built around interviews with a sprinkling of his former collaborators and some of his admirers. These include actress Edith Scob, Judex (1963) and Nuits rouges (1974) screenwriter Jacques Champreux, assistant director on Franju’s 1970 The Demise of Father Mouret [La faute de l’abbé Mouret], Bernard Queysanne, cineaste Jean-Pierre Mocky, and Kate Ince, the author of Georges Franju – Au dèla du cinéma fantastique. We even get brief tributes from acclaimed directors and Franju fans Robert Hossein and Claude Chabrol. Although the focus is Franju, his career, his personality, his outlook, his approach to filmmaking, and his relationship with actors, the documentary revolves primarily around Eyes Without a Face, many extracts from which are included, even when other films are under discussion. There’s a lot of ground covered here, and despite some crossover with the other special features (there’s a story about audience members fainting at the Edinburgh Film Festival screening that I think is in just about every extra here), the fact that these stories are told here from a personal perspective is refreshing nonetheless. The content is fine, but – and this is just me on a personal gripe – director Gilbert employs an all-too common filming and editing technique that really gets on my tits, one that involves shooting interviews from two very different angles and then bouncing randomly between them for no earthly reason other than the presumed belief that the audience has the attention span of a hyperactive flea. The presence of multiple jump-cuts in the interviews and the fact that these angle switches occur mid-sentence confirms that they’re not being used to hide edits to the conversations, and nowadays this is what the editing would look like if you gave the footage to AI software and told it to make cuts wherever it pleased. I’m not specifically having a go at Gilbert here, as he’s following a by this point established and hugely annoying trend, one that I sincerely hope is going out of fashion. If you find this technique as distracting as I do, do what I did and focus your eyes on the subtitles, because the conversations themselves are definitely worth following.

Trailer (3:49)

An oddly structured original French trailer (early on, Pierre Brasseur is shown watching himself from an upstairs window as he carries a body in the grounds below) that leans into the mysterious, something that is picked up by a narrator who pops up halfway through to ask a series of questions that he doubtless hopes you’ll visit the cinema to see answered. Despite the broken-mirror narrative, there are spoilers here for first-time viewers.

Monsieur et Madame Curie (14:09)

A 1956 drama-documentary short by Georges Franju that charts the process that led to the discovery of radium by Nobel Prize winning scientists Marie and Pierre Curie, who are here played by Nicole Stephane and Lucien Hubert. It provides a welcome peek at the realistic approach favoured by Franju and discussed elsewhere in the special features, being free of dialogue and with narration drawn from Marie Curie’s biography of her husband. Franju’s sober observational approach works well for the subject matter and is occasionally punctuated with poetically framed and lit close-ups of Marie at key stages of the experimentation. The late film, post-discovery scene in which the family enjoys a holiday in the countryside (one that would come to a tragic end), one that plays out to a classical piano score, almost feels like a sequence from one of Ken Russell’s later films for TV’s Monitor arts series. Unlike the main feature and Le Priemière Nuit (see below), this has not been fully restored, so there is a fair amount of movement of the image within the frame, some dust spots and minor damage, and the soundtrack has a background hiss and the occasional pop. For me, this only added to the sense that this was a genuine historical document rescued from the vaults.

La première nuit (19:38)

Made in 1958, this was the last short made by Franju before his feature debut the following year with La tête contre les murs. Dedicated “to all those who have not disowned their childhood… and who, at the tender age of ten, discovered both love and separation,” this beautifully told tale revolves around two schoolchildren from different social classes who have developed a crush on each other. The dark-haired boy is driven to school in an expensive car by the family chauffeur, while the blonde-haired girl rides the Paris Metro. When the chauffeur briefly pauses on the journey home one night to buy a newspaper, the boy sneaks out of the car and descends into the Metro just too late to see that the girl departing on her train. Initially fascinated by the subterranean bustle and activity, the boy remains below ground until all of the passengers have departed, then falls asleep on a now idle escalator, and in his dreams the Metro is transformed into a surrealistic metaphor for love and loss.

Gorgeously photographed by night in the labyrinthine Metro subway tunnel system by Eugen Schüfftan, La première nuit is a bewitching blend of documentary realism and poetic fantasy, a seamless interweaving of opposing elements that is perfectly captured by the evocative score by Georges Delerue. The film is initially fascinating for its record of the Metro trains of the late 1950s, with their box-like cars, rectangular windows and latch-lock doors, and at one point it plays briefly like a noir thriller. But it’s when we move into the dream world that the film is at its most bewitchingly magical, as trains glide silently through the station with the girl as their only passenger and the boy runs alongside unable to reach her. In what for me is the film’s most astonishing and captivating sequence, the boy rides an empty and driverless train, and another pulls up alongside and matches its speed, and the boy and girl find themselves facing each other on different trains, almost able to touch but separated by glass and metal. Then, most unexpectedly, the train the girl is riding seems to rise into the heavens as the track on which it is running heads up to surface level while the boy’s train remains underground. It all appears to have been done for real, and I found myself wondering how the hell Franju and his team were able to pull this off. A wonderfully executed, poetic, and dialogue-free work that beautifully evokes a dream world that I genuinely recognised – if you only know Franju for Eyes Without a Face, just see what this remarkable filmmaker could do with a basically simple idea.

Unlike Monsieur et Madame Curie, La première nuit was restored in 2014 from the original 35mm camera negative by the Éclair Group (picture) and L.E. Diapason (sound). It’s framed in the Academy ratio of 1.33:1 and looks terrific, and the mono soundtrack is clear and free of damage.

Booklet

Leading the way here is an essay enticingly titled Fantasy, Fairy Tale, and Feminism? Eyes Without a Face by Kate Ince, who is professor of French and visual studies at the University of Birmingham, has written and edited books on Georges Franju and French-language cinema, and guest-edited journal issues on post-national cinema and French women’s filmmaking in the 2000s. She was also a contributor to the above-detailed documentary, Les Fleurs maladives de Georges Franju. Ince acknowledges the geopolitical readings of the film but admits to being more interested in its gender politics, which she explores before moving onto the film’s UK and US release and critical reception, with particular emphasis on the positive reaction of Pauline Kael.

Next is an abridged version of the Les Yeux sans visage chapter from the Raymond Durgnat book Franju, a most welcome inclusion given the number of times it is referred to and quoted from by Alexandra Heller-Nichols in her commentary. Durgnat is an acknowledged authority on Franju and his films, and this detailed assessment of Eyes Without a Face is thus unsurprisingly thoughtful, acutely observed, and persuasively argued. He discusses how Franju transforms recognisable horror tropes into poetry, as well as his purposeful attention to detail, the relationship that develops between the viewer and Christiane, the reaction of the cinema audience with which he saw the film, how it anticipates later medical procedures, and so much more.

After this we have a useful piece by writer, broadcaster and filmmaker, Kevin Jackson, which looks at the writing partnership of Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the now celebrated film adaptations of their work by Henri-Georges Clouzot and Alfred Hitchcock, and their contribution to the screenplay of Eyes Without a Face. Following this is a short but interesting piece by Roberto Cueto, an associate professor of audiovisual communication at the Carlos III University in Madrid, which outlines how Franju discovered the music of Maurice Jarre, with whom he would collaborate on several films, including, of course, this one.

Credits for the special features but – for the first time in my experience – not the main feature, lead into detailed coverage of the two Franju short films included on this disc, as well as a brief but useful introduction to them, by managing editor at Sight & Sound, Isabel Stevens. Brief details of the restoration are included, and the booklet is illustrated with promotional stills.

final thoughts

Yes, this is late, and I’m guessing that 4K enabled fans of this film will have already purchased this disc, but if you are 4K ready and you haven’t yet taken the plunge then I’d definitely suggest this disc is worth having. Assuming the punchy contrast is as Franju intended, the transfer is top notch, and the special features are of collectively superb. Of course, if you have the previous BFI Blu-ray then you’ll already have most of what is on offer here, so the decision of upgrade will be based purely on the transfer and the (excellent) Alexandra Heller-Nicholas commentary. How this image quality on this disc compares to the one on that Blu-ray or the newly released American UHD from Criterion will be a subject for those with deeper pockets and greater expertise in this field to tackle at this stage, but I’m happy enough with this disc to give it a hearty recommendation.

Eyes Without a Face

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

Add Your Heading Text Here

- Although she initially refers to La tête contre les murs by its standing English language title, Head Against the Wall, Heller-Nicholas afterwards uses the title Head Against the Door. I’m not sure if she is misspeaking here or if this is an alternative title that I’ve not previously encountered. For the record, the actual translation of the title is, I believe, the plural Head against the Walls.[↩]