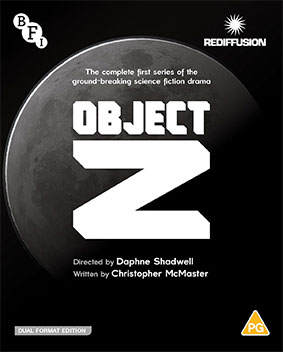

Object Z

Broadcast in 1965 and never repeated, the science fiction serial OBJECT Z is released on dual-format by the BFI. Gary Couzens watches the skies.

A team of scientists, led by Professor Ramsay (Ralph Nossek), June Challis (Margaret Neale) and Robert Duncan (Denys Peek), report that a large object, some six miles across, is on a collision course with Earth. Prime Minister Sir John Chandos (Julian Somers) breaks the news to the public and initiates emergency procedures, with lots drawn so that a tenth of the population can be admitted to shelters, the rest facing certain death. As journalist Peter Barry (Trevor Bannister) and his assistant Diana Winters (Celia Bannerman) report, the UK, USSR and USA cooperate on a rocket, containing a bomb bigger than anything yet exploded on Earth, in an attempt to destroy or divert what is now known as Object Z. There are six weeks until the possible end of life on Earth…

Object Z was a science fiction (SF from now on, not “sci-fi” – I’m old-school) serial, broadcast on Tuesday afternoons on the ITV network from 19 October 1965 for six weeks. It was broadcast at the end of children’s viewing time in a half-hour slot (5.25-5.55pm, followed by the news), also attracting adults who were back in time from work. Yet it is a very odd fit for children’s viewing, of which more in a while. As it was never repeated, for most people (including myself, who turned a year old in the month of its first broadcast) it has existed as a title in reference sources with little or no opportunity to view it. However, due to the vagaries of television preservation of the time it exists in full, so we can, thanks to this release brought to you as part of the BFI’s licensing of the catalogue of Associated-Rediffusion (A-R), the company which made it.

ITV launched seventy years ago, on 22 September 1955, an advertising-funded channel as opposed to the licence-fee-funded BBC, whose then one channel had had a monopoly of British television broadcasting up to that point. ITV was structured regionally, with each part of the country having its own franchised company, though programmes were often shown over the entire network. A-R held the franchise for London and the South-East on weekdays, while ATV had it for the weekends. At first they were the only ITV companies on the air until February the next year, when the Midlands (also ATV) came on board. It took until 1962, when Channel started broadcasting to the bailiwicks of Guernsey and Jersey, that the entire ITV network was in place. ITV immediately set out to offer an alternative to an often stuffy and frankly class-based BBC. The BBC clearly saw it as a threat and aimed to spoil opening night by broadcasting high drama on the radio soap The Archers, with Grace Archer’s death in a fire. Inevitably there were accusations that ITV was dumbed-down and downmarket, and over-reliant on American imports, but the bigger companies set out to make programmes at least as good as the Beeb’s, especially in drama. A-R (who renamed themselves simply Rediffusion in 1964) was one of them.

SF was a popular drama genre on television and had been since early in television’s life in 1936, with examples on the UK’s screens before World War II shut the television service down. (See below for some examples, in the discussion of Kevin Lyons’s commentary track and its footnote.) Some of this was undoubtedly for adults – Quatermass II (1955, the first episode a month after ITV’s launch) was famously appended with the warning that it was “not suitable for children or for those of you who may have a nervous disposition” – but younger viewers were catered for as well. Chris (here billed Christopher) McMaster spent most of his career in television as a director and producer, in the former capacity a regular on Coronation Street. However, he was also a writer and as such pitched Object Z as a SF serial. It was apparently the director Daphne Shadwell who suggested that the story could be a serial for children, as A-R were looking for good drama for younger viewers. How much was changed is a good question, as Object Z has few markers of a typical show for children. If there weren’t children (or at least teenagers) as the leads, there might be puppets or animals. However, everyone on screen is an adult, there are no puppets and the only animal we see is Paul Bazaine’s (Bernard Kay) dog. As well as the noticeably bleak middle section where most of the cast is waiting for the possible end of the world and their demises, the serial includes philosophical and political themes. These include the character of Keeler (Arthur White), who would now be called a far-right nationalist and populist, modelled on the then-living Oswald Mosley, first seen on a television set ranting to a rally of his Action Party in Trafalgar Square. This is a serial which admirably talks up to the older children who are its target audience. Other than the sequel Object Z Returns, McMaster’s only other writing credit is for an episode of the 1979 series Park Ranger. Also for children’s television, he created, produced and sometimes directed the adventure series Freewheelers (1968-1973), made by, as was Park Ranger, by another ITV franchise, Southern. He died in 1995, two days before his seventieth birthday.

Object Z is almost entirely studio-bound, with exteriors represented mostly with stock footage which is very noticeable when watched in HD, as on this disc. In some cases actors performing front of studio flats (see the conversations between two men and two women in the second episode for a particularly obvious example). On the other hand, the production aimed to be as scientifically realistic as possible. The credits of the final episode acknowledge the assistance of the Astronomer Royal and Hurstmonceaux Observatory. Germans speak German and Russians speak Russian, translated as necessary by interpreters. Also, we have an American actor (Robert O’Neil) playing the US President and a Russian (Dmitri Makaroff) as the Soviet Premier. The exception to all this is Milton Johns as a Bedouin chief in the final episode, a scene in a very obvious desert set. As was common with a lot of video-shot drama of the day, it was recorded “as live” in a single evening, and in this case broadcast the next day. Editing was minimal, retakes rarely possible, and actor fluffs were not a reason for them. Robert O’Neil commits a noticeable one in Episode 5. The director was Daphne Shadwell, who had begun her career at the BBC but moved to A-R as it began. She worked in light entertainment as well as drama and had a particular affinity for children’s television. As well as the present serial, she is represented on BFI disc as the director of Do Not Adjust Your Set.

Needless to say, some of Object Z is “of its time”, but not all. The serial followed Quatermass in having one of the two major female roles being a leading scientist, June Challis, played by Margaret Neale, not there to scream and be rescued as (for example) Doctor Who did quite often. After the serial begins with her and Robert Duncan (Denys Peek), they and their nicely understated love story tend to revert to the background. While Diana Winters at first seems to be there to get the coffee and take dictation, as played by Celia Bannerman (her screen debut), she’s quite resourceful. Trevor Bannister, for many of us forever associated with comedy as Mr Lucas in Are You Being Served? a decade later, shows he’s as adept in drama, as in fact this serial’s tough and sometimes two-fisted leading man.

Given that Object Z is due to hit during the third episode, it’s not hard to realise that there’s a twist. And there is – the next episode’s title is not much of a spoiler, especially given that purchasers of TV Times would have been aware of it for up to a week beforehand. However, there are at least two more turns before we’re done, and I’ll let you find those out for yourself. One of them is at the close of the final episode, followed by a The End credit…but it leads us straight into the sequel, Object Z Returns. Due to the success of Object Z, that sequel followed in short order, also written by McMaster and directed by Shadwell and with the principal cast except Celia Bannerman returning. It was broadcast, also on Tuesday afternoons, in six episodes from 22 February 1966. The serial is sadly lost, but it seemed to have been quite prescient, dealing with what would now be called climate change, with the threat of a new Ice Age. (This follows the pattern of the entirely surviving BBC serial The Andromeda Breakthrough (1962) following straight on from the mostly-lost A for Andromeda (1961), also with a change in the principal cast – there, Susan Hampshire taking over from Julie Christie in the title role – and also dealing with climate change. Both serials were also ahead of their time in their depiction of women in a scientific working environment.)

Object Z has an obvious low budget, but few allowances need be made for its age, and certainly not for its being broadcast as children’s drama. The BFI are due to release more items from the A-R catalogue, but this will do very well to be going on with.

sound and vision

Object Z is released by the BFI in a dual-format edition, Blu-ray and DVD. This review is from a checkdisc of the former, which is encoded for Region B only, so the DVD (not seen) will be Region 2. The episodes were classified by the BBFC individually, so the PG certificate this disc bears is for for “mild threat” in Episode 2. All the other episodes were passed at U. The episodes are as follows:

- The Meteor (25:01)

- The World in Fear (24:31)

- Flight from Danger (24:10)

- The Aliens (24:27)

- Too Late (24:20)

- The Solution (24:25)

There is a Play All option in case you want to binge-watch, a concept or indeed possibility that didn’t exist in 1965. The episodes are complete with Rediffusion idents at the start and finish of each episode, and End of Part One/Part Two bumpers on either side of where the commercial break would have been.

The episodes were recorded on 625-line black-and-white PAL videotape, with film materials (almost all stock footage) telecined at the time of recording. Although BBC2 had been launched in 1964 as a 625-line-only service in preparation for colour broadcasting (which arrived in 1967 on that channel), BBC1 and ITV still broadcast in 405 lines as well, and it’s likely many of the audience for Object Z in 1965 were watching that way. However, on those channels, and even in black and white, drama productions were beginning to be made in 625 rather than 405, though ITV shows from various regions were still in 405 in 1969, the year when it and BBC1 launched their colour services. The broadcast tapes have long since been wiped, but the serial exists on 16mm film telerecordings, often used for selling shows abroad. The transfers on this Blu-ray were scanned at 2K resolution from these telerecordings. They are in the original ratio of 1.33:1 and run at 25 frames per second, the correct speed for PAL television broadcasting. The results are a little soft, as you might expect from 16mm film, and don’t have the sharpness native video would have. There are instances of minor damage, such as splices and some speckles, but nothing too distracting. Given that the original broadcast tapes are wiped, this is as good as this can get. For technical reasons I have been unable to take screengrabs from the Blu-ray checkdisc, so the illustrations to this review are BFI publicity stills.

The sound is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0 and is clear and well-balanced. Subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available on all episodes. They are accurate, with only a few typos which are anachronistic rather than incorrect spellings: “Ms Challis” instead of “Miss Challis” in Episode 1 and “tonnes” (metric) instead of “tons” (imperial), especially as other imperial measurements such as pounds are used.

special features

Commentaries

Six episodes, six commentary tracks, four solo and two by duos, with a Play All option. With a TV serial like this and just twenty-four or -five minutes to fill per episode, this does carry the risk of a lot of repetition across the separate tracks. While there is some, it’s clear that this has been avoided for the most part. (For example, in Episode 1, after mentioning Celia Bannerman Jon Dear makes a point of saying nothing more and refers us to the Episode 6 track where she takes part.) Four of the commentators also contribute to the booklet, so there will also be repetition there, if you have a first pressing copy of this release with said booklet, as you should.

Jon Dear begins by introducing us to this now-obscure serial which does not have a Wikipedia page. (The page for what is rendered as Object-Z is about something else entirely.) He also gives us a spoiler warning, so listen to this after watching the entire serial. He wonders if Chris McMaster was influenced by the 1939 novel The Hopkins Manuscript by R.C. Sherriff (now best known for his World War I-set play Journey’s End), which has a similar plot. (Not mentioned, but you wonder if someone in the production had seen the 1951 film When Worlds Collide.) Dear gives us a runthrough of McMaster’s career and a nod to the circumstances of the serial’s production, recorded as-live a day before broadcast, more details of that elsewhere.

BFI Southbank Archive TV programmer Dick Fiddy is next. He concentrates more on the history of A-R and its base at Wembley Studios, and in particular its lack of children’s shows which resulted in Object Z being rewritten (by whatever extent it was) for a family-viewing slot. He also discusses how the programme, being shot as-live, has a few hangovers from the era of actual live television drama which had almost entirely ended by 1965 (Z-Cars, which began in 1962, was one of the few shows still being broadcast live). For example, the conversations between the two men and the two women in this episode would have acted as a transition scene featuring peripheral characters so that the principals had time to be in position for the next scene with a costume change if necessary.

Episode 3 features the duo of William Fowler and Vic Pratt, familiar from many a BFI Flipside release. As you may expect, Pratt in particular extols the Sixtiesness of the show (made before he was born, I suspect), from the “groovy” jazzy theme tune and some of the costumes from the then-nascent Swinging London – in particular Diana’s “kinky boots” as they are referred to onscreen. Both men give a lot of context to the show in what was happening in the world outside, in both popular culture and elsewhere. (The Rolling Stones were at number one with “Get Off My Cloud” for part of the serial’s run, though Fowler doesn’t mention that when it started, top of the charts was Ken Dodd with “Tears”, not a very Sixties sound but that year’s best-selling single.) That elsewhere includes politics, with the feel of impending apocalypse of this episode especially evoking recent events such as the Cuban Missile Crisis and the anti-Bomb Aldermaston marches and current ones such as protests against the Vietnam War. They also wander how much television for children namedrops the likes of Socrates, then or now.

Episode 4 is in the hands of Dr Elinor Groom (or Ellie Groom, as she introduces herself, and she’s billed that way on the booklet cover), a curator of television for the BFI National Archive. She provides an equally enthusiastic commentary which tends to be scene-specific. However, she spends more time than others on Daphne Shadwell, whom she has researched and about whom she has written a piece in the booklet, summarising her life and career. She suggests that Object Z is a reversal of the usual pattern that female characters are often there to provide or abet necessary exposition; here, it’s the men, scientists and politicians especially.

Kevin Lyons is next, for Episode 5. Lyons is the editor of the online Encyclopedia of Fantastic Film and Television, and he takes a different tack to other commentators, putting Object Z in context with other small-screen SF. That didn’t begin in 1953 with The Quatermass Experiment, as many might think. As the surviving two episodes of that serial are the among the earliest examples of live television drama to exist (and the earliest surviving episodic drama), we may be forgiven for overlooking productions of Karel Čapek’s R.U.R. in 1938, of H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine (1949), J.B. Priestley’s play Summer Day’s Dream (also 1949) and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1950). All of which were broadcast live and sent out into the ether without being recorded, so are now lost to us short of the invention of time travel or broadcast-quality memory retrieval from a now-elderly viewer. That was also the case with Stranger from Space, seventeen ten-minute episodes from 1951 and 1952, which beat Quatermass to the punch as the first original SF serial on British television. Lyons goes on to mention other SF series or single dramas from the time of Object Z for further context, which I’ll leave for a footnote1 to save space. It’s quite a checklist for the interested to track down those which still exist. As well as all that, he mentions Max Ehrlich’s 1949 novel The Big Eye as a possible predecessor to Object Z. As the character of Keeler appears quite extensively in this episode, Lyons talks about how he is modelled on Oswald Mosley. Keeler appears in two episodes of this series, but was in all six of Object Z Returns.

Finally, Episode 6 gives us another change of tack. With a release like this, of something made sixty years before, finding someone who was involved in its making to interview can be difficult, as they would now be elderly and possibly no longer compos mentis. (I’m not aware of Daphne Shadwell’s willingness or ability, but she doesn’t participate in this release, as she didn’t for the BBC’s 2019 release of Do Not Adjust Your Set.) However, Celia Bannerman is still with us and she and Toby Hadoke provide the commentary on this final episode, which as Hadoke (ubiquitous on Doctor Who disc releases) points out was broadcast on 23 November, Doctor Who’s second birthday. Bannerman had studied at the Drama Centre and had worked on stage, but this leading role was her screen debut at the age of twenty-one. She hadn’t seen the serial since its broadcast until she was approached by the BFI to take part on this disc. The schedule for each episode of Object Z was as follows, per episode: rehearsals on Wednesday and Thursday, a run-through on Friday, the weekend off, camera rehearsals on Monday with recording that evening, and the finished product broadcast on Tuesday afternoon. That was as pressurised as it sounds. However, the second half of episode three had to be redone for technical issues. Bannerman also talks about her later career, including much work as a children’s acting coach on film productions.

In Search of Sierra Nine (7:19)

Sierra Nine was an earlier SF series from A-R. It was broadcast in thirteen episodes on Tuesdays in the same slot asObject Z would later have (5.25-5.55 pm) from 7 May 1963. It was written by Peter Hayes and directed by Marc Miller and shared the services of designer Andrew Drummond with the later serial. It featured a team set up to counter scientific threats, with Sir Willoughby Dodd (Max Kirby) in charge and Peter Duncan (David Sumner) and Anna Parsons (Deborah Stanford) there to provide the derring-do. Like Doctor Who, which launched on BBC1 six months later, it was a series of serials, with stories running for four, three, two and four episodes. All that survives is the second episode of that two-parter, “The Elixir of Life”, broadcast on 2 July, without its soundtrack, so over to the lipreaders out there. This item shows us edited highlights of that episode with a commentary by Vic Pratt, who discusses the background and premise of the series, which looks suitably ambitious on a low budget. Sadly we can’t see any of it now.

Episode 1 Shooting Script (12:00)

Self-navigating, though you can skip to particular pages as each is a separate chapter stop, thirty-six of them.

Image gallery (4:50)

Also self-navigating. After some stills, we have Rediffusion’s press release, synopsis and television listings information (presumably for TV Times), then a fair amount of correspondence. This begins with letters to Chris McMaster’s agent and then Trevor Bannister’s contract, a music cue sheet, the first page of the shooting script for Episode 1 (as per the previous extra), the programme budget (£1500 per episode). Following this is material from December 1965 for Object Z Returns with a synopsis, and finally a request to publish the scripts in book form in 1973.

Booklet

Included in the first pressing of this release, the BFI’s booklet runs to twenty-eight pages plus covers. Following a spoiler warning, Jon Dear begins with “Children of the Revolution: Object Z and Playing Politics with Kids’ Telly”. Dear places Object Z in a tradition of small-screen genre which had adult leads but didn’t patronise their audience, his example being Ace of Wands and a bridge to shows made for adults but accessible to older children, such as The Avengers and Sapphire and Steel. The other tradition Dear places Object Z in is the disaster movie, prevalent in 1970s cinemas but with earlier examples such as the 1961 The Day The Earth Caught Fire. And this was a story of impending catastrophe made in a TV studio in London. Dear talks about the reaction to the show, with some newspapers indeed wondering if this was really a children’s serial, and some parents complaining it was too scary for their offspring. If in most regions those children stayed to watch the next programme, the news, they would have seen the real-life versions of some of the issues in McMasters’s scripts. He covers the serial’s production and what is known of Object Z Returns. Given the serial’s obscurity, due to its unavailability before now and people’s fading memories, he hopes that this release will be a rediscovery. I’d go along with that.

Dr Elinor Groom is next with “Daphne Shadwell and Object Z”, which concentrates on the life and career of the serial’s director. Shadwell was one of four daughters of Charles Shadwell, who had been musical director of the BBC Variety Orchestra in the 1930s. She began to work at the BBC after secretarial college, as did all her sisters, but she was the only one of them to stay in broadcasting for her whole career. Working in the BBC’s children’s department, she was poached by A-R when it began broadcasting. When A-R closed, she moved to Thames. During the decade, the budgets for children’s programming dwindled and she left the department and worked in current affairs.

After credits listings for all six episodes, William Fowler contributes “The Times They Are A-Changin’: British Science Fiction Television in the 1960s”. This sets Object Z in its context in the mid-Sixties, not just the Bob Dylan song which gives the piece its title, and science fiction in print and on the small screen becoming a way to deal with the current world. In some cases, television protocols became part of the drama, such as the journalist-heroes of Object Z and the documentary stylings of Peter Watkins’s Culloden and The War Game. Fowler discusses Out of the Unknown, mostly adapted from existing SF stories, and children’s shows such as Thunderbirds, which created new worlds and used the new technology of colour to the mix, at least if you were one of the few with access to a colour television set. Dick Fiddy follows with “Associated-Rediffusion”, an overview of the company and the television channel, from its launch to its closure, listing several well-known programmes made by the company in its thirteen years of operation.

The booklet also includes notes on and credits for the extras and plenty of stills.

final thoughts

Object Z

UK 1965 | 147 mins total

directed by: Daphne Shadwell

written by: Christopher McMaster

cast: Margaret Neale, Denys Peek, Ralph Nossek, Trevor Bannister, Brandon Brady

distributor: BFI

release date: 29 September 2025

- For example, the now-lost series R3 and Legend of Death, the existing series Undermind, three Wednesday Plays – Fable, Campaign for One (lost) and The Girl Who Loved Robots (lost) – and the Armchair Theatre A Voice in the Sky. 1965 also saw the continuation of Doctor Who, the launch of Thunderbirds and Out of the Unknown and would have seen the broadcast of Peter Watkins’s The War Game if the BBC hadn’t pulled it. Lyons mentions only British productions, but the first series of the Australian production The Stranger was broadcast by the BBC that same year.[↩]