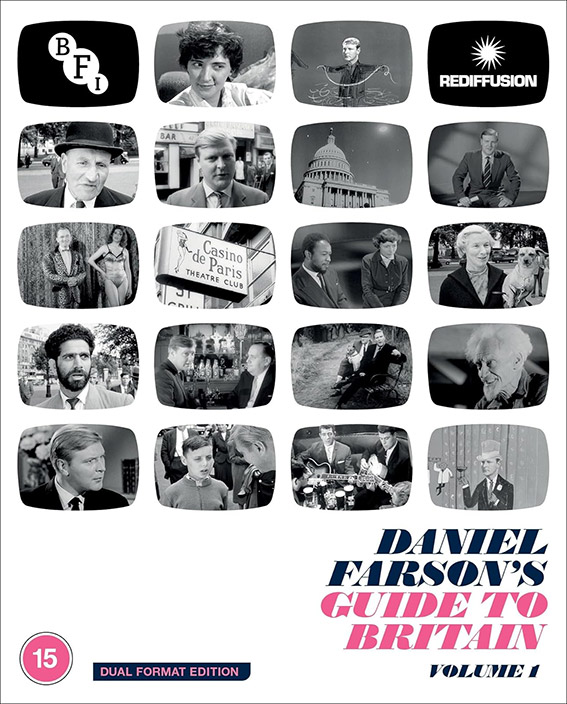

Daniel Farson’s Guide to Britain Volume I

The second of the BFI’s releases from the Associated-Rediffusion catalogue, DANIEL FARSON’S GUIDE TO BRITAIN VOLUME 1 is released as a dual-format edition in which he looks at aspects of life, culture and famous people of the late 1950s to the early 1960s. Gary Couzens opens the time capsule.

Britain gained a second television channel when ITV launched in 1955, at first in the London area with the franchise divided between ATV at weekends and Associated-Rediffusion (later simply Rediffusion) during the week. Some of the great and the good of the day regarded this newcomer, funded by advertising rather than by the licence fee, as a symptom the decline of British culture, but it’s true that ITV, more populist but not unintelligent, did shake things up. Daniel Farson (1927-1997) made his name with a series of interviews and looks at aspects of post-War British culture, good and bad, his style being less deferential than the then rather stuffy BBC. His style was influential on later interviewers and cultural observers, such as Alan Whicker and Louis Theroux.

Farson was born to American journalist Negley Farson (whom he interviewed in Pursuit of Happiness). As a youngster he went to Germany with his father, who was reporting on the rise of Nazism, and he was patted on the head by Hitler, who called him a good Aryan boy, fair hair and all. A gay man at a time when male homosexuality was illegal, during his work as a parliamentary correspondent at the House of Commons, he was pursued by gay Labour MP Tom Driberg. He joined Associated-Rediffusion shortly after its start and began his series of programmes, many of them quarter-hours broadcast late at night (allowing content which wouldn’t have flown pre-watershed then or even now). Outside his broadcasting career he was also an author. He was a relative of Bram Stoker, and wrote a book and made a television programme about him and his most famous creation. After hours a habitué of London’s drinking scene, along with celebrity friends like Francis Bacon

This release collects fourteen of his programmes, broadcast between 1957 and 1963.

OUT OF STEP: WITCHCRAFT

OUT OF STEP: OTHER WORLDS ARE WATCHING US

“Is it wrong to be out of step? Dan Farson goes out to challenge people who hold odd views about life. Are these people just cranks, or are they one step ahead of us?”

Out of Step was a documentary series, which was first broadcast on Associated-Rediffusion in the last quarter of 1957. From TV listings of the time, it wasn’t networked to the other ITV regions, and of the fourteen episodes only six still exist, of which two are on this disc. Each episode, a little over thirteen minutes, was broadcast fairly late on a Wednesday night, at 10.30pm, followed by presumably a commercial break and then the news at the rather precise time of 10.46 pm. Other “odd views” included nudism (which would now be called naturism, the episode including allegedly the first naked woman shown on television, and according to the booklet to be included in Volume 2), Scientology, anarchy, spiritualism, body-building and even couples who have (gasp!) no intention of getting married. Of these, the nudist episode is still in the archives so may turn up on a future volume, and on the evidence of what is on the present disc, you might be surprised at the possibility of reasonably discreet nudity turning up in your living room in the late 1950s. On the evidence of these two episodes, Farson was generally sceptical but does allow his interviewees to have their say.

Witchcraft was the twelfth episode, broadcast on 4 December 1957. Although this is a short programme, like the others in this set it packs a fair amount in. In this instance, as the title suggests, Farson looks at the phenomenon of modern witchcraft. First up is anthropologist Dr Margaret Murray, very lucid at ninety-two years of age, who reckons that a young person might prefer to be a member of a coven than, say, a nudist colony. On to prominent witch (or Wiccan) Dr Gerald Gardner, thickly bearded but frequently impishly smiling. He was the author of Witchcraft Today, published in 1954 after the longstanding Witchcraft Act had been repealed three years earlier. And yes, he is a practising witch, and yes they do perform their ceremonies in the nude. He reckons there are about four hundred witches in the UK at the time of broadcast. Finally, we have Louis Wilkinson, a friend and the executor of Aleister Crowley. The programme doesn’t go so far as to show us any ceremonies, but we do get stock footage of African dancers and also Adolf Hitler (“perhaps the greatest witch of all time”), due to his charismatic presence similar to witches’ use of powers of suggestion.

Other Worlds Are Watching Us was broadcast earlier in the run, the second episode, on 25 September, and here Farson meets people who believe in strange lights in the sky being harbingers of alien races. Some of them have even been abducted. This is illustrated at the start by footage from the 1951 classic SF film The Day The Earth Stood Still. UFOs were a big interest of the time, but Farson is clearly sceptical. So is Sir Harold Spencer Jones, the then Astronomer Royal, who points out that even if the aliens came from the nearest star system to the Solar System, Proxima and Alpha Centauri, they would have to travel four years to get here if they travelled at the speed of lights. Maybe they are Methuselahs, he suggests. Other burning questions are asked, such as what the women on Venus are like.

Mark Pilkington, a writer and publisher with a “longstanding interest in the outer edges of belief”, provides a commentary on both episodes. His one for Witchcraft seems to have been edited together from different takes as there are changes of ambience from time to time. He gives us the background of his interviewees and drops the information that when he interviewed Gerald Gardner he had been out drinking the night before and had been involved in a fight, resulting in a black eye. So his close-ups and reaction shots had to be filmed about a week later. On Other Worlds Are Watching Us, he suggests that the episode might have been inspired by the book Is Another World Watching? by Gerald Heard, who suggests that giant bees might alone survive the G-forces experienced by UFOs. He spends much of the running time discussing the thoughts and fears of people from another world, and the links between believers and the hippies of the next decade. There are some gaps even in a programme which runs just over thirteen minutes. He does undermine Spencer Jones, by pointing out that he doesn’t always get it right, poo-pooing space travel just before it happened.

KEEPING IN STEP: THE WEDDING

KEEPING IN STEP: STOCK EXCHANGE

“Each week, Dan Farson meets a conventional point of view.”

Keeping in Step followed Out of Step in quick succession, beginning just two weeks later on New Year’s Day 1958. Again it was in a fifteen-minute slot, this time starting a little earlier, at 10pm, though later episodes moved back to 10.30. This was a shorter series: six weekly episodes on Wednesdays up to 12 February, then after a three-week hiatus three more from 5 March. This series has a better survival rate. There is just one episode missing, so we can’t see behind the scenes of the late-Fifties Women’s Institute. So instead of those living outside society’s norms, Farson meets those who very much live within them.

The Wedding (22 January) begins with Farson in a three-piece suit and top hat, walking up to camera and saying, “I may look like a complete muggins. I certainly feel one, but part of this is doing the right thing.” That right thing is the wedding. We all have ceremonies when we are born and when we die, but for those who tie the knot (who wouldn’t have featured in one of the Out of Step episodes) this is one in between. The three most exciting words we might hear, Farson suggests, are “I love you” and the most expensive, “Will you marry me?” Yours for as much as five and a half guineas. A happy couple is interviewed, and they say that they went for a white wedding to please their families. A best man gives a speech: the wedding is eighty percent the bride’s day but the bill is a hundred percent the man’s.

On to The Stock Exchange, broadcast on 12 March. Farson is in a suit and tie, but even so feels out of place amongst all the men (and they are all men) on the stock exchange floor, earning at least £500 a year, which could have bought you a house in 1958. Many of them came from public schools. As actual dealings were confidential, Farson and a couple of brokers recreate one using a fictional company called Nosraf (Farson backwards). You have to wonder how much this was aspirational material at the time, a likely career path for those from the right backgrounds, and possibly an expected one for many given that it part of a series called Keeping in Step.

THIS WEEK: SOHO STRIPTEASE

THIS WEEK: ROBERT GRAVES [PRODUCTION MATERIAL]

This Week was a half-hour magazine programme, which unlike the two series above, was not only made by Associated-Rediffusion but networked across the then five ITV regions, at 9.30pm on Thursdays. Soho Striptease was an item from the edition of 24 April 1958, which explains its shorter length, just over half that of the Out of Step and Keeping in Step episodes. (Soho Striptease is, as far as I’ve been able to ascertain, not related to the film of the same name which the BBFC rejected for cinema viewing in 1959.) 9.30pm is still after the watershed though, so given the subject matter, we do get some brief nudity, topless, in longish shot, with nipple pasties providing a little modesty. Given that swathes of television from the late 1950s no longer exist (anything not prefilmed, like this, was broadcast live) you have to wonder how much of the viewing public was used to becoming hot under their collar in their front room. Farson interviews some of the strippers, who seem quite clear-eyed about their profession, on an afternoon at the Panama Club on London’s Great Windmill Street. Some of them have boyfriends. Farson spends his time at the bar, which given that he was a well-known drinker and was gay, may have been a more appealing prospect for him.

Commentary duties on Soho Striptease are given to Vic Pratt who, given that he has only six and a half minutes to play with, concentrates on the legal issues of on-stage nudity. The law had changed and no longer was nudity only allowed if the women did not move.

Next up is an interview with novelist and poet Robert Graves, shot in 1957. He was best known then as a poet, autobiographer (his account of his World War One service, Goodbye to All That) and his two novels about the Roman Emperor Claudius, the basis of the classic TV series I, Claudius from 1976, first broadcast while he was still alive. (He died in 1985 at the age of ninety, and the series was repeated that year as a tribute.) For whatever reason, this interview was never broadcast and it survives as unedited production material. So we have leader running through, on-screen clapper boards, and a few retakes, a woman’s voice on the soundtrack prompting Farson, then at the end shots of Farson asking his questions and a few reactions. Graves, about sixty-two at the time and living in Majorca, has a rather above-it-all air to his answers, considering that as a writer he is one of a dying breed. There isn’t much being published he finds readable. You have to wonder what he thought of the novelists among the Angry Young Men – and a couple of women, including one who will be along in a while – coming to prominence at the time. The reduction of talks on the BBC on literature and the arts comes over like the barbarians at the gates for him.

PEOPLE IN TROUBLE: MIXED MARRIAGES

“Most people have problems and troubles. Some people have more than their share. In this series, Daniel Farson goes out to meet them.”

People in Trouble was another series in fifteen-minute time slots, broadcast at various post-watershed times and not networked. It had quite a long run of twenty-one episodes, of which five are missing. Mixed Marriages was the second, broadcast on Wednesday 21 May at 10.45pm (not 10.30 as the booklet says, according to TV listings of the time, but the time slot did vary week by week). Here, Farson discusses the phenomenon of mixed marriages in the racial sense.

Trigger warning: in this episode, the “language and attitudes of the time” klaxon goes off very loudly indeed. You can expect outdated terms like the “colour bar” and “coloured” (which features on some other episodes in this set). Farson mentions that there are 190,000 coloured people in the country and wonders if the colour bar is beginning to fade or not. Racist attitudes are very much discussed, and representing them we have the jaw-dropping contribution of James Wentworth Day, then fifty-nine years old, unsuccessful Conservative Party candidate at two elections, and an admirer of Mussolini. Apparently he was a bit suspicious of Hitler, though. He seems to have been Farson’s pet reactionary, as he also appeared in an episode on transvestism advocating the hanging of gay men. (Farson may well have taken that personally.) So words like “half-caste” and “mongrel” are thrown about, as well as suggestions that people of colour are little better than cannibals and often mentally deficient. Farson doesn’t challenge him but does make it clear that he couldn’t disagree with him more. Given the activities of the Far Right as I write this, we shouldn’t be so complacent that we have moved on since 1958, though interracial couples hardly raise an eyebrow nowadays. But even today’s racists don’t display their racism as nakedly as this.

After that, it’s a relief to meet one and a half interracial couples, in both cases Black man and white woman, never the other way round. The couple we see seem happily married, but the single woman we next meet most definitely wasn’t and is now single again. She blames the failure of her marriage on her husband’s patriarchal attitudes from his cultural background. And, to balance out Wentworth Day, Lord Altrincham, who is supportive. He had been blacklisted by the BBC at the time for comments made about Queen Elizabeth II.

The commentary is the work of Chantelle Boyea and Milo Holmes, who tackle the episode from a racial perspective. They fill in some of the background to the episode, pointing out that it was broadcast three months before the Notting Hill riots. They talk about other representations of interracial relationships on screen, which went back as far as the 1951 film Pool of London and as up to date as Steve McQueen’s 2024 film Blitz.

SUCCESS STORY: SHELAGH DELANEY

SUCCESS STORY: MAURICE WOODRUFF

THIS WEEK: ROBERT GRAVES [PRODUCTION MATERIAL]

“Why do some people get to the top? Does success mean happiness? In this series, Daniel Farson examines the curious ingredients of success. Each week, he interviews a new personality.”

Success Story was another series of fifteen-minuters, broadcast on Monday nights at 10.45pm. That made it the last programme of the night, other than the weather forecast and the epilogue by some churchman or other which were training grounds for future directors like John Boorman and Alan Clarke. It ran for twelve episodes, a batch of seven from 5 January 1959, then after a week’s break another five. I haven’t been able to determine how many survive, but he we have three for our delectation. As with other series, it wasn’t networked across what had then become six ITV regions.

First up is Shelagh Delaney (9 February), just twenty years old, and a success due to the stage production of A Taste of Honey at the Theatre Royal, Stratford East. The day after this was broadcast, the play transferred to the Wyndham Theatre in the West End. Film rights had been sold for £20,000, and that film was to come out in 1961 to become an important part of the British cinematic new wave, as it had been in its theatrical version. News coverage emphasised not only Delaney’s youth and her working-class Northern credentials (born in Salford, the daughter of a bus inspector) but also her height. Kenneth Tynan said she was “over six feet tall”, but she was actually 5’11”, and you can see her as a vertically-unchallenged woman watching a netball match near the start of the film. This episode begins with an extract from a stage production of the play.

Farson’s interview is remarkably casual, with both he and Delaney sitting on the floor, her back to an armchair. The fire is on and she plays with her dog while she and Farson chat. Farson clearly likes her. Inevitably the money she has made has changed her life and with some youthful confidence she does burn a few bridges with people then still alive. She repeats the story that the play came about because she saw a Terence Rattigan play and thought she could do better, particularly in the way that Rattigan (a closeted homosexual) depicted gay men. So she did, not having written a play before. Joan Littlewood accepted it for her Theatre Workshop, and the rest was history. She also has a few uncomplimentary things to say about John Osborne’s Look Back in Anger, which she thinks was “bloody awful”. That was however the play which kickstarted the Angry Young Men movement in novels and on stage, and later on film, of which she and Ann Jellicoe (The Knack) were the two distaff members. In hindsight, her star was to rise and possibly peak with the release of the film, of which she co-wrote the screenplay. She had some other notable scripts in her (Charlie Bubbles, Dance with a Stranger) but she would never replicate her stage success.

Dick Fiddy’s commentary begins with a general discussion of Farson’s style, techniques and his strengths. He and Delaney seem very comfortable in each other’s presence and he’s impressed by how much he gets out of her, even if they do come from different worlds. Fiddy talks about how different Farson’s style was to those at the BBC, and how they modernised their outlook in reaction. He does make one slip, though, calling Joan Littlewood Joan Greenwood. Like Farson, Fiddy also likes Delaney, saying that she comes over as someone he’d like to go to a pint with. He finishes by wondering what Farson would have done if he’d continued in television, maybe becoming a chat-show host.

After that, we have Maurice Woodruff, broadcast on 30 March. Maurice was a clairvoyant (not, he is keen to emphasise, a fortune teller) with a wealthy and influential clientele. Instead of approaching his subject directly, as Farson did with Delaney, here he begins by talking to two of Woodruff’s celebrity customers. First is Peter Sellers, interviewed in costume as Fred Kite for the then-in-production I’m All Right Jack, who bears out his own observation that there was no “there” there for him, and without his costumes and funny voices he didn’t exist. Sellers claims that Woodruff told him that someone with the initials MZ would be significant, and he would play multiple roles – and indeed he did with The Naked Truth (1957), directed by Mario Zampi.

Following that, Farson speaks to Diane Cilento, who expresses curiosity about the process, and seems to be seeking reassurance. Then it’s on to Woodruff himself, filmed at his well-heeled London home. Woodruff says that many of his clients do indeed like to be reassured but he will tell bad news if necessary. Ultimately, his clients are looking to have problems resolved as much as he can. He believes he has a 75/25 success rate. He also has a look at what the future might hold for Farson.

The commentary is by William Fowler and Vic Pratt, who clearly find both Sellers and Woodruff distinctly fishy. They tell anecdotes of Sellers doing a screen test for the Boulting Brothers, after which the crew applauded – clearly an example of the reassurance the man needed. Woodruff also told him that the letters BE would be significant – not just Blake Edwards, who directed The Pink Panther and many of its sequels, but also Britt Ekland, whom Sellers went on to marry. Although it’s not stated in the programme, but Woodruff was gay. Did he and Farson move in similar circles?

Hank Janson is next (8 July, according to the version of the booklet supplied, but TV listings don’t bear that out). He was a prolific writer of hardboiled crime novels, yours in cheap (two shillings and sixpence) paperbacks, one a month, not all written by one man, real name Stephen Frances. Again, Farson approaches him indirectly, first talking to his publisher, Reg Carter, who says he has never read one of Janson’s novels, despite going to prison on his behalf by losing an obscenity lawsuit. (He spent four months behind bars, being let out for good behaviour.) And now we head over to a strip club, again the Panama Club in Piccadilly (more discreet topless nudity here), for a bizarre interview for which Janson turns up in a heavy overcoat and hat, with a face mask to protect his identity. Janson doesn’t think any book should be obscene (this was before the trial of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, remember). He talks about his writing process, which involved dictating his work in the main, originally on wax cylinders. Farson asks him to describe the venue in the style of one of his novels, including the blonde woman sitting at the bar nearby. Janson plays up to type, when he leaves patting her on the flank and calling her “Coffee Rocks”.

Vic Pratt’s commentary lasts just eight minutes, two thirds of the running time. He does cover a lot of bases though, such as Janson’s real identity, some of his other pseudonyms, and the fact that Janson was also the name of the central character, beginning with When Dames Get Tough in 1948. Pratt’s first encounter with Janson, who died in 1989 (age and birthdate unknown), was seeing a copy of one of his novels in a junk shop. Several of them are still in print.

PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS: PEOPLE APART

“If you feel exhausted by the complexities of present-day life, where can you go to get away, not only from your normal surroundings but also possibly from yourself?”

Pursuit of Happiness was another series of quarter-hours, broadcast on Thursdays from 26 May 1960 for five weeks at 10.45pm, then another eight from 15 September at the earlier time of 6.45pm, so introducing Farson to younger audiences. This time the series was networked, though not every region simultaneously. Again I don’t have information on its survival rate, but this episode represents the show on this release.

People Apart was the fourth episode, broadcast on 16 June. Here, Farson travels to the island of Lundy, off the Devon coast in the Bristol Channel and the people who have gone to live there. The island has a shop, which sells distinctive puffin stamps for its postcards, a hotel and a church, the dream of the appropriately named Parson Heaven. Getting away from it all involves cutting yourself off from the rest of the world for some of the islanders, one of whom never reads newspapers except for maybe the cricket in the summer.

On commentary duties is Dr Elinor Groom, or Ellie Groom as she introduces herself. She finds the film “beautiful” (I suspect many people would have loved for it to be in colour) and fills in some background details. Lundy was relatively local for Farson, as his parents lived in Devon. Indeed, elsewhere in the series, Farson interviewed his own father, Negley Farson. The then owner of the island, Albion Harman, who is interviewed, died in 1969 and the island is now owned by the Landmark Trust. Groom also says that Parson Heaven’s church, which the documentary says was likely to fall down within two decades due to the wrong lime cementing the granite blocks, is still standing, and the post office still sells puffin stamps.

CELEBRITY: CLIFF RICHARD

Celebrity was broadcast at first at Farson’s usual time slot, at 10.45pm on Wednesday nights, beginning on 12 August 1959 and later moving to 6.10pm. That was a good move, given the youthful appeal of this week’s subject, Cliff Richard, broadcast on 30 September at the earlier time. In this case, the whole series survives, so hopefully another example or two could be included in a future Farson set.

At this juncture, Richard was two months away from his nineteenth birthday, and in the previous year had had his first hit, “Move It”, which reached number two in the charts. By now he had sold two million records and received over a thousand fan letters a day. He had been born in India and Farson quizzes him on this: he finds Britain more stuffy than he did India, and London was several years away from beginning to swing. He left school at sixteen and a half, with not many qualifications (he passed English) but pop stardom soon beckoned. Born Harry Webb, he changed his name at the suggestion of his manager. He says he earns under £1000 a year, but that was a considerable sum then, and he was able to buy his mother a house. He also bought a car which he is learning to drive. With hindsight, given how his career progressed, he says some revealing things. He isn’t rebellious, and the young rock-and-roller was to become the mainstream entertainer of later years. Given his avowed celibacy, it’s also revealing that he doesn’t have a girlfriend because, he says, because that would be unfair on her. He is looking to develop his acting skills, possibly in roles where he doesn’t sing.

FARSON’S GUIDE TO THE BRITISH: CATS

“Daniel Farson takes a new and unconventional look at the British, with a kindly eye.”

With this series, Farson finally had his name in the title, a run of thirty quarter-hours, also broadcast towards the end of the day’s schedule on Thursdays in 1959, at 10.45pm. The theme tune was performed by Russ Conway, no less, a pianist who that year had had two number one hit singles. Sadly, only one episode survives, this one, broadcast on 3 December. After a brief overview of cats in history, Farson tackles the British love of Felis domesticus. So we meet the Dowager Lady Aberconway, author of A Dictionary of Cats, who takes in strays and advertises for their new homes in The Timesand Daily Telegraph. She does advocate neutering to reduce the stray population. Another cat owner feeds her charges on pheasant. At the other end of the scale, Farson meets a pair of taxidermist, those to ensure your feline friend lives on after its passing. There are plenty of cat close-ups to maintain your cuteness threshold.

On the commentary track, Dr Groom returns, here paired with Lisa Kerrigan. They point out the subject matter has dictated an all-female set of interviewees, with the exception of the taxidermists. As the rest of the series is missing, they give us a runthrough of what we might have seen back in 1959 had we been watching: a look at tourists in Britain, gardens, boxing, musicals, a tour of Blackpool and, a little darker, British murderers and ghosts. Cats was Farson’s hundredth interview programme and they cite Peter Black in the Daily Mail, who alleged that Farson didn’t actually like the little beasts.

BEAT CITY

We move forward to 1963, the year, as per Philip Larkin, that sexual intercourse began, if a little late for him, before the Beatles released their first LP. In this programme, a standalone piece not part of a series (broadcast on Christmas Eve at 9.10pm), Farson travels north to the Fab Four’s home city of Liverpool and looks at the music scene there. This is rather longer than other Farson programmes, long enough to include a commercial break in it, with End of Part One/Part Two captions on screen. Other than the opening blast of “There’s a Place”, The Beatles don’t actually feature in this show, which shows us footage of many of the other bands around at the time, many of them long forgotten now. Most of the performances in the first part are at the Cavern Club, including Faron and the Flamingos (“Do You Love Me”, which became a hit for Brian Poole and the Tremeloes) and fifteen-year-old Chick Graham who blasts out “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow?” (a Carole King/Gerry Goffin composition and on the face of it, maybe an odd one for a male to sing). In Part Two, Farson ventures out wider in the city, including an acoustic-guitar duo performing in a pub, which could have been an outtake from a Terence Davies film if he hadn’t made clear (see his Liverpool documentary Of Time and the City) that this music was very much not his cup of tea. Farson and his crew keep the big guns near to the end, with several numbers from one of the biggest bands in Liverpool at the time, Gerry and the Pacemakers, answer to the well-known trivia question as to who was the first act to have their first three singles go to number one. (We hear two of them, “I Like It” and “You’ll Never Walk Alone”.) As a time capsule for fans of the music of the time, this is essential.

Commentary duties again go to the pair of William Fowler and Vic Pratt. Pratt, in particular, is in his element, dropping a “gear” and a “groovy” along the way. He also makes recommendations of the best versions of some of the songs we hear, so off to a certain video file-sharing service you go. They talk about how Farson carefully appeals to young and old, given the youthful subject matter, for example his opening conversation with an elderly couple in a cemetery. In between the various acts, we have actuality footage of young Liverpudlians, Black and Asian faces among them, showing how much of a melting pot the city was. They compare this with the BBC documentary Morning in the Streets from 1959, and we see some no doubt Catholic graffiti saying “King Billy is a Basted [sic]”, a jab at William of Orange who had overthrown James II and had become William III. They point out that, like Hamburg where the Beatles established their reputation, Liverpool is a port city and a lot of the music influencing this scene came in from America via ship. As for The Beatles’ absence (that opening song apart, and Farson name-dropping that he chatted to Paul and Ringo in a bar), that has a history. The programme’s director Charlie Squires wanted to include them, but couldn’t come to an agreement with their manager Brian Epstein, who wanted to showcase another of his acts, Cilla Black, a cloakroom attendant at the Cavern before her singing career, whom he had only recently signed and whose debut single (“Love of the Loved”) hadn’t been especially successful. In retrospect this seems a major omission, but you have to wonder if anyone knew how successful the Beatles would be, or if they would last, and so we have Gerry and the Pacemakers instead。

sound and vision

Daniel Farson’s Guide to Britain Volume 1 is a dual-format (one Blu-ray, two DVDs) release from the BFI. This review is based on the Blu-ray disc, which is encoded for Region B. The DVDs have not been seen, but they will be encoded for Region 2 only. While the BFI has released from the Rediffusion catalogue before (such as the 2018 releases of At Last the 1948 Show and Do Not Adjust Your Set) and at least one of the films in this set has appeared on a previous release as an extra (Witchcraft on the Flipside release of Legend of the Witches and Secret Rites), this is the second formally-labelled release from the catalogue, following Object Z. As the disc starts, an Associated-Rediffusion Presents ident plays.

Documentaries like this could be exempted from BBFC classification if they contain nothing which would be rated other than U or PG. This set carries a 15 certificate, though the reasons are not on the BBFC database as I write this. Candidates certainly include some very racist comments on Mixed Marriage and what would now be called sexualised nudity (striptease) on Soho Striptease, naturally, and Hank Janson. Past BFI releases have sometimes included content advisories that play before the film or programme starts, but there aren’t any here, not even on Mixed Marriages which amply deserves one.

The films were shot on black and white 35mm film, which is no doubt a reason why so many have survived, as in the late 1950s, a lot of television was live over 405 lines. The transfers were at 2K resolution from original elements and are presented in the original ratio of 1.33:1. As these were made for British television, they were shot at twenty-five frames per second as that was television speed (or, to be precise, fifty frames per second) and the transfers are at that correct frame rate. There is some minor damage but it’s all very watchable, especially when viewed on larger and less forgiving equipment than the “high definition” 405-line sets of the day. Cats, which according to the commentary exists as a 16mm telerecording, is distinctly softer than the other transfers. Beat City, provenance unknown to me, looks fairly soft too.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 2.0, and little needs to be said. It’s clear and well-balanced, even being listened to via speakers much less forgiving than the television speakers of their day. English hard-of-hearing subtitles are available, and I didn’t spot any errors in them.

special features

Commentaries

Ten of the fourteen items have commentaries provided, from many of the regular names on BFI releases. For neatness’s sake I have described them above following each relevant episode, but for the record they are: Mark Pilkington on Witchcraft and Other Worlds Are Watching Us, Vic Pratt on Soho Striptease and Hank Janson, Chantelle Boyea and Milo Holmes on Mixed Marriages, Dick Fiddy on Shelagh Delaney, Pratt and William Fowler on Maurice Woodruff and Beat City, Dr Elinor Groom on People Apart and Groom and Lisa Kerrigan on Cats.

Beat City image gallery (2:07)

A self-navigating gallery of stills, all of them in black and white, some of them featuring Farson with the bands.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing only of this release, runs to twenty-eight pages plus covers. It begins with “Daniel Farson: In Step” by William Fowler. This is an overview of Farson’s life and career. By the end of the 1950s he was famous to the extent of being mobbed in the street, inundated with fan mail and by then the object of parody, as Monty Python would do to Alan Whicker more than a decade later. One woman wrote to TV Times to ask for more information about “the most handsome man on television”. His programmes, shot on film, were, Farson claimed, inspired by cinema vérité and the then-current French New Wave, though that’s not so obvious nearly seventy years later. Farson began in print journalism, but his work for Associated-Rediffusion introduced the London viewing public to subjects they may not have encountered, not even in newspapers in some cases. Britain was reeling from the Suez Crisis and London was still largely scarred by wartime bomb damage, something we see with the strays’ wanderings in Cats. Fowler also interviewed many people famous at the time, showing them as human beings, if sometimes quite eccentric ones, but remained an observer, though not always a neutral one.

After this, we have credits for on the individual episodes, with short notes by William Fowler (Witchcraft), Milo Holmes (Mixed Marriages), and all others by Vic Pratt. Lisa Kerrigan contributes “Success Story: Daniel Farson and Associated-Rediffusion”, which covers the establishment of the channel, recruiting people from the cinema and the theatre, and others who had answered advertisements and were new to the medium, to combat the one other channel of the day. Some of them did indeed jump ship from the BBC. One was Caryl Doncaster, who started This Week in 1956 and so provided Farson with his first outlet on the small screen, a rival to Panorama on the other side, beginning later that year. Farson’s later documentaries, often broadcast late and night, contrasted with the comedies and game shows on earlier in the evening. Some of Farson’s work featured in the first ever television retrospective at the then National Film Theatre in 1957.

“George Haslam: Designing Television’s New Age” is a short piece by filmmaker Nic Wassell, the subject’s grandson. He designed among other things, Associated-Rediffusion’s “astral” logo, which you can see in several places on this release. He was a long-standing designer at the channel, believing that design had to be different to that on the big screen or the stage. A fond if brief memoir. The booklet also includes plenty of stills.

final thoughts

While many aspects of these episodes have obviously dated, they, or rather the examples included here, remain entertaining and illustrative of the times that produced them. Sometimes that’s uncomfortably so, and you may be surprised of what could sometimes be allowed on the little box in the corner before the 1960s, before Mary Whitehouse began her activities. This is Volume 1, and there’s no doubt plenty to be going on with for future volumes.

Daniel Farson’s Guide to Britain Volume I

Out of Step: Witchcraft

UK 1957 | 13 mins

directed by: Geoffrey Hughes

written by: Daniel Farson, Stanley Craig

presented by: Daniel Farson

speaking to: Dr Margaret Murray, Dr Gerald Gardner, Louis Wilkinson

Out of Step: Other Worlds Are Watching Us

UK 1957 | 13 mins

directed by: Elkan Allan

research: Stanley Craig

presented by: Daniel Farson

speaking to: Hon Brinsley Le Poer Trench, Gavin Gibbons, Dr Percy Wilkins, George King, Sir Harold Spencer Jones

Keeping in Step: The Wedding

UK 1958 | 14 mins

directed by: Rollo Gamble

written by: Stanley Craig, Daniel Farson

presented by: Daniel Farson

speaking to: D Canon Hayman, Mr and Mrs Silk, Mr and Mrs Smith, Mr and Mrs Lowen, Mr Leonard Shaw

Keeping in Step: The Stock Exchange

UK 1958 | 13 mins

directed by: Rollo Gamble

written by: Daniel Farson

presented by: Daniel Farson

This Week: Soho Striptease

UK 1958 | 7 mins

introduced by: Ludovic Kennedy

featuring: Daniel Farson

This Week: Robert Graves (Production Material)

UK 1958 | 20 mins

featuring: Daniel Farson, Robert Graves

People in Trouble: Mixed Marriages

UK 1958 | 14 mins

directed by: Rollo Gamble

written by: Stanley Craig, Nickola Sterne

presented by: Daniel Farson

Success Story: Shelagh Delaney

UK 1959 | 13 mins

directed by: Rollo Gamble

written by: Daniel Farson

presented by: Daniel Farson

featuring: Shelagh Delaney

Success Story: Maurice Woodruff

UK 1959 | 13 mins

directed by: Rollo Gamble

written by: Daniel Farson

presented by: Daniel Farson

featuring: Peter Sellers, Diane Cilento, Maurice Woodruff

Success Story: Hank Janson

UK 1959 | 13 mins

directed by: Rollo Gamble

written by: Daniel Farson

presented by: Daniel Farson

featuring: Hank Janson

Pursuit of Happiness: People Apart

UK 1960 | 14 mins

directed by: John Frankau

written by: Rosemary Davies

presented by: Daniel Farson

Farson’s Guide to the British: Cats

UK 1959 | 14 mins

directed by: Sheila Gregg

written by: Jacquemine Charrott-Lodwidge, Rosemary Davies

presented by: Daniel Farson

Celebrity: Cliff Richard

UK 1959 | 15 mins

directed by: Geoffrey Hughes

presented by: Daniel Farson

featuring: Cliff Richard

Beat City

UK 1963 | 15 mins

directed by: Charlie Squires

written by: Daniel Farson

presented by: Daniel Farson

featuring: Gerry and the Pacemakers, Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, Faron’s Flamingos, Earl Preston and the TTs, The Chants, Chick Graham and the Coasters, The Spinners, Jacqueline McDonald, Bridie O’Donnell, Billy Kielty and Paul Cunningham

distributor: BFI

release date: 16 February 2026