Charge of the night brigade

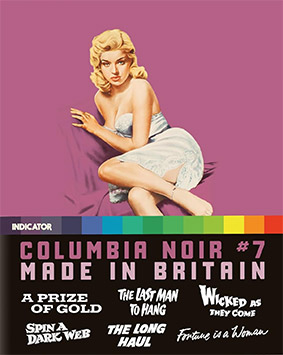

After a couple of months away from the review desk due to difficult personal circumstances, Slarek gets to grips with the six British noir titles and the many hours of special features that make up Indicator’s splendid Blu-ray box set, COLUMBIA NOIR #7: MADE IN BRITAIN.

What was I thinking? After a personal issue-enforced period of non-reviewing and far too long spent on my end of year piece, what did I choose to restart my disc reviewing with? A six-film box set with over 20 hours of special features. If Cine Outsider was a YouTube channel, this is where I would let out the sort of sigh made by Kiff when Zapp Brannigan says something idiotic in Futurama. My reasoning for picking this set was straightforward enough, at least in my jumbled mind. Gary’s recent additions to his usual BFI review slate and SilverBlueSnow’s capsule review of Girl With a Suitcase were all Radiance titles, and keen though I am to get to grips with more of that distributor’s discs myself, I strongly felt it was time we covered another release from Indicator, whose Blu-ray titles have of late been criminally neglected by this site. And we do love Indicator and would ideally like to cover every disc they put out. So, I wondered as I sorted through my review discs, what was the most recent release there from that label? Why, the latest box set in its collections of films gathered under the Columbia Noir umbrella. And these ones were all examples of British-made Noir. Woah, count me in! As ever, I seriously underestimated the scale of the task and the disruption to the process that real life can cause. Once again, my daytime job then got in the way, as did a seemingly alarming new development of an old health issue that at one point looked set to take me out of the loop for a while in the near future, though for now, at least, the urgency has thankfully lessened.

So, what about the discs? Well, I’m not sure what I was expecting from this set, having not once thought of film noir as a particularly British genre, but just as rap crossed the Atlantic and seemed to fit the French language like a musical glove, there’s no reason at all why noir shouldn’t equally feel at home in the dark alleyways of London, Manchester, Glasgow or Liverpool. Of course, as noted in the special features, precisely specifying what qualifies as noir is a tricky call and open to subjective interpretation, which is certainly relevant to the six titles that make up this collection. For my money they range from noir light to fully fledged noir tales that justify comparison with their Hollywood counterparts. Five are in black-and-white but the first is in colour, and that’s one that for me doesn’t really earn its noir classification until late in its genre-switching story. All six films were released between 1955 and 1957 and all began life as published novels, two were directed by Ken Hughes, three have the male lead played by American or Canadian actors, and two feature American actress Arlene Dahl in the lead female role. Patrick Allen, who plays a key supporting role in one film has an almost wordless small part in another, and character actor Sam Kydd has small roles in three, two of them uncredited bit parts.

As is my way, instead of writing one overall review after watching all six films, I elected to watch and write about each of them in their listed (and presumably chronological) order, and while are all of real interest, especially to fans of British crime cinema, for me the collection just gets better as it goes along, peaking with the final two films in this set. Feel free to disagree and make your own ranking. Right, to the films.

A PRIZE OF GOLD

Given the title of this box set, the one thing that’s initially conspicuous by its absence from this first film in the collection is any real hint of noir. That’s certainly true of the opening titles, which unfold in glorious colour as Joan Regan croons the title song, a sequence that feels more like the intro to a Hollywood musical. There’s a degree of intrigue to the scene that follows, as a German crew dredging a river in post-war Berlin unexpectedly uncovers a large consignment of gold ingots that was presumably dumped or lost by the Nazis in the later stages of WWII. The works boss immediately contacts the occupying authorities, and a team of British officers arrive to inspect the find and inform the Americans of the discovery. The two allied forces combine their efforts to retrieve and catalogue the gold, and plans are made to have it shipped to London, a process that will require several journeys by cargo plane.

It’s here that we meet American Air Force sergeant Joe Lawrence (Richard Widmark) and Scottish Army sergeant Roger Morris (George Cole), and the film transforms into a light-hearted buddy movie. Both men are given papers to deliver to their respective commanders and set off to do just that in Joe’s jeep, then get sidetracked when Joe pauses their journey to show Roger how much better his digs are than those of his British counterpart. While the two are in Joe’s pad, the jeep is stolen by a young scallywag named Conrad (Andrew Ray), and with the aid of a helpful lorry river, the two soldiers give immediate chase. The boy eventually runs the jeep into a ditch, and while Roger inspects the damage, Joe chases after the kid and ends up at a makeshift orphanage for children who have lost their parents in the war, one run by the kindly Dr. Zachmann (Karel Stepanek) and the pretty Maria (Mai Zetterling). Roger reveals that the jeep has a broken axle and the two thus have to complete their journey on foot, but it’s clear that Joe has taken a shine to Maria.

The whole escapade lands Joe in trouble with his immediate superior, Major Bracken (Alan Gifford), but he worms out of punishment by effectively blackmailing Bracken with what he knows about his infidelity. When Roger is assigned to accompany the first shipment of gold to the UK, Joe visits Maria and tells her a whopper about needing her personal details for a report on the accident, which he uses to make sure that she is single before attempting to woo her. The previously light-hearted buddy film then shifts gear to become a full-blown romantic drama, complete with an orchestral score by Malcolm Arnold that builds to an explosive crescendo every time Jim and Maria kiss. As I wince a bit at this slice of Hollywood-style overstatement, I’m still wondering when the film will do something to qualify as noir, particularly when this lightning romance takes a whimsical turn by having Joe drive Maria around in a rented Messerschmitt KR200 three-wheeled bubble car to the sort of jaunty music that confirms the vehicle was selected for comic effect.

The first indication of the possible noir to come occurs when Roger returns to Berlin with a cashmere sweater for Joe to give to his new girlfriend and wants to have a chat about a moneymaking proposal that requires Joe’s assistance, but Joe has a date with Maria that he’s not interested in breaking or delaying for anything. By now, Joe has had his first brush with a large and sullen German businessman named Hans Fischer (Eric Pohlmann), who warns him to stay away from the orphanage and appears to exert some control over Maria. When Joe later returns to the orphanage regardless and sees Fischer manhandling Maria against her will, he attacks him and aggressively ejects him from the building. The distressed Maria reveals that she was reliant on Fischer’s patronage for the funds required to transport the children to a new home in Brazil, and after sincerely assuring her that he’ll find some way to fix it, Joe approaches George to discuss his plan to steal the final shipment of gold, and if you think that statement counts as a spoiler then you really need to see more crime and heist movies. Having said that, there will be a couple of genuine spoilers in ahead, so I’d skip the following two paragraphs if you want to avoid them.

For much of its run time I remained in two minds about A Prize of Gold. I liked the friendly partnership that develops between Joe and Roger, much of which you can put down to likeable performances from Widmark and Cole and the chemistry between them. I was less keen on the romance between Joe and Maria, which plays to Hollywood convention in the overstated presentation of the emotions of its leads and the unlikely speed with which their relationship moves from “oh, she’s pretty” to “I’m willing to wreck my career and become a fugitive criminal in order to help her realise her dream.” Once the planning and execution of the heist get under way, the film should by rights be completely in my wheelhouse, but for me there was just one small problem, and that’s that the plan felt doomed to failure from the moment it was conceived. Sure, the censorship of the day included the stipulation that screen crooks should not get away with their crimes, but there really is an overpowering sense from the start here that Joe and George are on a hiding to nothing.

My conviction on this score intensified further when the two men fly to London to recruit additional members to the team, and Roger’s slightly doddery old Uncle Dan (Joseph Tomelty) is given the job of meeting the plane with a truck. This guy? Are you sure? He then introduces them to Alfie Stratton (Donald Wolfit), a former fence now living in comfortable retirement, and while he is ultimately persuaded to shift the gold for them, he wants no direct involvement in the operation. Red flags aplenty are raised when Alfie puts them in touch with former pilot turned pub darts grifter Brian Hammell (Nigel Patrick), a smugly self-satisfied upper middle-class git who you just know is going to do something thoughtlessly selfish that will bugger things up for the rest of the crew. For me, all this stripped the subsequent operation of any real tension, despite – or in some ways, because of – former Val Lewton editor and director Mark Robson and screenwriters Robert Buckner and John Paxton (from the novel of the same name by Max Catto) throwing every potential calamity they could at the plan’s execution. Having said that, this overriding sense of impending failure and personal calamity does buy the film its first slice of noir credibility, but it’s once the crew land in the UK with the hijacked bullion that it really starts to earn its genre stripes, as distrust, regret, betrayal, sacrifice and redemption collide in more effectively tense and involving fashion.

My personal gripes aside, there is still much of interest in the only colour film in this otherwise staunchly monochrome collection. As well as lending the film an interesting setting, the Berlin location work is also of historical interest, being filmed just ten years after the end of the war when shell damaged buildings and bullet hole peppered walls were still part of the landscape, and I’ve little doubt that the sight of the Messerschmitt bubble car will raise the eyebrows of younger viewers. Overblown romantic elements aside, the film is solidly crafted and boasts a uniformly good cast, and while it does have the feel of a Widmark vehicle, he’s on fine enough form for that not to be an issue. I also can’t be the only one who’d happily watch another couple of movies in which he and George Cole play transatlantic buddies.

THE LAST MAN TO HANG

The second film in the set gets off to a sinister start, as middle-aged housekeeper Mrs. Tucker (Freda Jackson) enters the bedroom of her mistress, Daphne Strood (Elizabeth Sellars), and is unable to wake her. She urgently calls for an ambulance and claims that her mistress has been poisoned, and once at the hospital she frantically assures Detective Sergeant Horne (Martin Boddey) that “he murdered her.” Who the target of this accusation is and what his motive might be is strongly hinted at when the splendidly named Doctor Goldfinger (played by later director of considerable note, John Schlesinger, if you please) reveals that Daphne has died. “We did everything we could” is a stock assurance you’ll be hearing again from another medical professional a short while later. The distressed Mrs. Tucker then tells the sergeant that, “he’s on his way to America with that woman,” the man in question being Daphne’s husband, Sir Roderick Strood (Tom Conway), whom we soon learn is a music critic of some renown. That woman, meanwhile, is talented opera singer Elizabeth Anders (Eunice Gayson), and they are indeed on their way to America when Roderick is intercepted by Detective Sergeant Bolton (Russell Napier,) and informed that his wife has died. “I’ve…killed her,” the seemingly shocked Roderick mumbles. “It was those… tablets I gave her, they…” which he then counters by exclaiming anxiously, “But that’s impossible! It’s impossible!”

Cinematically speaking, things move quickly from here, and in the very next scene Roderick has been arrested and is being committed for trial at the Central Criminal Court for the murder of his wife. What happens then really caught me on the hop. Instead of sticking with Roderick, as expected, the film introduces us to seven of the twelve individuals who have been summoned to be members of the jury that will try his case, each of whom is given an introductory scene and most of whom are dealing with a family or relationship issue of their own. Will that become relevant? Given the effort put into this sidetrack from the main plot, it would be surprising if it didn’t. It’s then that we meet Roderick’s solicitor friend Mark (Hugh Latimer) and his barrister, Antony Harcombe Q.C. (David Horne), as Roderick tells them in flashback how events unfolded that led to what he claims was the accidental death of his wife. He reveals that as he’d been having trouble sleeping, Elizabeth had given him some of her prescription drugs to help him relax with the proviso that it would be dangerous to take more than two at a time. With Daphne in a state of agitated distress and the family doctor (Ronald Simpson) emphasising how important it is that she gets a good night’s sleep, Roderick elected to drop a couple of these tablets into her bedtime glass of milk, action that he claims she was aware that he had taken. Could that be the cause of her premature death?

Most of the remaining 40 minutes unfold as a courtroom drama in which we are shown snippets of testimony from the cooperative Elizabeth, from the venomously vindictive Mrs Tucker, from Roderick himself, and from Detective Sergeant Bolton, whom Harcombe is able to trip up on a matter of semantics that may or may not make a difference to the case. As the trial concludes, the film moves into the jury room, where single holdout Bonaker (Victor Maddern) makes his case with a conviction that has more than a whiff of Twelve Angry Men about it. Except Sidney Lumet’s masterpiece would not be released until the following year, and while the Reginald Rose teleplay on which it was based was first screened in 1954, the novel on which The Last Man to Hang was based – The Jury by Gerald Bullett – was published back in 1935. You can thank Kim Newman and Barry Forshaw on their commentary track for that useful snippet.

The Last Man to Hang was directed by Terence Fisher before his work for Hammer revealed that he had a real gift for cinematic horror. His direction here is solid enough, with only the occasional arrestingly expressively composed shot or use of lighting (kudos on this score to cinematographer Desmond Dickinson) giving a flavour of the style he would soon go on to demonstrate in spades. As a leading man, Tom Conway gets the job done but does lack the effortless suaveness of his more famous brother, George Sanders, while as Housekeeper Mrs. Tucker, Freda Jackson is so colourfully vindictive at times that I had to fight the urge to boo her in the courtroom scenes. As Elizabeth, Eunice Gayson is a class act whose courtroom testimony comes across as honest and grounded, and in the flashback scenes, Elizabeth Sellars is emotionally expressive as the increasingly jealous and volatile Daphne. David Horne is a bit of a scene stealer as Antony Harcombe Q.C., and I did rather like Walter Hudd’s low-key performance as the judge, who kicks against cliché by asking for clarification of points without coming across as a socially ignorant old duffer.

12 Angry Men or The Verdict it’s not, but The Last Man to Hang is still an engaging watch with solid performances and a handful of rather well written exchanges. Whether you buy into the late film twist is another matter entirely (Newman and Forshaw certainly didn’t), but the curious thing about it is that it’s arrival is signalled during the opening ten minutes, but we as viewers are effectively misdirected by the unfolding drama into forgetting what we witnessed and wondering how Roderick will get out of this mess.

WICKED AS THEY COME

Kathy Allen (Arlene Dahl) is fed up with her life as a New York factory worker and the cramped apartment she shares with her deadbeat stepfather, Frank (Sidney James), in which he and his sleazeball friends Chuck (Gilbert Winfield) and Willie (Patrick Allen) hang out and play cards. A regional beauty contest offering a trip to Europe as key part of its prize offers her a possible way out, and with competition fierce, she flirts with Mike (Marvin Kane), the son of local newspaper proprietor Sam (David Kossoff), who as well as organising the contest will be judging the result. To further increase her chances of bagging the prize, Kathy then elects to flirt with Sam as well. Once she wins the now rigged competition, she immediately casts both men aside and heads off to London, where she uses the fact that men are instantly attracted to her to climb the social ladder with the aim of turning her back forever on her poverty row past.

Wicked as They Come is, I would suggest, a film whose gender politics have dated rather better than surface impressions might seem to suggest. Armed with just that accusatory title and the above basic synopsis alone, you could be forgiven for expecting a film in which the central character is presented and portrayed as a cold-hearted and manipulative bitch, if you’ll forgive the use of that archaic insult. Add to this the fact that Kathy reacts with angry revulsion every time a man so much as touches her and we would seem to have the framework for a misogynistic tale in which a man-hating gold-digger takes ruthless advantage of a whole string of naively innocent men. Except it’s not that simple, not by a long shot. Sure, Kathy takes advantage of Mike’s very real affection for her, and uses charm and deception to convince Sam that she has genuine feelings for him before callously dumping them both once she wins the prize that she has conned them both into awarding her. But from the moment she boards a plane for Blighty, she becomes the target for almost every entitled male with money and position, all of whom objectify her and take her good looks as a licence to immediately start hitting on her. That she quickly learns to turn this around and put it to her advantage is not something I feel she should be negatively judged for, and indeed gives the character something of a feminist twist.

Unexpectedly, perhaps, Kathy is also quite prepared to put the work in when her efforts to flirt her way to the top hit a brick wall. When hot-headed Larry Buckham (Michael Goodliffe) falls in love with her after a single dinner date (which is lightning fast even by old-school movie standards), she deceives him into believing that the two will soon be married, then uses his credit with one of London’s top stores to buy expensive clothing and jewellery that she then pawns to raise the money she needs to enrol in a reputable secretarial school. Here she excels and graduates with a high enough recommendation to convince happily married managing director of Dowling International, Stephen Collins (Ralph Truman) to grant her a personal interview, only turning on the charm when he regretfully informs her that she lacks the required experience for the role for which she has applied. In no time at all, she’s working in Dowling’s outer office under the direction of his stuffily disapproving secretary, Miss Russell (Totti Truman Taylor), whose position you just know Kathy will eventually find some way to usurp.

The single male through-line in Kathy’s upward journey is Dowling media manager Tim O’Bannion (Phil Carey), who is the first to pester Kathy on her flight to London and who repeatedly pops up to chance his hand with her again or mock or criticise the lengths that she is prepared to go to in pursuit of her goal. At first, and frankly for a while after that, our Tim comes across as a self-satisfied dick (maybe that’s just me), but over the course of Kathy’s increasingly mercenary climb of the social ladder it becomes clear that his feelings for her run deeper than his initial grinny flirting might suggest. This is confirmed (spoilers ahead, hop to the next paragraph to avoid) when he pays her a drunken visit on the eve of her wedding to the middle-aged company boss John Dowling (Ralph Truman) and bitterly wonders out loud what happened to her in her youth to turn her into a cold-hearted woman incapable of love. It’s a question that he is later able to find his own answer to, one whose roots remain sadly all too relevant today but were rarely discussed in 1950s British cinema.

You could argue that Wicked as They Come earns its noir classification in the character of Kathy alone, who on the surface is an amoral femme fatale who uses her charms to seduce men for their money or position and leave them emotionally destroyed without her conscience taking the smallest hit. Indeed, it’s hard not to see a few parallels at least with Linda Fiorentino’s even more ruthless Bridget Gregory in John Dahl’s 1994 neo-noir gem, The Last Seduction. Even if you put this aside, however, the film delivers a final 20 minutes that is so soaked in noir – visually as well as tonally – that it would earn its genre badge on that alone, right up to and including a final scene that refuses to tidily tie up a key thread of the story, and which ends on a pleasingly ambiguous note.

The performances are solid, with Arlene Dahl shining brightest as Kathy, and direction from co-writer (with Robert Westerby and Sigmund Miller, from the novel Portrait in Smoke by Bill Ballinger) Ken Hughes – whose biggest hit came 12 years later with Chitty Chitty Bang Bang (1968) but who preferred to be remembered for his 1970 historical biopic Cromwell – is robust without ever calling attention to itself. That the film’s presentation of men of a certain social position (it’s worth noting that Kathy is never pestered by service work level males) and their entitled attitude to attractive women has not really dated over half a century later is a little grim, but is also a key reason why the film itself feels younger than its 1956 release date confirms that it is.

SPIN A DARK WEB

What is it with crime movies and boxing venues? Long before the underdog glory of Rocky (1976), if movie characters entered a boxing gym there was a good chance it would be in connection with a misdeed of some description, usually one involving violence or murder. Of course, this does have some real-world basis in the gangland connections that some of these clubs once had, and the two most infamous British gangsters of all, Ronnie and Reggie Kray, were keen amateur boxers. It’s also worth remembering, however, that many of these clubs were instrumental in providing troubled kids with an outlet for their frustrations and aggression and turning their lives around for the better. But Spin a Dark Web is a 1956 crime movie that opens in a London boxing gym, so you just know trouble is coming in one form or another.

As the film begins, boxing club owner Tom Walker (Joss Ambler) is advising his boxer son Bill (Peter Hammond) on how to win tonight’s title fight, an event that Bill’s sister Betty (Rona Anderson) is looking forward to attending. She had planned to go with her boyfriend, Canadian émigré Jim Bankley (Lee Patterson) – another aspiring boxer who is on good terms with Bill – but he disappoints her by cancelling because he’s chasing a job whose specifics he remains curiously vague about. When he arrives at the location he’s been directed to that evening, he’s told to get lost by the disinterested Sam (Sam Kydd), but when a large (and uncredited) goon is called to eject him, he quickly floors the man with two sharply delivered punches. His subsequent move to break a chair over the heads of both men is fortuitously halted by the appearance of Buddy (Robert Arden), a fellow Canadian with whom Jim has been friends since their army days. Buddy now works for Italian mobster Rico Francesi (Martin Benson), whom he approaches about getting Jim work with their firm. Initially dismissive, Rico is eventually persuaded to give him a go, less because of Buddy’s sales pitch than the casual interest that his sister Bella (Faith Domergue) has shown in this handsome young lad.

The next day, it turns out that Bill has ignored Rico’s orders to take a dive and won the title fight, losing Rico a substantial sum of money. He responds by having one of his boys, a young ruffian named McLeod (Bernard Fox), pay Bill a visit to remind him to do what Rico says. “This time,” Rico tells him, “no trouble, understand? Everything nice and quiet and polite, okay?” When McLeod confronts Tom at the gym, however, Tom claims to know nothing about their “little arrangement,” and when Bill walks in dressed in shorts and boxing gloves, he floors McLeod with a single punch, which McLeod responds to by jumping to his feet and violently coshing Bill on the back of his head. Later that day, Inspector Collis (Peter Burton) of Scotland Yard pays Rico a visit and reveals that Bill has died of his injuries, and that Tom has claimed that Rico was behind his murder. Unsurprisingly, Collis is keen to talk to McLeod, who is now on the run and whom Rico claims he fired months ago and has had nothing to do with since. Jim, meanwhile, has been seduced by Bella and knows nothing of Rico’s involvement in Bill’s murder, but his former skills as a talented telephone engineer soon see him being pulled further into Rico’s criminal plans.

Watching the films in the set in the listed order as I was, I knew before the first twenty minutes of Spin a Dark Web were up that this was going to be my favourite of the set so far, and it went on to live up to that initial impression. Smartly scripted by Ian Stuart Black from the novel Wide Boys Never Work by Robert Westerby, it’s well paced and structured by director Vernon Sewell (whose cult 1962 crime movie Strongroom is coming soon to Blu-ray from the BFI). It’s also the grittiest looking film of the collection, in part due to the need to shoot on high-speed stock to capture the vérité shots of Jim walking the neon-lit street of London at night, courtesy of cinematographer Basil Emmott, impressive, sometimes documentary-like night and daytime location work that helps keep the story grounded in reality.

Where the film really shines is in its characters and performers, none of whom overplay roles that could easily have come across as shallow archetypes. This is especially true of London-born actor Martin Benson, whose Italian accent as Rico is carefully judged, being clearly detectable but never exaggerated, just as you would imagine an Italian born man might speak after living in London for many years. Canadian Lee Patterson nicely underplays the role of Jim, being loose with his fists when physically confronted but politely and respectfully deferential to Rico, even when he starts openly dating his sister. Bernard Fox doesn’t have much screen time as McLeod, but when he pays that “it would be a shame if something happened” visit to Tom, there’s just a whiff of Chaz Devlin from Performance (Donald Cammell, Nicolas Roeg, 1970) about his portrayal, enough to make me wish we’d seen more of him in smarmily threatening mode. Best of all is Faith Domergue as Bella Francesi, a self-confident femme fatale who hovers meaningfully in the background when her brother is conversing and pursues Jim with the cool of someone slowly wearing down a business rival. She’s also pragmatically quick to suggest that the more reticent Rico should eliminate a problematic individual, and later it is more than hinted that she is the real power behind the criminal throne. Attractive, seductive and easy to fall for she may be, but as the title suggests, any man that flies willingly into her web does so at his peril.

THE LONG HAUL

After six years overseas in the American army moving from base to base with his British wife Connie (Gene Anderson) and young son Butch (Michael Wade), Corporal Harry Miller (Victor Mature) finally gets his hoped-for discharge papers and is eagerly anticipating returning to the US. Connie, however, is a lot less keen, and eventually convinces Harry to move the family back to her home city of Liverpool for a few months before moving on to America, assuring him that he can get a job driving trucks for a firm run by her uncle, George Mills (Wensley Pithey). The pay’s not great, but with his options limited, Harry takes the job, and is promptly shown how to cut his journey time by seasoned Irish driver Casey (Liam Redmond), whose lorry he follows on his first night out. After the two take a coffee break at a roadside transport café, Harry steps outside and sees two men stealing goods from Casey’s lorry and directly challenges them. A fight breaks out that leaves the thieves bruised but the late-arriving Casey frustrated. “Boy, you’ve got a lot to learn about this game,” he tells Harry and sends him on his way, then sheepishly hands back the bribe money he has been paid to the two deeply unhappy men. Their names, by the way, are Mutt and Jeff (Dervis Ward and Murray Kash), which is either a deliberate nod to Bud Fisher’s famous American comic strip of the same name, or a teeny bit of “oh, that’ll do” writing on the part of writer-director Ken Hughes or original novelist Mervyn Mills. Given the quality of the storytelling and character work here, I absolutely favour the former.

Harry delivers his cargo, then enters the local dispatch office in the hope of securing another consignment to make his journey back to Liverpool pay, but when Mutt and Jeff make an appearance and spot Harry waiting, they pop into the back office and have a few quiet words with the dispatcher, and as a result he is refused any further work. He reacts by entering the back office himself and taking his complaint to boss man Joe Easy (Patrick Allen), where he is once again manhandled by Mutt and Jeff, but this time is knocked out and tossed unceremoniously out back amongst the garbage cans (don’t blink, or you miss the fact that one of the men who carts Harry away is an uncredited Arthur Mullard). An ex-trucker himself, Joe is now the no-nonsense boss of a criminal firm with a legitimate front, one whose books are kept clean by accountant Frank (Peter Reynolds), whose glamorous sister Lynn (Diana Dors) Joe is dating. Neither Frank nor Lynn are exactly fans of Joe’s ruthlessly rough methods, and when the bored Lynn leaves the office to head for home, she stops to help the dazed and injured Harry and place him in the concerned Casey’s care.

The next evening, just as Harry is about to clock off after a long day’s work, he is approached by George and asked if he’ll take on a night run to transport a consignment of whisky to Glasgow. Tired through he is, Harry could use the extra money, and when he notes that this would normally be Casey’s run, George’s inexplicit response indicates that he’s become aware of Casey’s little arrangement with Joe. When Casey realises this has happened, he calls to warn Joe, who was just on his way out to dinner with Lynn. Frustrated at the thought of losing such a valuable shipment, Joe decides to sort it out himself and heads for the transport café at which the goods are normally offloaded from Casey’s lorry, at which (nice timing, Joe) Harry is taking a brief journey break. Joe offers Harry a deal to take the whisky off his hands, but Harry simply ignores him, and when the frustrated Lynn enters the café, she is humiliated by Joe and slaps him across the face in angry response. When she flees and Joe lunges forward to grab her, he is held back by Harry and tripped over by another trucker, whom the furious Joe immediately turns on to deliver a beating, allowing Harry to quietly exit the café unmolested. When he enters his cab, however, Lynn is in the passenger seat begging him to drive her away.

If you came to this set primarily for the noir, then you’ll find it in spades in The Long Haul, in the characters, in the “oh hell no” turns of the plot, in Harry’s moral decent into betrayal and criminality, in the later glimmer of possible partial redemption, and even in the expressionistic night-time lighting and framing of Basil Emmott’s deliciously moody cinematography. The setup once again provides a solid reason for the inclusion of an American star in the otherwise British production to help its overseas sales, and few actors could convey feelings of tortured doubt, despair and moral distaste like Victor Mature, who really gives it all as Harry in his steady fall from grace. Patrick Allen, meanwhile, makes for an imposingly ruthless and morally bankrupt gang boss, convincing completely as a one-time working man who has muscled his way to the top and dresses himself in the sheen of wealthy respectability. And then there’s Diana Doors, who as overdressed gangland moll Lynn gets to show her acting chops in a role that the above plot summary may make sound merely decorative but which proves to be an intriguing inversion of traditional femme fatale. Here, the beautiful woman – and dressed to the nines, Lynn is visually a blaze of white light in an otherwise dark world – is not looking to seduce the previously upright male lead for personal gain and ends up doing so more out of loneliness and a desire to escape a life that has become an emotional prison, one whose once attractive material rewards have long since lost their sheen.

Writer-director Ken Hughes, who did a solid job on Wicked as They Come, feels even more at home with the tonally darker and tougher material here, later shifting the noir into overcast daylight for a tense 22-minutes sequence that riffs on Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 The Wages of Fear [Le Salaire de la peur]. Seriously impressed though I was with Spin a Dark Web, for me The Long Haul was the best film yet in this collection, and one whose noir classification is more than deserved. One more to go…

FORTUNE IS A WOMAN

If the connection between boxing gyms and crime in movies was informed by a degree of historical fact, the notion of an insurance investigator as a gateway to noir was stamped in platinum back in1944 with Fred MacMurray’s Walter Neff in Billy Wilder’s noir par excellence, Double Indemnity. Here, the location has been switched from Los Angeles to London and the insurance investigator in question is the very English Oliver Branwell (Jack Hawkins), who as the film begins awakes from a nightmare whose gothic surrealism sees the sequence play like the opening of a haunted house horror movie.

It’s Christmas Eve, but work at loss adjusters Abercrombie and Son doesn’t let up for the holiday, and Oliver is sent to Lowis Manor to assess the damage caused by a fire. That he fails to register that the mansion in question appears to be the one from his nightmare is little odd, but we’ll let that one slide. When he arrives, he is met by the owner, Tracey Moreton (Dennis Price), and his cousin, Clive Fisher (Ian Hunter), but it’s when Oliver locks eyes with Tracey’s attractive wife Sarah (Arlene Dahl) that his interest really piques. Indeed, it’s seemingly the chance to spend more time in her company that prompts Oliver to accept Tracey’s invitation to stay to dinner, which is also attended by Tracey’s brusque elderly mother (Violet Farebrother). Oliver clearly fancies Sarah, which is a bit much given that he’s only just met her and her husband is right there and seems like a nice guy, and Sarah never seems comfortable in Oliver’s presence. A few days later, after repeatedly phoning her workplace and getting no answer, Oliver accosts her in the street and invites her for coffee. Once again uncomfortable at this attention, she initially makes excuses then smilingly agrees, and it’s then that we find out that the reason Oliver was so fixated on her at the house was because some years earlier he and Sarah were dating and lost contact immediately after they broke up.

On the basis of Oliver’s assessment, the insurance company pays for the damage to Tracey’s house and to some valuable paintings, but a few months later, another case leads Oliver to suspect that the claimed damage may not all be above board. Sent to look into a claim made by Charles Highbury (why, it’s Welsh-accented Christopher Lee!), aka ‘The Singing Miner’, Oliver’s investigation into the true cause of the black eye that Charles is sporting leads him to the apartment of attractive and flirty Vere Litchen (a delightfully playful Greta Gynt), on whose wall sits one of the very paintings that Tracey claimed was damaged in the fire. It’s also the one that appears in his nightmare, but once again, that doesn’t appear to register. Keen to get to the bottom of what he now suspects was insurance fraud, Oliver consults an expert on how to differentiate a forged painting from the real thing, and one night when he is sure that the building will be unoccupied, he travels to Lowis Manor, quietly breaks in, and locates the paintings that the insurance company paid out to have restored, and this is where the film moves into a different gear entirely. I’m not about to reveal what happens next, know just that it makes good and then some on the gothic horror vibes of that opening dream sequence, plunging Oliver into a noir-soaked waking nightmare in which a startling discovery leads to spectacular near catastrophe, one whose gloriously non-CG realism made me genuinely fear for Jack Hawkins’ safety.

Without getting into plot-spoiling specifics, things really complicate for Oliver from this point onwards, as he finds himself potentially incriminated in a serious crime and has to start engaging in the sort of deception that is part of his job as an insurance investigator to expose. The problem is that just about every decision he makes, including his efforts to uncover what is actually going on, seem to tie him up in even more convoluted knots. It certainly doesn’t help that the situation is being investigated by polite but the doggedly determined Sergeant Barnes (Michael Goodliffe) and Detective Constable Watson (Martin Lane), or that Oliver is being blackmailed by persons unknown, whose go-between is an almost archetypal dorky individual named Mr. Jerome (Bernard Miles).

It’s all splendid stuff, with Jack Hawkins inspired casting as Oliver, his gift for anxiety tinged delivery really coming into its own during the increasingly tense later stages. He’s well matched at every turn by a consistently strong supporting cast, with standout turns from Arlene Dahl as Sarah Moreton, Michael Goodliffe as Sergeant Barnes, and especially Greta Gynt as Vere Litchen, and watch out for favourite character actor George A. Cooper in a small role as a hotel porter. Full marks also to cinematographer Gerald Gibbs, whose lighting camerawork really comes into its own in that superb centrepiece sequence in the darkened manor, and to director Sidney Gilliat, who co-authored the screenplay with his long-term writing partner Frank Launder (with Val Valentine credited for adaptation) from the novel of the same name by Winston Graham, the pair having already made their mark back in 1938 with their tight and witty screenplay for Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes. Here they fashion a smartly structured noir that kept me guessing about how and even if the situation would be resolved right up to the final reveal, and whether the explanation that comes lives up to expectations that you may have built by now will be a subjective call. Either way, the ride to the finale is a tight, well performed and consistently gripping watch whose centrepiece scene may well be the highlight of this fascinating set.

Columbia Noir #7: Made in Britain

A Prize of Gold

UK 1955 | 98 mins

directed by: Mark Robson

written by: Robert Buckner, John Paxton; from the novel by Max Catto

cast: Richard Widmark, Mai Zetterling, Nigel Patrick, George Cole, Donald Wolfit

The Last Man to Hang

UK 1956 | 75 mins

directed by: Terence Fisher

written by: Ivor Montagu, Max Trell; Gerald Bullett, Maurice Elvey (adaptation); from the novel The Jury by Gerald Bullett

cast: Tom Conway, Elizabeth Sellars, Eunice Gayson, Freda Jackson, David Horne, Raymond Huntley

Wicked as They Come

UK 1957 | 94 mins

directed by: Ken Hughes

written by: Ken Hughes; Robert Westerby, Sigmund Miller (screen story); from the novel Portrait in Smoke by Bill Ballinger

cast: Arlene Dahl, Phil Carey, Herbert Marshall, Michael Goodliffe, Ralph Truman, Sidney James

Spin a Dark Web

UK 1956 | 76 mins

directed by: Vernon Sewell

written by: Ian Stuart Black; from the novel Wide Boys Never Work by Robert Westerby

cast: Faith Domergue, Lee Patterson, Rona Anderson, Martin Benson, Robert Arden, Joss Ambler

The Long Haul

UK / USA 1957 | 100 mins

directed by: Ken Hughes

written by: Ken Hughes; from the novel by Mervyn Mills

cast: Victor Mature, Diana Dors, Patrick Allen, Gene Anderson, Peter Reynolds

Fortune is a Woman [aka She Played with Fire]

UK / USA 1957 | 95 mins

directed by: Sidney Gilliat

written by: Sidney Gilliat, Frank Launder; Val Valentine (adapted by); from the novel Fortune is a Woman by Winston Graham

cast: Jack Hawkins, Arlene Dahl, Dennis Price, Violet Farebrother, Ian Hunter

distributor: Indicator

release date: 15 December 2025